Teaming up for a pilot study

Neighborhood first looked at the digital forms options in its EHR, but it was insufficient. Innovation team members brainstormed with tech hub and looked at vendor solutions, but none were exactly what they needed. After exploring all the options, Neighborhood opted to build a solution in-house using iPads.

“We decided to start with consent forms – yes, no or multiple choice. We’re not doing medical histories yet,” says Carrillo. “We figured we’d start with some easy wins.”

A small team of five people decided to start by digitizing consent forms. After the concept was approved, the team developed an electronic questionnaire and chose a pilot site. “We told the front desk staff of the pilot site, ‘You are instrumental in making this a better product. We sought out their feedback and suggestions on how to improve the product and workflow.” And it wasn’t long before those suggestions started to pour in.

Assumptions vs. reality

From the feedback, the team quickly realized some of its assumptions didn’t pan out. Here are some of the major assumptions that required a pivot:

Assumption #1: The staff would be excited at the prospect of using tablets to save time.

The reality: Change is hard.

It was a challenge to convince office staff to change the way they had been doing things. Even after they started using the tablets, they had to be constantly reminded for the first few weeks to continue using them or they’d slip back into paper. To ensure tablets were used, the pilot site temporarily removed paper forms in the front office.

Assumption #2: All the tablets should be locked down or they would be lost, damaged or stolen.

The reality: Untethered tablets were safe.

The team assumed that patients would be able to complete the form in either the waiting room or an exam room, where they initially tethered the tablets. But patients were often being pulled from one location to another before the questionnaires were complete. “After feedback from the office staff on locking down the tablets, we realized, ‘Oh jeez, that was a terrible idea,” says Carrillo. “We decided to treat the tablets like piece of paper. Now we let people walk around with the tablets freely, and none have been lost, damaged or stolen.”

Assumption #3: Tablet formatting would be easy to get right.

Reality: It wasn’t.

The team intentionally tested the user interface at a clinic with a large geriatric population to be sure everyone could read the forms. After trying it out, the office staff was bombarded with complaints: The type was too small. The color scheme made it hard to read. And the margins were so small the buttons bled off the edge of the page, making it impossible to go to the next section. The team went on to new iterations with larger type, better color contrast, and larger margins so the buttons weren’t pushed into the bezel. Even so, the tablet had to go through more iterations before patients were satisfied.

Assumption #4: Tablets would be easier to use than writing on paper.

Reality: IT issues bogged down efficiency and quickly led to apathy.

The tablets worked well in some rooms and not other due to WiFi connectivity issues. That meant some patients got error messages when they tried to move from page to page or submit the form, which was frustrating. “The IT issues bogged down efficiency and quickly led to apathy,” Carrillo says.

Getting to Yes

Tablets are ubiquitous in health care – a 2017 survey found 80 percent of healthcare facilities are using them – but like Neighborhood, clinics and hospitals have had some unexpected challenges implementing them (See our 8 tips for successfully implementing tablets in health care).

The team leading the pilot rollout at Neighborhood were well aware of this and sought feedback from everyone involved: leadership, providers, medical assistants, front office staff, and patients.

After Neighborhood’s CMO and COO signed off on the proof of concept, medical assistants originally planned to have patients complete the questionnaires while they waited in the exam room. However, the medical assistants (MA) quickly realized this was impractical because the medical forms had information the MAs needed before they saw the patients. Instead, the front office was tasked with offering the questionnaire.

“It was surprising how vital the front office staff was in ensuring the project was successful,” says Carrillo. “Front office staffers were essential.” The pilot site’s office staffers, he noted, were essentially co-researchers empowered to give feedback and suggestions on how to improve the product and workflow. Without their constant feedback, he said, “errors, issues and pain points would likely have gone unnoticed and have led to patient frustration.”

After getting the front desk feedback, the team made some key changes to its game plan:

- Unlocking the tablets. “Tablets were initially tethered for security reasons. but we quickly removed the tethers since patients were rarely able to complete the questionnaires in one sitting,” said Carrillo. Patients were now free to carry a tablet from room to room, sometimes giving it back only when they were ready to leave. “I instructed the staff to treat them like a piece of paper, and none of the tablets have been damaged or stolen,” Carrillo says.

- Creating a new user interface. “We went through many, many, many, many changes before we got the “right” user interface,” says Carrillo, but it was worth it. Among other things, the team settled on larger type, a color scheme and wider margins that took care of most user complaints. (But, Carrillo cautions, “We still plan on making changes.”)

- Outfitting the clinic with new and better WiFi routers. Talking about WiFi problems in certain rooms, Carrillo says that the team anticipated something like that, but realized that patients getting error messages due to poor Internet connectivity “builds distrust in technology. If you give people bad technology, in the future they’ll say, oh, just give me paper form instead.” The new and improved routers took care of the pilot site’s connectivity problems.

The tablets were now available in English, Spanish, and Arabic (El Cajon, which Neighborhood served, has the second largest Arabic-speaking population in the United States and includes many Iraqi refugees. With the initial problems fixed, staff and patient satisfaction was higher. “The digital forms are great,” staff representative Gabriel Garcia said. “We should make all forms digital.”

With the pilot study concluded, it was time to roll out the tablets to the larger organization.

Metrics: When “misses” are instructive

That’s where things got bogged down for a while, according to Carrillo. “The original idea we had, we tested it and it got better,” he says. “We did not do as good a job rolling it out to the rest of the organization.”

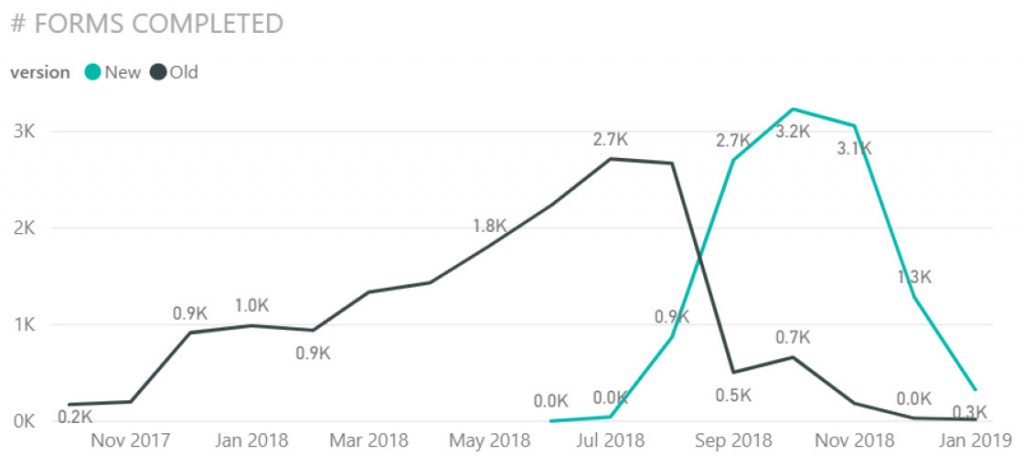

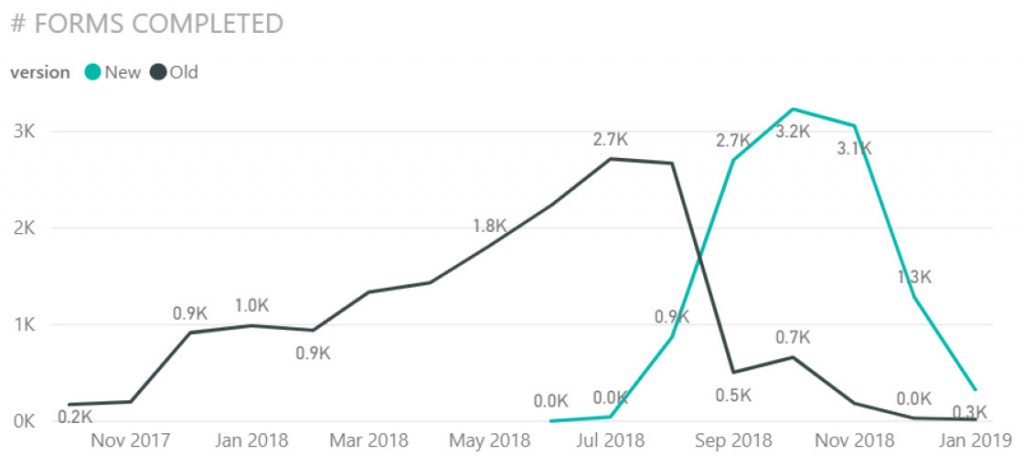

It wasn’t evident right away, but the new sites were having problems with the rollout. The innovation team had been giving regular monthly updates on the project at various meetings before “Digital Forms” officially became a standing agenda item in its Care Innovation Meeting. They weren’t getting negative feedback from the sites, so the problems went undiscovered for a while. Data analysis, however, showed that after an initial upsurge, the use of tablets org-wide had taken a nosedive (see chart).

“It was a failure of sorts,” says Carrillo. “We started getting some numbers back and tablet use was way lower than we expected. It turned out the rest of the sites had the exact same issues the pilot site had had – they were getting error messages, they were having internet connectivity problems, and they had had to put in IT tickets to get things improved.”

This was when talks with office staffers revealed what was going on. “At first the innovation group was saying, ‘Hey, why don’t they just report this and get it fixed,” says Carrillo. “But frankly, the front desk staff doesn’t have time to deal with IT tickets and everything else.”

“You have a workstaff that is under a lot of pressure to get people processed,” adds Carrillo. “Once something didn’t work, more staff went back to using paper. It felt like [the tablet system] was broken, so they didn’t worry about making the effort to use it. The more and more the errors happened, the fewer and fewer people were using the iPads, and pretty soon they were not being used at all at some sites. We were giving them a product, but it didn’t work correctly.”

Ownership of the problem was needed, and Carrillo was officially tasked with increasing the percentage of tablet use. “To make sure everybody was using this more, I told them if anything goes wrong, send me a message and we will get it fixed,” he said. “And essentially, the floodgates opened. I received emails and sent them to our programmer or IT department to correct the issue, I also cc’d the group using the tablets so people saw we were actually doing something. Staff has to see their suggestions don’t fall into a black hole. Within 48 hours they would see a change has been made and see their input had made a difference.”

It worked. Since assigning someone as project owner over the last two months, Carrillo says, “we’ve gotten 100% more usage at some sites and over 64% increase in organization-wide usage” (See chart, above). Despite occasional challenges, he is gratified with the results. “Before this, patients would answer the forms and then someone would have to type it in – it adds the possibility of error. This has saved us a lot of time and a lot of money.”

Lessons Learned

Front-line staff must be actively engaged. “Without them giving us feedback, we would never have known what needed to be improved,” says Carrillo. “Also, when feedback is given, make sure some action is taken on it. The more staffers saw their suggestions being implemented, the more suggestions they gave us!”

Be prepared to be wrong. “Workflows we meticulously worked on during multiple meetings turned out to be impractical when implemented,” says Carrillo. “We had to adapt and adapt quickly.”

New tech/solutions break. Assign a project lead to own the project; and make sure everyone knows that lead is the go-to person to resolve issues. “Make sure you have a good contact in IT and that IT issues are reported and dealt with promptly. Otherwise, staff/patients will become disillusioned, you will lose buy-in and your solution will fail. The lesson? In every phase of a project, you need feedback.”