The Paper Chase: “A Pretty Crazy Process”

The original peer review process had become a headache for administrators; worse, it had drifted out of compliance with the Shasta clinic’s bylaws and policies. “It was a paper process at the time, and the inefficiency was tied up in the paper chase,” said Charles Kitzman, chief information officer of Shasta Community Health Center. “It was very labor intensive — we were lucky to be reviewing 600 charts out of 140,000 patient visits annually.” He ticked off the reasons: a wasteful manual data entry process, “lukewarm participation” from the staff, and feedback for doctors that was often less than helpful.

The original peer review process had become a headache for administrators; worse, it had drifted out of compliance with the Shasta clinic’s bylaws and policies. “It was a paper process at the time, and the inefficiency was tied up in the paper chase,” said Charles Kitzman, chief information officer of Shasta Community Health Center. “It was very labor intensive — we were lucky to be reviewing 600 charts out of 140,000 patient visits annually.” He ticked off the reasons: a wasteful manual data entry process, “lukewarm participation” from the staff, and feedback for doctors that was often less than helpful.

“The old process was pretty crazy,” Kitzman recalled. “We’d have to pull the charts, take a sharpie and de-identify everything, then send them out to five locations, including a van that’s a medical office on wheels. You’d have folks who are super-diligent and get the reviews back right away, and others who would sit on them and hold up the process. It was very frustrating.”

Another frustration was that some doctors would rate a physician’s treatment of a patient as “good” or “poor” without providing any details. Since the review process was intended to help primary care doctors learn from specialists and their peers, the lack of feedback undermined the process.

“We didn’t want a doctor’s performance to be marked down without an explanation,” said Kitzman. “That wasn’t the kind of feedback that could help anyone improve. Instead, it could be seen as punitive.” Not surprisingly, some doctors complained about their reviews. It was time for a change.

Reviewing the Review System

Rather than just reviewing a doctor’s notes on a patient’s visit, the Shasta clinic’s five-person peer review committee felt that they could better analyze care coordination if they had access to a patient’s entire chart. The members hammered out some goals:

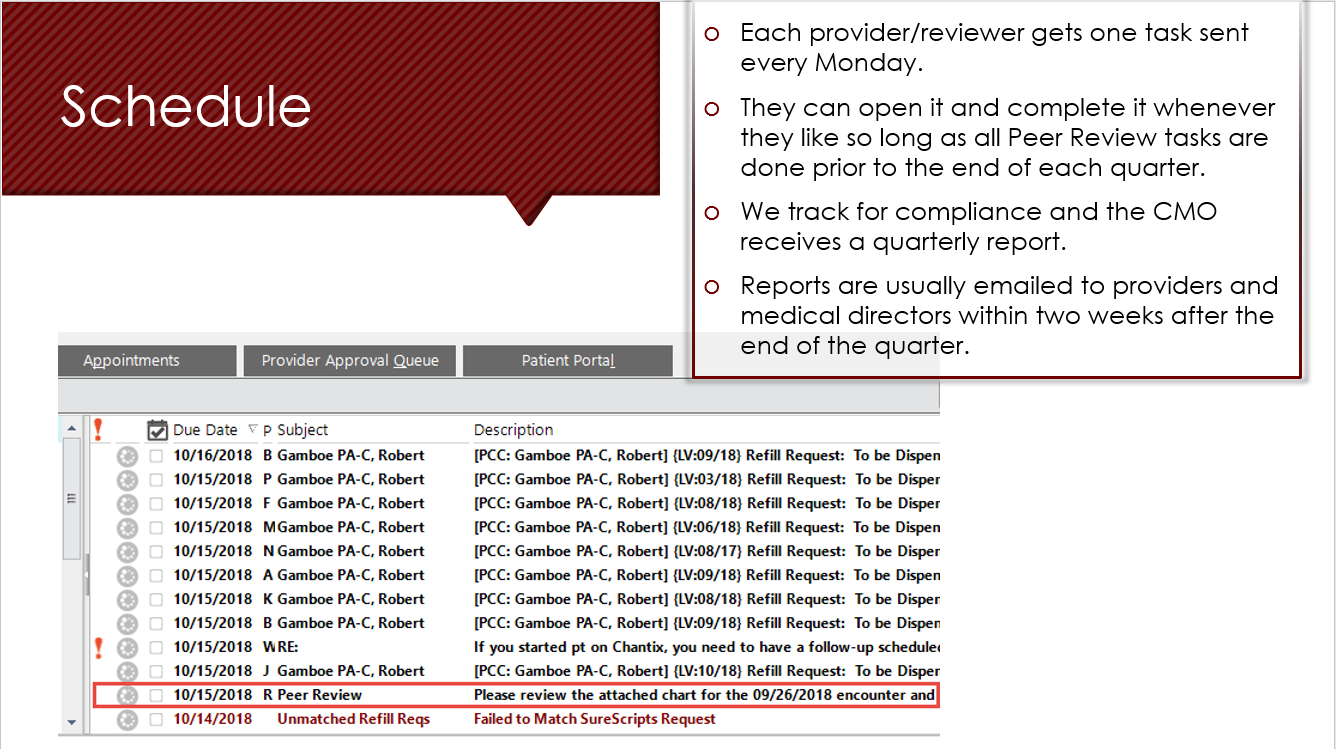

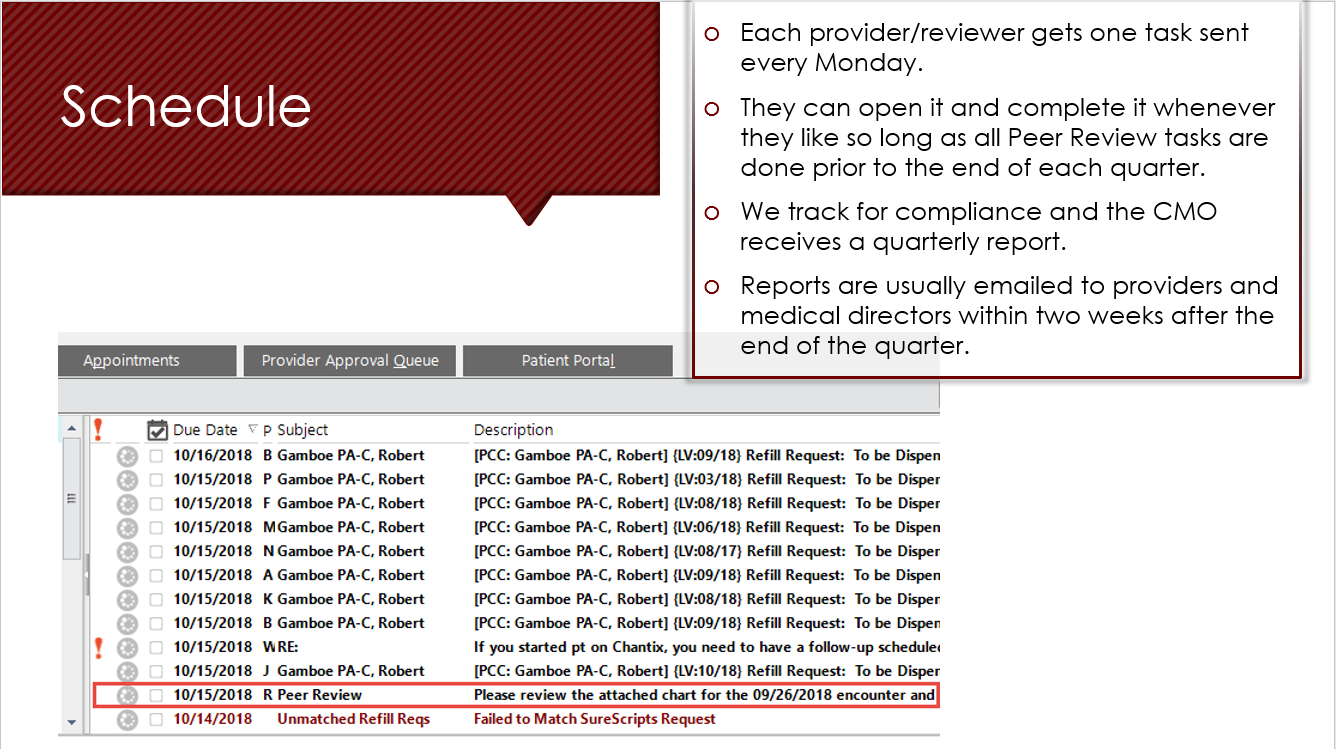

- A sustainable schedule for peer reviews. In some years, the center had only been able to collect two cohorts of data, and its policy required four.

- Questions for peer review that were relevant and required feedback if physicians were “marked down.” If the performance was deemed below the standard of care, Kitzman explained, it was crucial to find out why.

- Elimination of the time-consuming manual data entry process and the “tedium” involved in gathering results. In particular, the committee wanted to stop having to hound providers with constant reminders and visits.

A digital process would help meet all these goals with relative ease, the committee decided. The next step was a pilot project to see how it worked.

Looking for What Worked

The committee didn’t want to waste time rebuilding the peer review survey, so it began making the existing forms digital. The five providers on the committee also decided to test out the process on themselves, serving as a beta group that performed online reviews and provided feedback for three months, or one cycle, before expanding it to the wider group.

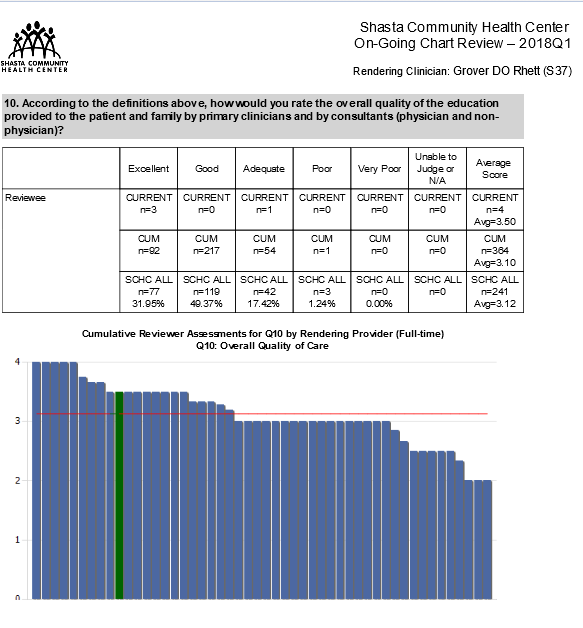

In addition to refining some technological details and honing the questions, the committee had to figure out analytics. This meant moving from a licensed product (STATA) to a new system that would analyze the results, make the outcomes anonymous and compare the reviewees to their peers and clinical averages, all on the clinic’s own system using SSRS (SQL Server Reporting Services).

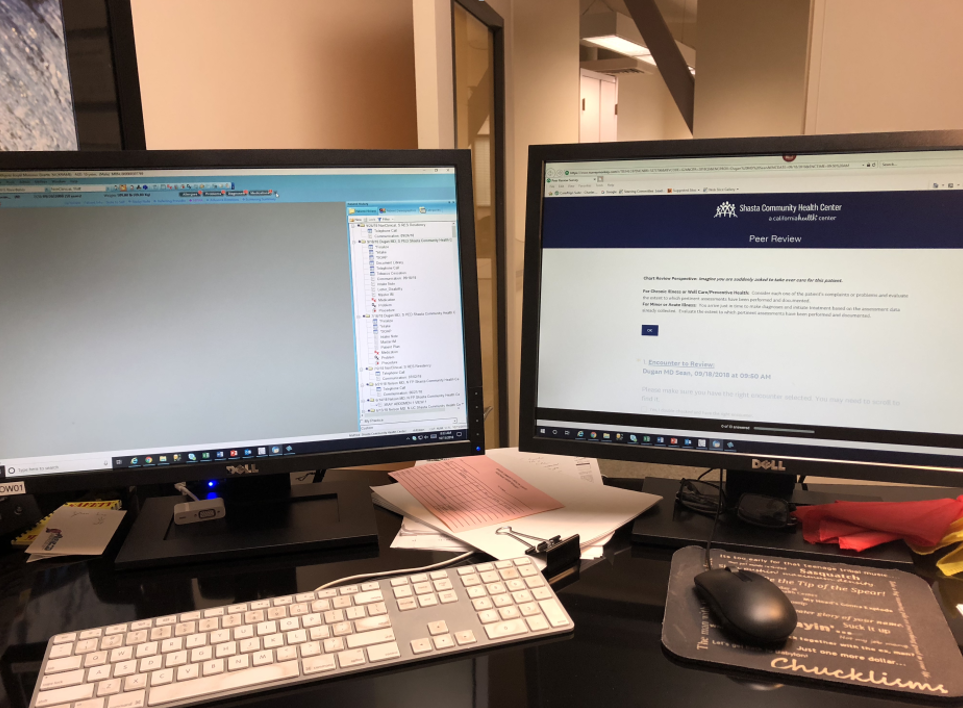

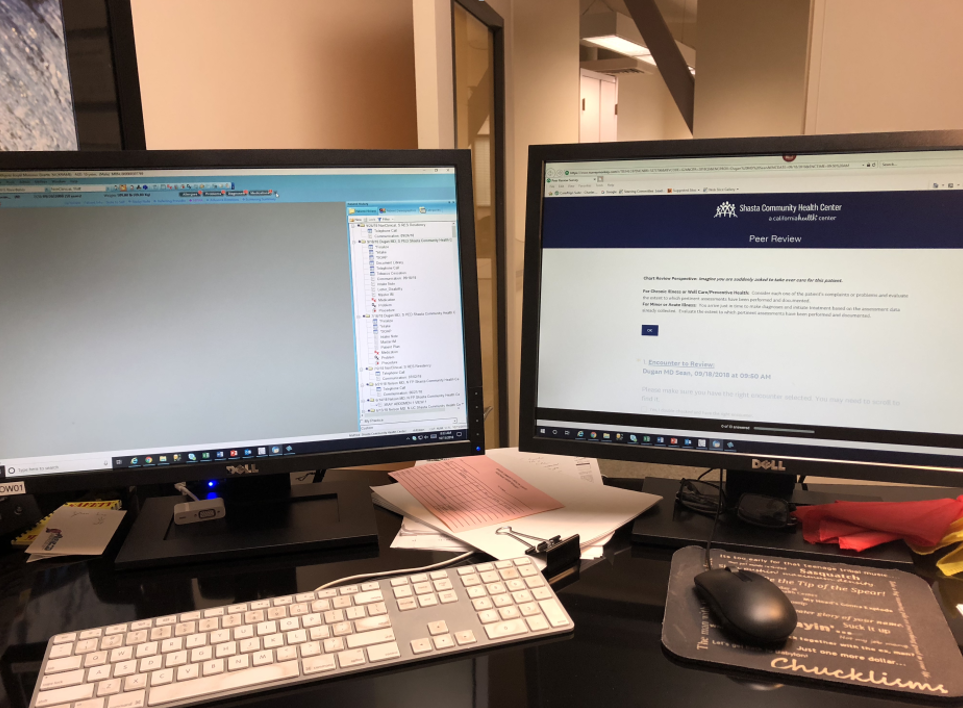

After that was completed, the rollout began. One early hurdle was that many providers had trouble using a split screen on the computer to read the chart and answer the survey. Getting two monitors to each provider let them keep the Survey Monkey peer review on one screen and the electronic medical record (EMR) on the other — a much easier solution. (Shasta chose Survey Monkey, Kitzman says, because the health center already had an account and found it easy to use; plus, it supported the API so that no protected health information, or PHI, was posted.)

With the added ease of review, the committee decided to assign a chart a week to each provider, thus doubling the number of charts providers reviewed.

A Question of Privacy

The thorniest issue was whether to have the peer reviews be unblinded. “We had many lengthy conservations about the potential impact of implied bias in an open and transparent process,” Kitzman said. “Often reviewing providers would know the patient whose chart was being reviewed, and they may have even cared for the patient at some point. Certainly, they would know who was delivering the care. Ultimately the group decided that the benefits of transparency would outweigh any issues with bias.”

The committee did put in some safeguards, however, for cases in which bias would be almost impossible to prevent — i.e. family members or husbands and wives reviewing each other’s charts. The solution? An exclusion list to prevent family members from reviewing each other.

Buying In

In the medical field, technological solutions embraced by administrators may often rub staff members the wrong way — especially in the bumpy early phase of a roll-out. This wasn’t true of Shasta Community Health Center, however. Once providers each had two monitors for convenience, which made the system easy to use, they were more than happy to leave the old process behind. (The doctors in the mobile van, like the other physicians at the clinic, were encouraged to do chart reviews in the privacy of their offices — all of which were equipped with dual monitors.)

“So glad to be rid of paper in this process,” said Dr. Doug McMullin, medical director of the Center’s residency department. Describing the online reviews as “accessible” and something that easily fit into the providers’ workflow, he concluded the digital reviews were a “great addition” to the clinic.

Echoing these sentiments was Dr. Kelly Duane Carter, a pediatrician and peer review committee member at Shasta. “I think the digital chart review is an excellent system,” he said. “Once I learned the system, I could quickly scan the chart looking for the pertinent information and then fill out the questionnaire. It has tremendously increased my efficiency, and I think it has helped us to obtain good information in the most efficient and pain-free way possible. I’m very thankful for it.”

Kitzman agreed that after dealing with technical problems, buy-in to the tech solution was strong across all sectors. “The providers liked the process from the start,” he said. After some moderate changes to the survey and some additional controls, the process has remained largely unchanged – including some providers’ tendency to procrastinate. “Most of the providers — about 85 percent — now do their peer review charts every week,” he says. “But a few still hoard them up and then sit down at the end of the quarter and knock them all out.”

Results

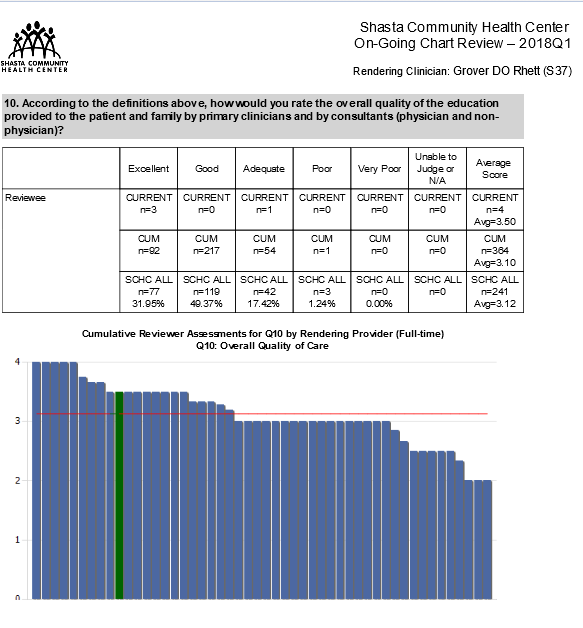

Now that the clinical peer reviews are digital, Shasta is able to do them quarterly (“with a real drop-dead date for filing them,” adds Kitzman). The online review system has allowed them to double and perhaps triple their number of provider reports and to be compliant with their own policies and with outside oversight agencies. “We’re on pace for 2,000 charts to be reviewed every year now,” said Kitzman. “We try to do different patients each time, too — not just frequent flyers.”

Lessons Learned

- The threat of bias has not turned out to be much of a factor in online peer reviews. “Many providers freely admit that after working here for a period of time, efforts to anonymize the data are ineffective anyway,” Kitzman reported. “They learn quickly the styles of each clinician and can confidently guess who they are reviewing.”

- Rubrics help. Even after the switch to online peer reviews, evaluations were still marked by tremendous variability. In response, the peer review committee is redefining the criteria for “excellent” care, “very good” care, and so on — a change intended to make the reviews more consistent.

- Benefits tend to ripple across the organization. The chart reviews serve a dual purpose of reviewing scribes’ work as well.

Next Steps

The peer review committee will continue to redefine the rubrics to provide better guidance on questions that tend to yield inconsistent answers. “We also want to send out some messaging about negative reviews, to the effect of ‘put yourself in the other doctor’s place,’” said Kitzman. “We are trying to improve care and training, not to write reviews that are punitive or unfair.”

In that vein, the committee will also try to focus some additional review questions on specific disease management strategies for diabetes, COPD, and other illnesses that align with the center’s quality objectives. It also hopes to develop a behavioral health chart review and to automate the review distribution process. Finally, they hope to automate a way to send reminders to reviewers falling behind to pick up the pace before their performance review.

The original peer review process had become a headache for administrators; worse, it had drifted out of compliance with the Shasta clinic’s bylaws and policies. “It was a paper process at the time, and the inefficiency was tied up in the paper chase,” said Charles Kitzman, chief information officer of Shasta Community Health Center. “It was very labor intensive — we were lucky to be reviewing 600 charts out of 140,000 patient visits annually.” He ticked off the reasons: a wasteful manual data entry process, “lukewarm participation” from the staff, and feedback for doctors that was often less than helpful.

The original peer review process had become a headache for administrators; worse, it had drifted out of compliance with the Shasta clinic’s bylaws and policies. “It was a paper process at the time, and the inefficiency was tied up in the paper chase,” said Charles Kitzman, chief information officer of Shasta Community Health Center. “It was very labor intensive — we were lucky to be reviewing 600 charts out of 140,000 patient visits annually.” He ticked off the reasons: a wasteful manual data entry process, “lukewarm participation” from the staff, and feedback for doctors that was often less than helpful.