Fighting a Pandemic and a War on Hunger at the Same Time

In the spring of 2020, a food pantry seemed like the most immediate response necessary to widespread food insecurity fueled by the pandemic and a dramatic increase in job loss, according to Los Angeles LGBT Center health services staff. “Making sure our clients had access to food became a top priority,” explains Linda Santiman, manager of integrated care at the center. “We knew we needed to figure out a system to serve people in need for as long as needed.”

Los Angeles LGBT Center is one of six, federally-funded Los Angeles clinics — including Altamed Health Services Corporation (in partnership with Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles), APLA Health, Behavioral Health Services, Eisner Health, and St. John’s Well Child & Family Center — who are part of an 18-month learning community called Moving Clinics Upstream, a CCI program funded by Cedars-Sinai. Moving Clinics Upstream participants focus on addressing food insecurity and transportation insecurity by fast tracking innovations that might serve as solutions to these intractable challenges.

One example: the center’s Pride Pantry, whose tagline is “we meet scarcity with abundance.”

Founded in 1969, the center provides a multitude of services for the LGBTQ community, including medical care, mental health counseling, affordable housing, homeless shelters, legal advice, advocacy, employment services, cultural events, and even a charter high school. According to the center, it is one of the few Federally Qualified Health Centers with providers who specialize in primary care for gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people and people living with HIV. With almost 800 employees and a budget of nearly $140 million, the center’s nine locations across Los Angeles—including the Trans Wellness Center in Koreatown—offer more services to more LGBTQ people than any other organization in the world. The center serves an economically and ethnically diverse population with about 50,000 client visits a month. Interwoven with these initiatives is a food focus that includes food services for seniors, meals for homeless youth, and an innovative, intergenerational culinary arts training program. Pre-coronavirus, the center provided more than 74,000 meals a year, according to Eater LA.

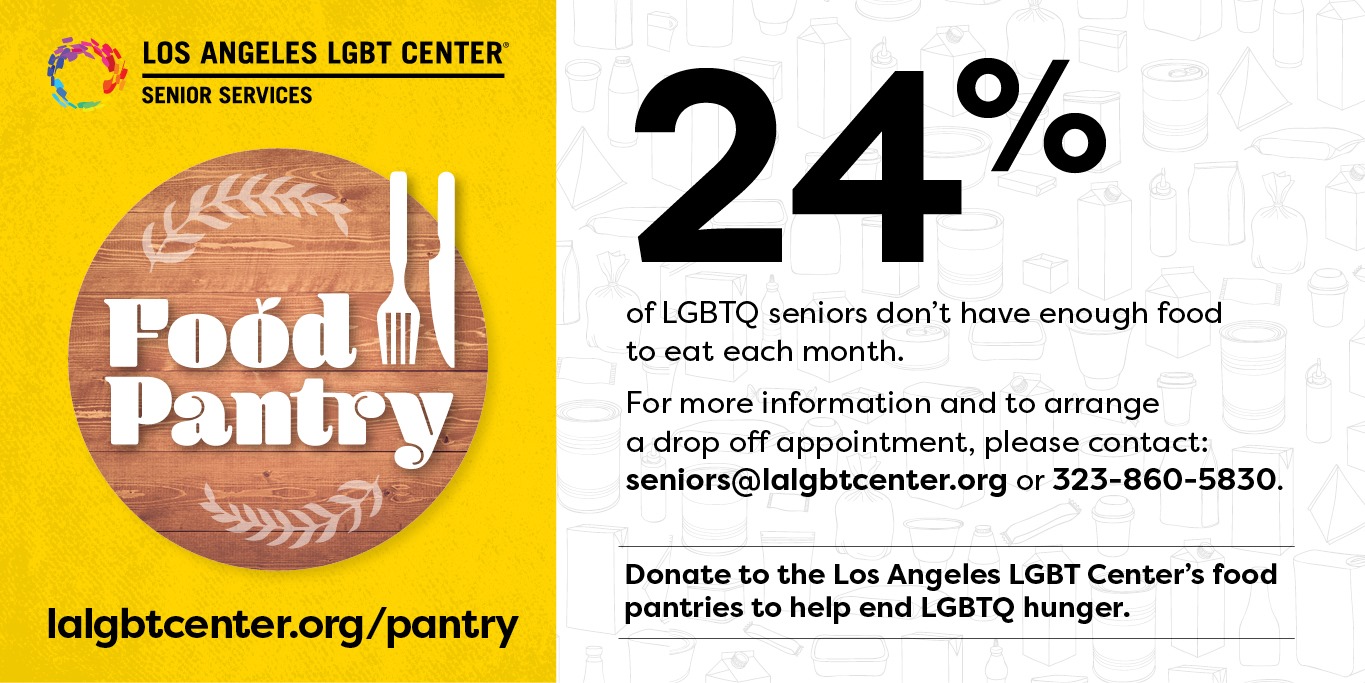

Food insecurity disproportionately impacts vulnerable populations, including low-income people, Black and Latino residents, seniors, young families, and members of the LGBT community. National research reveals that food insecurity among LGBT adults is almost double that of food insecurity among non-LGBT adults. Further, LGBT folks aged 18 to 44 are 1.3 times more likely to receive food assistance benefits (known nationally as the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program or SNAP and in California as CalFresh, and formerly known as food stamps) than heterosexual adults. Same-sex couples are 1.7 times more likely than different-sex couples to use food stamps and LGBT couples aged 18 to 44 who have children are 1.8 times more likely to receive SNAP than heterosexual couples with kids. Further, LGBT adults of color are twice as likely as their Anglo counterparts to experience hunger, according to data compiled by UCLA’s Williams Institute.

The combination of COVID-19 and widespread unemployment in 2020 resulted in hunger impacting many Angelenos — and not just low-income residents. More than one in four Los Angeles County households experienced at least one instance of food insecurity — a lack of access to affordable and nutritious food — between April and July 2020, according to a study by the University of Southern California Dornsife’s Public Exchange. The research also found that the pandemic overwhelmingly impacted women, people with low incomes and the unemployed, and Latino residents. “We’re getting a comprehensive look at how the pandemic has impacted the ability of Los Angeles County residents to afford food,” noted Kayla de la Haye, lead researcher on the study and assistant professor of preventive medicine at Keck School of Medicine of USC. “The spread of COVID-19 has worsened the already high levels of food insecurity among low-income households and marginalized groups and has even impacted demographic groups that are historically less likely to ever experience it.”

One doesn’t have to look far to find other evidence of the escalation in food insecurity. The Los Angeles Regional Food Bank reported a 145 percent increase in food distributed in 2020, compared with 2019. The LA County Department of Social Services reported a 179 percent increase in applications for CalFresh, during the height of the pandemic, according to the Los Angeles Times. Given this dire need in the county, safety net clinics are urgently exploring and experimenting with ways to make sure that their clients have enough food on the table.

“Pride Pantry has been very successful in the sense that we have been able to provide an additional, much-needed service to our clients during a pandemic,” notes Valenzuela, who says the service will continue while the demand for the resource remains.

For Valenzuela, a home cook with culinary training who says she comes from a culture where the heart of the family is in the kitchen, it’s not just a question of meeting her professional responsibilities. “It is an honor managing the pantry. I take great care and pride in the food I order. I make sure every box contains animal and plant proteins, soup, breakfast items, canned vegetables and beans, healthy snacks and drinks,” she notes, adding that around 90 percent of the pantry’s produce can be consumed raw or requires minimal cooking. “I am of the mindset every week that what we are distributing could be a client’s only source of groceries. It’s important to me that what our clients receive is a well-rounded distribution of food items that have variety and are nutritious.”

Food Insecurity Impacts All Generations

At the Los Angeles LGBT Center, which favors a patient-focused approach to addressing food insecurity, the food pantry has proven popular — and necessary — with clients of all ages. Long-time client Nathan, 35, has struggled with type 1 diabetes since childhood. In the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, Nathan, who lives in Hollywood, ended up in the emergency department when his blood sugar skyrocketed and he needed immediate medical help to control his condition. He left the hospital with his glucose in check and a $10,000 bill he couldn’t afford to pay.

Nathan reached out to the organization to educate himself about eating well on a budget and how diet can help manage his diabetes. “After talking to a nutritionist, I had confidence and felt more relaxed about my health,” says Nathan, who received a $150 grocery gift voucher and assistance with shopping as an incentive to meeting with the center’s dietician. “I went shopping with the food voucher and got high-quality food,” says Nathan. “I was amazed how my cabinets and refrigerator were full and how long it lasted. I’ve learned what is good for my diabetes and can now afford foods that benefit my health,” he adds. “After 17 years of poor-quality food, my health has finally turned around,” explains Nathan, noting that his A1C reading, a measurement of blood sugar control, has dropped two points since he made changes to his diet with the help of the center.

Morgan, another young, long-time client, echoes Nathan’s experience. He credits the food programs at the Los Angeles LGBT Center for transforming his health for the better. “For years I’ve eaten food that I couldn’t control but was all I could afford,” explains the 29-year-old from Van Nuys, who suffers from migraines, bipolar disorder, and the genetic disease Ehler-Danlos, which impacts digestion.

Morgan worked with the center’s dietician to figure out what foods he could afford. In addition to choosing nutrition-dense foods, he has cut gluten from his diet and credits these dietary changes for helping him improve his physical stability and mental health, which in turn allows him to manage his genetic disorder.

Morgan also received gift vouchers for attending an appointment with the center’s dietician, Carla Duran. Pre-COVID-19, clients could qualify for vouchers by attending in-person group nutrition classes as well. “During these classes and appointments, clients learn ways to develop healthier eating habits and receive nutritional guidance,” explains center staff social worker Jeff Garcia, who has also connected clients to the Pride Pantry. “It has been fulfilling to see the difference these services have made in our clients lives,” says Garcia. “Receiving food assistance has made our clients feel safe and supported during these difficult times.”

A Multi-Pronged Approach to a Complex Problem

Clients who are food insecure frequently have challenges meeting other basic needs — such as paying rent.

Housing costs are a huge financial burden for many food insecure clients, as the Los Angeles LGBT Center’s Brittany Hicks, who works as a housing stabilizer in the center’s housing for health program, knows only too well. “When the COVID-19 pandemic first hit I had serious concerns about my clients’ ability to access food. Many were unable to acquire or maintain a steady supply of food,” she explains.

But the center pivoted to meet this demand in a multi-pronged approach to tackle this complex problem. It has been able to help bridge these gaps for clients through key partnerships and funding support. For example, in April and May 2020, the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services (DHS) contracted with the global charitable feeding program World Central Kitchen to make pre-cooked meals available to vulnerable clients that center staff delivered to clients’ doors. “I have felt extremely grateful and appreciative to see my clients connected with the food services they desperately needed,” says Hicks. “As an active partner in the DHS/World Central Kitchen meal delivery I was afforded the opportunity to witness the direct relief and comfort that these meals provided to our clients…[they] made a huge impact by making food more accessible to our clients,” she says. “Many were struggling to secure food from other resources due to lack of availability, lack of income, waitlists, long lines, and lack of transportation.”

Hicks continues: “The grocery gift cards were extremely helpful to clients with low/no income, no home, or dietary restrictions. The gift cards allowed them to obtain the exact food items they needed to sustain themselves during the pandemic. These invaluable resources made food available to many who would have gone without.”

The addition of the Pride Pantry builds on pre-COVID-19 culinary innovations at the center designed to feed the community well.

The Los Angeles LGBT Center is also home to an innovative, intergenerational culinary arts training program for LGBT youth experiencing homelessness and low-income LGBTQ seniors. The center’s commercial kitchen, housed on the Anita May Rosenstein Campus, teaches participants basic culinary skills and offers professional development for jobs beyond the center’s kitchen. Before the pandemic, trainees finished the program—the brainchild of celebrity chef Susan Feniger who co-chairs the center’s board of directors—by completing an internship at local restaurants, catering companies, and other food service businesses.

“When we launched our culinary arts program, no one could have predicted that, one year later, we would be facing all of the challenges brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic,” center CEO Lorri L. Jean has said. “The demand for the center’s services has increased as a result of the pandemic, including a heartbreaking rise in food insecurity in our community. Our culinary arts program has been instrumental in helping us to rise to meet this need, both by providing meals for our seniors and youth, and by helping establish our Pride Pantry food bank that now distributes food from our locations throughout Los Angeles.”

Since the onset of the global health crisis, culinary students have prepared as many as 450 meals per day to feed the center’s senior clients experiencing food insecurity, the 100+ homeless youth who visit the Youth Center, and senior and youth residents at multiple center locations.

Like others of his generation, Ja-Jah has lived through another pandemic that devastated his community. “I saw the shock and the fear at the beginning of the AIDS pandemic, and then people came together,” he explains. “The Pride Pantry means that our community is still there. To ask someone: Do you have enough food? Do you need food? is the most meaningful question that you can ask,” says the senior, who notes that volunteers were warm and welcoming and put people at ease about receiving food assistance. “It is the most caring thing that you can do in a time of need—to be concerned about whether a person is eating or not.”

Next Steps

- Expand food insecurity screening to include all clients and evaluate data.

- Secure funding to ensure the Pride Pantry’s sustainability.

- Continue to respond to community need.

- Provide home delivery for clients beyond current, limited seniors service.