“When it comes to transportation many people assume that you have to be in a wheelchair or have a visual handicap to need help. But you can look at the outside and not know what’s inside.” — Kheir Clinic patient

What can urban health centers from Los Angeles learn from a rural medical clinic in Sebastopol about solving transportation insecurity?

A lot, it turns out, including how important it is to meet patients where they’re at. Despite differences in clinic size, geographic scope, transit options, cultural backgrounds, and languages spoken between city and country clientele, they all face a similar challenge: how to help patients with transportation obstacles get to their medical appointments, a problem that health clinics around the country struggle to resolve at great expense to patient health, staff resources, and clinic funding.

In January, four clinics from the greater Los Angeles area — Clinica Romero, Kheir Clinic, Planned Parenthood Pasadena and San Gabriel Valley, and T.H.E. Health and Wellness Centers — were invited to small-town Sebastopol for a site visit to explore potential solutions to patients’ transportation challenges. The L.A. clinics are part of an 18-month learning community called Moving Clinics Upstream, a CCI program funded by Cedars-Sinai. Moving Clinics Upstream is designed to address top patient health concerns, specifically transportation and food insecurity, by going beyond the walls of the health center to assess these complex hurdles to providing health care for the communities they serve.

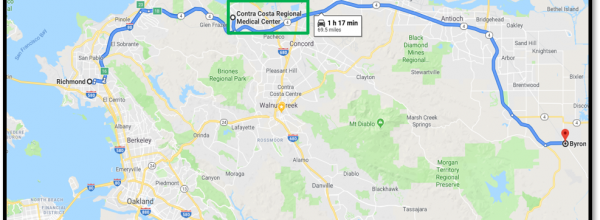

The L.A. clinics came to learn more about West County Health Centers (WCHC) in western Sonoma County, California, which serves as a model in this arena. As a part of its solution to a lack of reliable transit and gaps in non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT) coverage for Medicaid patients, WCHC teamed up with the tech startup Hitch Health. (Read our case study on WCHC to learn more.)

What Transportation Insecurity Looks Like

Western Sonoma County dwellers and Los Angeles residents aren’t alone in their transit woes. Many Americans lack access to affordable, accessible, and reliable transportation, and research has shown that this can be a significant obstacle to receiving health care, particularly for low-income patients. Medical transportation is the leading cause of patient no shows, according to a 2017 report from the American Hospital Association. Every year an estimated 3.6 million Americans miss getting medical care because of lack of transportation, according to one study. Missed appointments can lead to more severe and expensive medical conditions. Transportation barriers may mean the difference between worse clinical outcomes that could trigger more emergency department visits and timely care that can lead to improved outcomes, according to a study in the Journal of Community Health.

Missed appointments are also a drain on clinic resources. Figuring out transport can consume front office and medical staff time, as can following up with patients about missed appointments and no shows. It’s also costly: Missed medical appointments in the United States result in a staggering $150 billion in lost clinic revenue and staff time every year, according to one national estimate from a healthcare solutions IT provider.

As the January 2020 meet-up revealed, the reasons patients lack access to reliable transportation vary widely. Economics certainly play a factor for this population, but so are feelings of anxiety around driving (especially in a place like L.A., where navigating freeways and serious traffic is an issue and not just for nervous drivers). Some patients express discomfort over getting into a ride share with a stranger, citing safety issues, language concerns, or cultural considerations. Negotiating public transportation has its own set of concerns: some patients experience it as inconvenient, unreliable, and time-consuming at best, or intimidating, unhygienic, and unsafe at worse.

“In some cultures, it’s not acceptable for women and children to be transported by men they don’t know,” says Don Garcia, clínica monseñor (medical director) at Clinica Romero, a federally qualified community health center which serves a mostly Central American community of immigrants, refugees, political asylees, indigenous people, and other marginalized members of the community. The clinic, which has two locations, sees about 12,000 patients a year and offers medical, dental, vision, and behavioral care. “Some patients have a sense of insecurity around public transport because of language differences or legal status, others may feel claustrophobic and anxious in underground transit because of past trauma, anxiety, or security risk,” says Garcia. “These concerns are very real and present for our patient population, and we need to be sensitive to the circumstances that may prevent them from coming to our clinic or getting there on time. It’s about respecting patient dignity and meeting their needs.”

“In some cultures, it’s not acceptable for women and children to be transported by men they don’t know,” says Don Garcia, clínica monseñor (medical director) at Clinica Romero, a federally qualified community health center which serves a mostly Central American community of immigrants, refugees, political asylees, indigenous people, and other marginalized members of the community. The clinic, which has two locations, sees about 12,000 patients a year and offers medical, dental, vision, and behavioral care. “Some patients have a sense of insecurity around public transport because of language differences or legal status, others may feel claustrophobic and anxious in underground transit because of past trauma, anxiety, or security risk,” says Garcia. “These concerns are very real and present for our patient population, and we need to be sensitive to the circumstances that may prevent them from coming to our clinic or getting there on time. It’s about respecting patient dignity and meeting their needs.”

In addition, many patients lack access to a vehicle or a family member or friend who can drive them. Bus service can be spotty with long wait and travel times, and require navigating above- and below-ground transit transfers, which can be a hardship for vulnerable patients, including the physically and mentally impaired and those who don’t understand or speak English. For very low-income patients, bus fare and gas money may prove prohibitive. Most public transit riders in Los Angeles are low-income residents of color. A quarter of the region’s public transit trips are made by fewer than 3 percent of residents, many of whom have no access to a car, according to Los Angeles Times transportation writer Laura J. Nelson. And while the county is working to improve public transportation for all, the area remains car-centric and traffic congested, with an inclusive public transportation system decades away from being a reality.

Applying Design Thinking

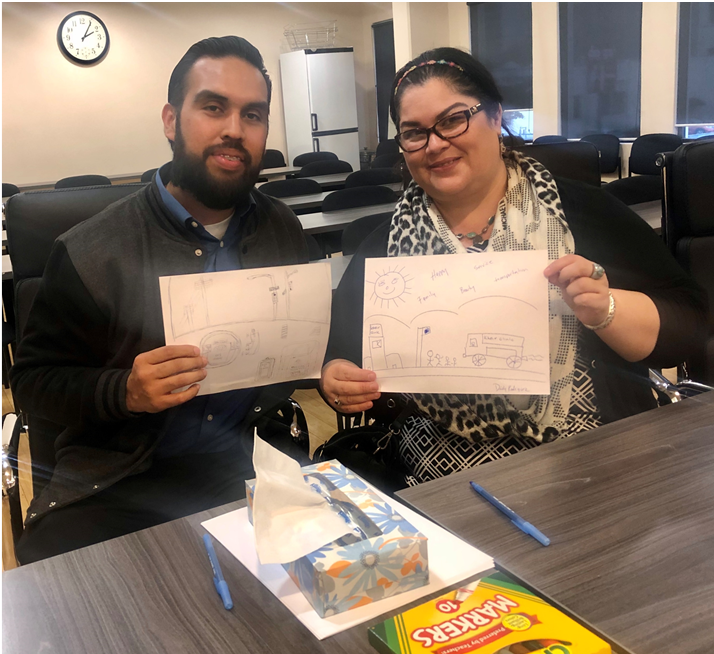

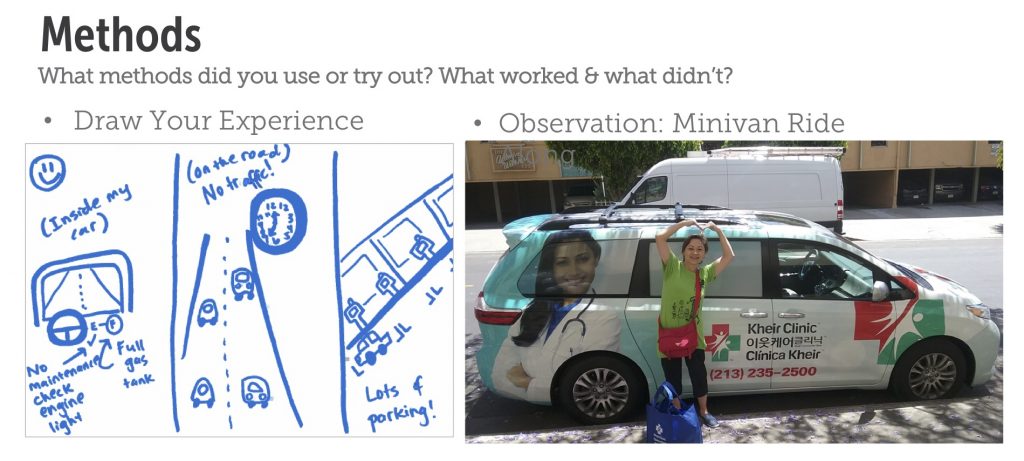

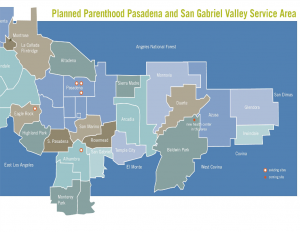

To get a handle on how transportation insecurity is impacting their clinics from their patients’ perspectives, Moving Clinics Upstream taught the Los Angeles clinics how to utilize “design thinking” techniques such as open-ended interviews, draw your own experience exercises, and observation activities. This human-centered design approach to problem solving is collaborative, creative, and begins by understanding people’s needs and experiences. For instance, in addition to paper surveys on transportation, clinicians at Planned Parenthood Pasadena and San Gabriel Valley’s Eagle Rock clinic have begun asking patients how they arrived at their well-person appointments, as part of an open-ended dialogue to try to more accurately tease out transportation insecurity among its clientele.

To get a handle on how transportation insecurity is impacting their clinics from their patients’ perspectives, Moving Clinics Upstream taught the Los Angeles clinics how to utilize “design thinking” techniques such as open-ended interviews, draw your own experience exercises, and observation activities. This human-centered design approach to problem solving is collaborative, creative, and begins by understanding people’s needs and experiences. For instance, in addition to paper surveys on transportation, clinicians at Planned Parenthood Pasadena and San Gabriel Valley’s Eagle Rock clinic have begun asking patients how they arrived at their well-person appointments, as part of an open-ended dialogue to try to more accurately tease out transportation insecurity among its clientele.

The end goal is to find solutions to reduce missed appointments and no shows; but right now, these clinics are reaching out to patients to understand both the scale and scope of the problem. Low-income patients facing transportation challenges are often dealing with other stressful problems such as food, housing, employment, immigration, and financial insecurity. By meeting their transit needs to getting to their medical appointments, patients express gratitude for having “one less thing to worry about.”

Said one Kheir Clinic patient: “Having transportation improves my mental stability, my physical condition, and helps me feel normal again.” Added another: “We need a GPS in all aspects of our lives.”

Meeting Patients Where They’re At: Culturally-Sensitive Care

Participants in Moving Clinics Upstream aren’t starting from scratch. In fact, the program is an opportunity to build on their previous efforts and better evaluate how to meet patient needs.

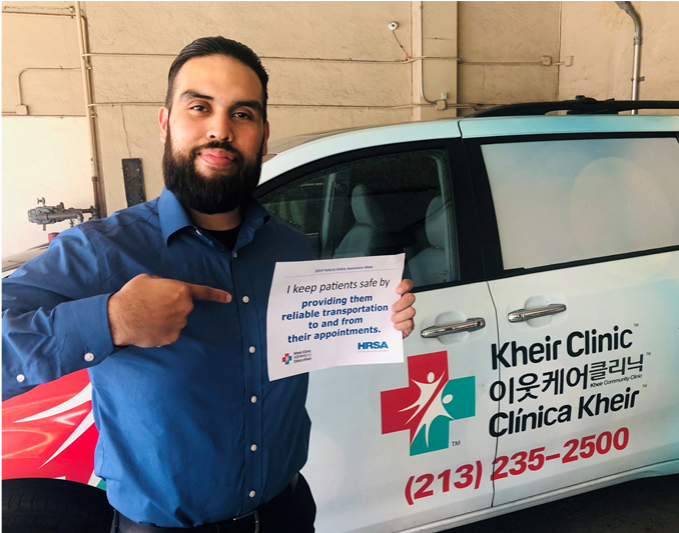

Kheir Clinic in Los Angeles’ Koreatown currently uses an internal van service and employs a driver to transport some of their most fragile patients, including seniors, those with language barriers, and patients with vulnerable legal status. Kheir Clinic’s four medical sites serve a predominantly Korean population, as well as native Spanish, Thai, and Bengali speakers. The clinic sees around 13,000 patients a year for a total of more than 60,000 visits. The van service, provided by transportation coordinator Nelson Guevara, has proven a valuable resource and provides a level of attention, compassion, comfort, and safety that clinic patients appreciate, says Floribel Diaz, former patient services supervisor at the clinic. They feel cared for, listened to, seen. And they show up for their appointments. “It’s not just a van and it’s not just a driver,” one patient told the Kheir team. “He [Guevara] makes sure I am safe and he makes sure my needs are met.” In 2019, 959 patients utilized the van service and there were less than a handful of no shows for pick-ups.

Kheir Clinic in Los Angeles’ Koreatown currently uses an internal van service and employs a driver to transport some of their most fragile patients, including seniors, those with language barriers, and patients with vulnerable legal status. Kheir Clinic’s four medical sites serve a predominantly Korean population, as well as native Spanish, Thai, and Bengali speakers. The clinic sees around 13,000 patients a year for a total of more than 60,000 visits. The van service, provided by transportation coordinator Nelson Guevara, has proven a valuable resource and provides a level of attention, compassion, comfort, and safety that clinic patients appreciate, says Floribel Diaz, former patient services supervisor at the clinic. They feel cared for, listened to, seen. And they show up for their appointments. “It’s not just a van and it’s not just a driver,” one patient told the Kheir team. “He [Guevara] makes sure I am safe and he makes sure my needs are met.” In 2019, 959 patients utilized the van service and there were less than a handful of no shows for pick-ups.

That sentiment was mirrored in an observation conducted by Diaz in a ride-along: Guevara, noted Diaz, is patient, waits for riders, gets out of the van to greet patients, and helps physically impaired patients get into the van, which they are receptive to and grateful for. It’s clear, says Diaz, that patients, especially repeat riders, have a relationship with Guevara, and view the service as part of clinic care.

The observation was echoed by staff from other Moving Clinics Upstream clinics dealing with transportation insecurity in their patient population. Typically transit concerns impact the neediest of patients, who often frequent a clinic on a regular basis and require a high level of touch and individual attention. For a host of cultural, language, and behavioral reasons, many patients prefer the security of the same van and same driver for appointments.

“A lot of our patients look to front office or call center clinic staff—who may come from the same culture and speak the same language—for support around solving their transportation problems,” says Julio Reyes, a patient services representative at T.H.E. “They look to us for emotional support and a warm handoff.”

One Size Doesn’t Fit All

Moving Clinics Upstream participants appreciate that there is no one proven package or change map to address patients’ social needs. And what might be a good fit for one clinic may not work at another. At this stage of the process, each of the four clinics are in deep research and investigation mode to better understand the extent of transportation insecurity among its population and the reasons why it exists.

In the past, T.H.E. Health and Wellness Center in Los Angeles has offered its patients with transportation challenges the opportunity to use an external van service, which served about 2,500 patients annually. Currently the clinic funds an internal driver and pays for a minivan, which can transport four patients at a time.

In the past, T.H.E. Health and Wellness Center in Los Angeles has offered its patients with transportation challenges the opportunity to use an external van service, which served about 2,500 patients annually. Currently the clinic funds an internal driver and pays for a minivan, which can transport four patients at a time.

T.H.E. has also provided patients public transit tokens in the past, as part of a service for poor Angelenos known as the Low Income Fare is Easy Program (or LIFE). The clinic distributed around 220 free bus tokens each month. The Los Angeles County Metro has since transitioned from tokens to TAP cards, which T.H.E. is in the process of purchasing to begin distributing to patients soon. The clinic is currently figuring out how to help patients navigate the tap card application process. Ideas include having the clinic’s promotoras (community health workers) assist patients with these applications.

Now T.H.E. is exploring a telehealth alternative for patients requiring follow-up or advice that doesn’t require a visit so they can receive care without transportation. This pilot project could alleviate access barriers for patients who are comfortable using technology. Telemedicine —delivering care at a distance — is a rapidly growing service in health care.

So is Planned Parenthood Pasadena. “We are in the beginning phase of launching a telehealth program and we’re really excited about this because we’re seeing this as a way to directly impact transportation as a barrier to health by meeting patients where they are,” says Ashley Leonard, Planned Parenthood Pasadena’s health centers systems manager. “Giving them easy, safe, compassionate access to one of our providers without having to leave the comfort of their homes or wherever they choose to have that telehealth visit.”

A Ridesharing Surge

In recent years, rideshare companies have become a sought-after vehicle to solve patient transit woes for Medicaid recipients and others in need of a ride to their doctor. Like WCHC, the LA clinics are exploring these services and technologies.

At the Planned Parenthood clinic, Uber Health and a company Lyft account, plus L.A. Metro TAP cards, are options for patients in need of transit assistance.

Clinica Romero has begun using Uber Health for its patients with diabetes and are tracking whether it helps with attendance and compliance. It is also analyzing data from a survey of 200 patients about their transportation challenges. And it has purchased a van and is consulting with the Kheir Clinic and others on best practices for its use.

Currently, T.H.E., which has five clinics and a mobile site and serves a mostly African American and Latinx population in South Los Angeles, relies on Uber Health to ensure transportation insecure patients are able to get to and from clinic. The ride share service, funded out of the clinic’s general operating budget, serves around 500 patients (out of the 15,000 patients it sees each year) for an estimated average round trip of $10. The clinic’s goal is to double the number of rides offered through Uber Health, and ensure transportation is available to all patients at every site.

Kheir Clinic uses Uber, not Uber Health, to transport some of its patients. Since Uber Health requires patients to order and coordinate the ride themselves, and the vast majority of their clientele are best served in a language other than English, it’s more efficient for clinic staff to order rides for patients, explains Kirby Rock, director of external affairs at Kheir Clinic. The clinic also provided free bus tokens from 2011 through 2019, until LA Metro phased them out in November. The clinic is in the process of identifying an alternative way to provide public transportation subsidies for patients and is also exploring telehealth options.

It takes work to match tech, transport, and the transport insecure. “A lot of our patients speak Spanish and are not tech savvy,” says Julio Reyes, a patient services representative at T.H.E. That means Reyes is often helping patients with their transit needs. At the WCHC site visit discussion, Reyes also learned that other clinics have patients that tend to return frequently to the clinics, not just because of medical needs, but because the clinic is a place where vulnerable people feel safe and receive personal attention. The front desk staff — often the first point of contact with patients — play an important role in helping resolve patient transportation needs, Reyes notes.

The clinic is interested in exploring whether Hitch Health might be a good fit for its patients and also whether or not it’s financially viable. “Our patients are open to learning how to use new tools, and if we choose to use Hitch Health, it is T.H.E.’s responsibility to educate and train them on how to use the tool,” says Cheryl Trinidad, T.H.E.’s chief development and communications officer.

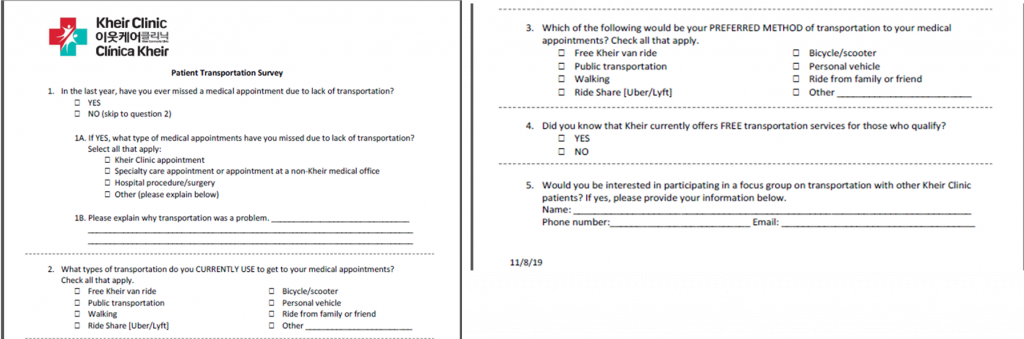

‘We Missed You at Your Appointment’

Just how widespread transportation insecurity is among these clinics’ patient population remains unclear. For instance, through a recent patient transportation security questionnaire, the Kheir Clinic learned that less than 10 percent of patients identified as transportation insecure. But that figure is likely low because of an unintended bias in the study, says Diaz, which surveyed only patients who actually made it to their clinic appointments. The clinic used traditional paper surveys at the time of appointment arrival or before departure. They also used tablets installed with electronic surveys and a texting program provided by WELL Health that allows the clinic to communicate with patients remotely through SMS messages. Primarily used for appointment reminders, the software also supports responses to simple survey questions. Questionnaires were available across all delivery methods for English, Korean, and Spanish speakers, and in written form for Bengali and Thai-speaking patients.

Currently, Kheir Clinic and other Moving Clinics Upstream participants are exploring avenues—including follow-up phone calls by call center staff or text messages—to reach the patient population that don’t always make it to the clinic door to get a better handle on the scope of the problem.

Perhaps most surprising of all: 76 percent of patients were not aware of the Kheir Clinic van service. That’s an opportunity to do better outreach around the program, says Diaz, and something the team will also address when they convene a 20-patient focus group on transportation insecurity. The service is promoted during all new patient enrollment and orientation sessions with patient resources department specialists, which is where the majority of users are identified. Clinic staff also refer patients who are in need. The clinic is considering targeted flyers and more social media posts on the service, which can accommodate around 15 to 20 round-trip rides a day, serving around 10 patients. The clinic provides a maximum of 10 to 15 Uber rides a day as well.

“Often times our patients encounter difficulty scheduling rides for specialty appointments and do not arrive on time to their visit and are turned away,” says Diaz. “We have to understand several cultural and linguistic components to help our patients whose first language is not English.” As with follow up, the clinic is sensitive to how it communicates with patients. Rather than asking: “Why didn’t you show up for your scheduled appointment?” which can seem blaming or shaming, language is couched in less punitive terms: “We haven’t seen you in the last year.” Similarly, a text message to a patient might read: “We missed you at your appointment versus you missed your appointment.”

In 2019, Kheir Clinic had around a 15 percent no-show rate for clinical appointments; that’s an estimated $1.5 million in lost revenue based on the average reimbursement rate for a clinic visit, according to Kirby Rock, director of external affairs at Kheir Clinic.

Next steps for these clinics, which will take place during 2020, include conducting patient focus groups, analyzing survey data, and testing and implementing transit ideas based on patient input. Diaz says her clinic wants to be able to look deeper into what prevents patients from making it to their scheduled appointments. “Unless we drill down to the heart of the issue then we are not doing justice to our patients.”