Catalysts for Change

In our 2018 cycle of Catalyst, EOYDC staff learned about human-centered design, and used those strategies to improve their approach to mentoring Youth Leaders, and helping them learn trauma-informed care (TIC) practices.

EOYDC emphasizes TIC at every level of the organization. The young people who come to EOYDC are from neighborhoods where poverty, racism, and violence are facts of life, and many experience chronic stress and trauma as a result. Research shows that trauma-informed care practices can ease stress and help prevent retraumatization.

According to Selena Wilson, EOYDC’s Vice President of Organizational Effectiveness, “As an organization, it is critical that we learn to recognize signs of trauma and respond in a healing way, versus a way that is retriggering. We try to create a healthy environment without stress and trauma, but we recognize that when our kids leave us and go back to their neighborhoods, they are likely to be retraumatized, so we also help them learn healthy coping skills to handle difficult situations no matter when they encounter them.”

In line with their commitment to TIC, EOYDC staff use “positive discipline” instead of punishment if a child acts out. “Positive discipline challenges the idea that to make a child do better, you have to make them feel worse,” Wilson explains. “The goal is not to make them feel bad about themselves, but to help them understand how to behave differently.”

Positive Discipline techniques include taking a child aside and talking to them (without blame or anger) about their behavior, finding out what is behind it, examining feelings and brainstorming more positive ways to deal with difficult emotions and situations. The techniques take time and practice, and often don’t show immediate results.

EOYDC administrators found that, although its staff was effectively using TIC practices, some of its Youth Leaders (teens 15 and up who support and mentor younger students) were having trouble implementing them, despite training. They realized that for many of the Youth Leaders, this approach was counterintuitive. Says Wilson. “They were used to traditional discipline: ‘What you did is wrong. Go to the principal’s office.’ They were used to being talked to, not to going deeper and looking at the roots of the behavior.”

Understanding the Problem

Before participating in Catalyst, the EOYDC team assumed that Youth Leaders were not grasping TIC techniques because the training they received was not sufficient or somehow not appropriate for the age group and their particular needs. They initially planned to revamp training materials with the Youth Leader audience in mind.

But the Catalyst process, including journey mapping and show and tell interviewing, helped the team redefine the challenge they faced. In fact, they learned that after training, Youth Leaders had a good understanding of TIC, but had trouble putting it into practice. “What we thought was the problem— insufficient training — was not actually the problem,” says Selena Wilson. “The kids told us: ‘No, the training is good. It is when I am trying to do it the moment that I have problems.”

The team realized there were two facets of the problem:

- In the heat of the moment (for example, when a younger child acted out) Youth Leaders had trouble implementing the TIC techniques they’d learned; and

- Because many Youth Leaders have experienced trauma themselves, it was difficult for them to summon the patience and empathy that TIC practices require.

Identifying Solutions

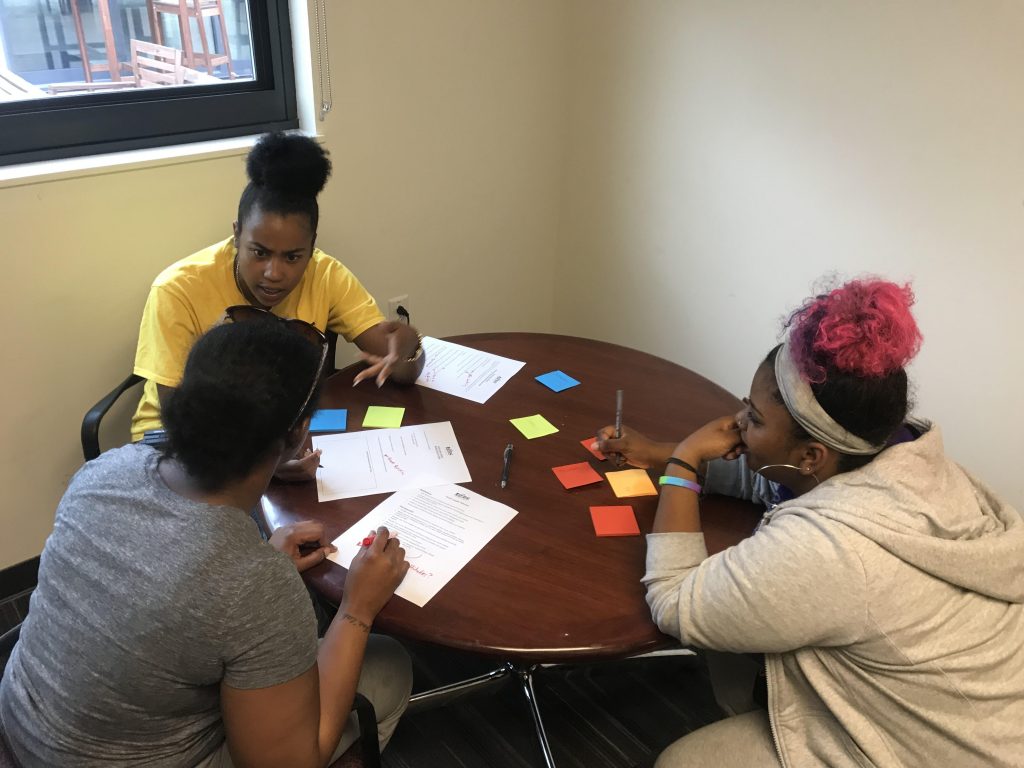

“See and Experience” phase of the Catalyst process helped the team realize that they needed to provide Youth Leaders more comprehensive support, including coaching on how to implement TIC practices in real-life situations, and ongoing emotional support and tools to help them when they experienced their own stress.

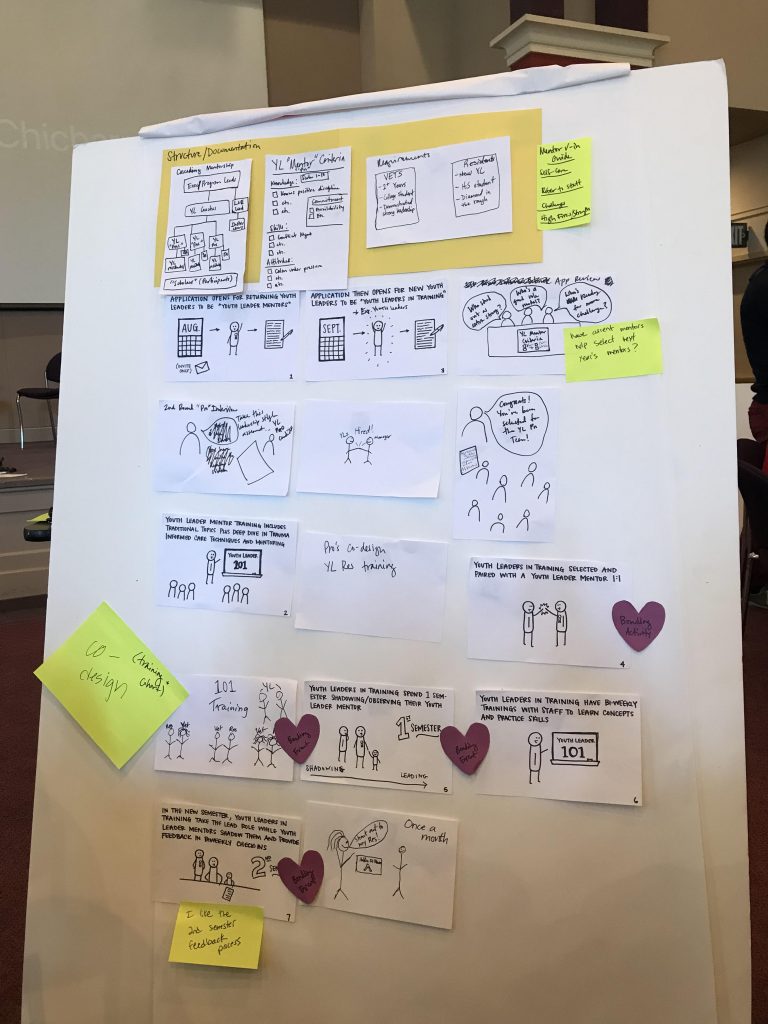

The “Imagine and Model” phase of the Catalyst process helped the team weigh and evaluate different solutions to the problem.

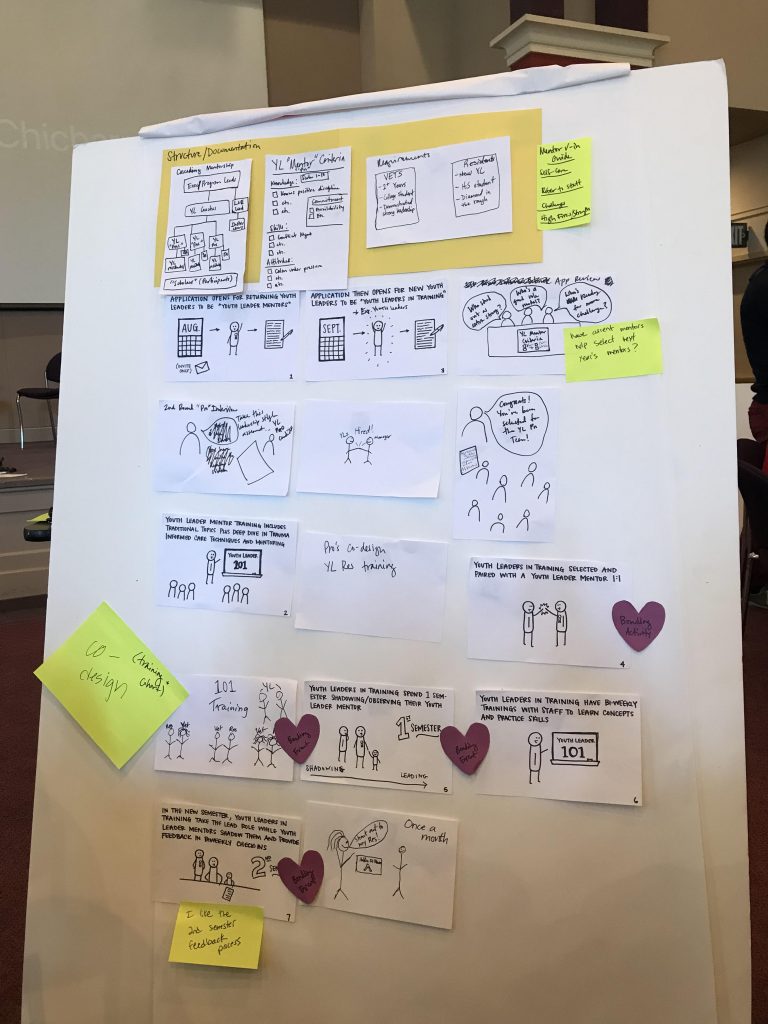

They ultimately decided to develop a new position that would provide near-peer support for Youth Leaders. They modeled the new position on the “residency” stage of medical training: medical residents work under the supervision of an experienced clinician. As Selena Williams explains, “A young surgeon may know how to do surgery but in the moment may be too nervous to use the skills effectively. As a resident, they shadow a more experienced surgeon for awhile to learn how to use their skills in difficult, high-stress situations.” Similarly, in the new plan, new Youth Leaders at EOYDC would receive coaching and support from a more experienced and slightly older peer.

From Theory to Action

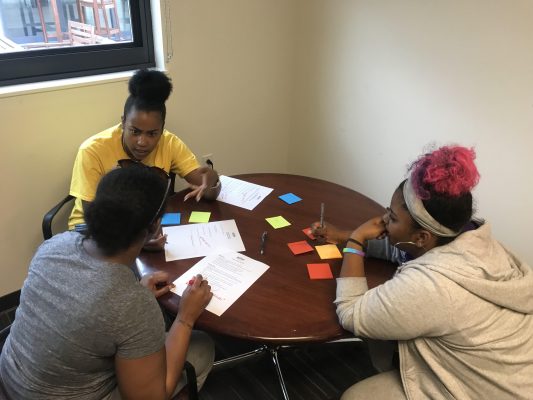

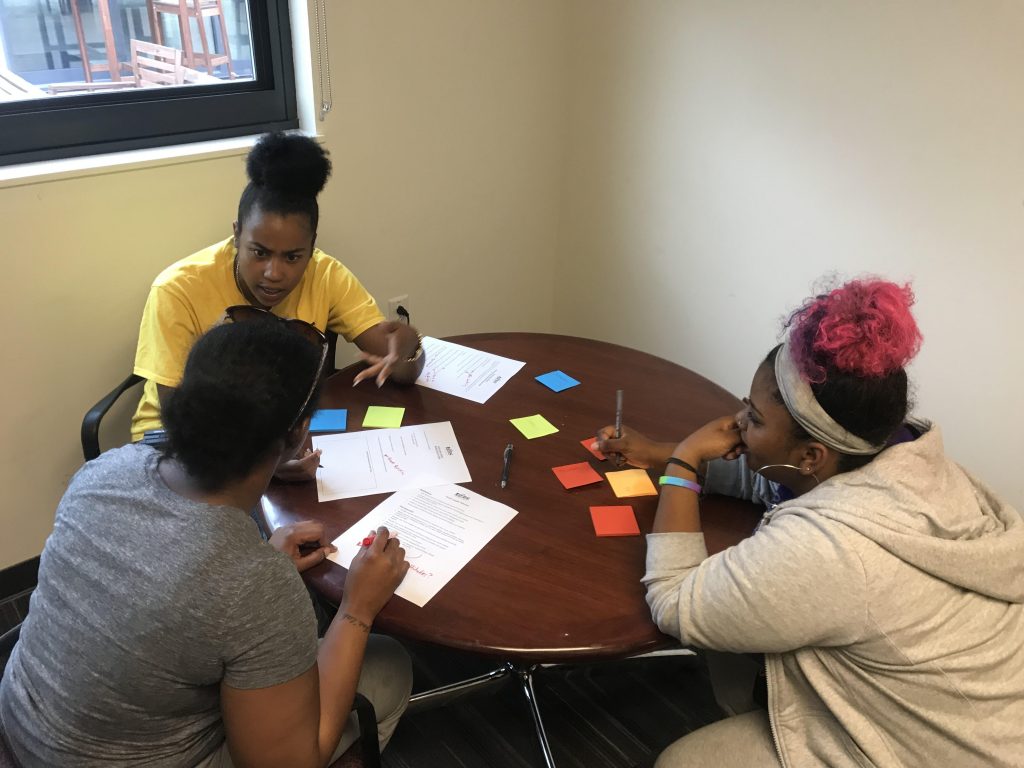

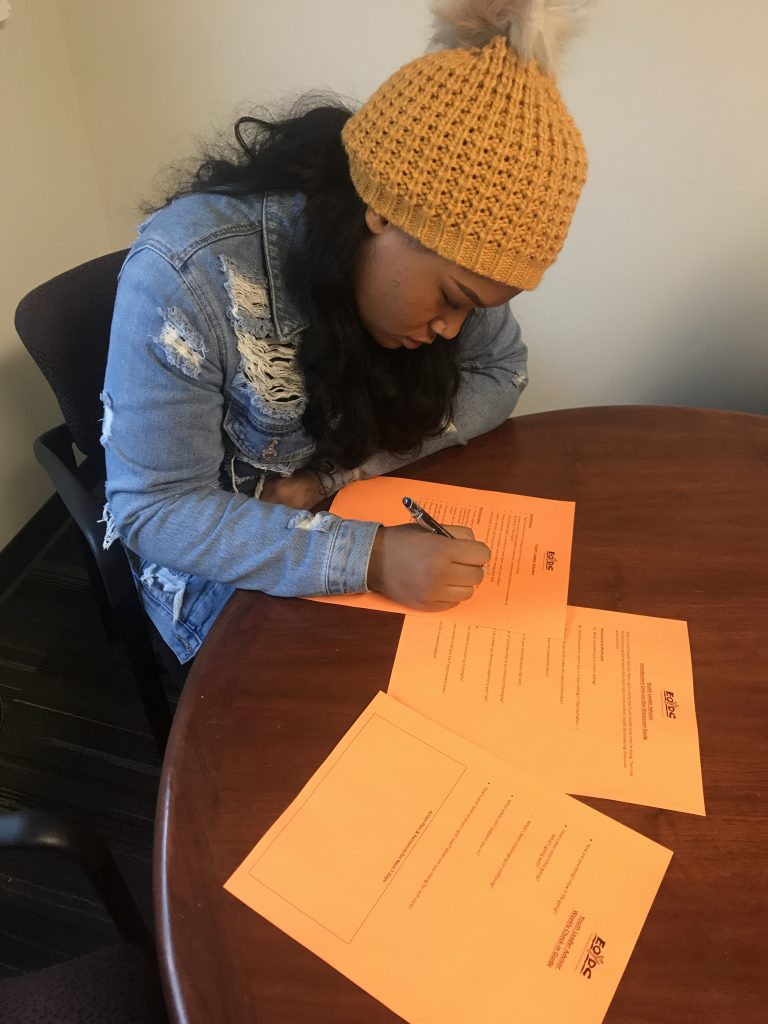

It was now time to “Test and Shape” the new plan with those directly affected: the youth members of the EOYDC community. The team worked with youth to co-design and name the new position, and decided to call it “Youth Leader Advisor.” With input from youth participants, they also developed a one-on-one check-in guide, which Youth Leader Advisors would use in regular check-in meetings with the Youth Leaders under their supervision.

Under the new structure, Youth Leaders were assigned a Youth Leader Advisor, who they would initially shadow. Daily check-ins would allow Youth Leaders to reflect on the day and ask questions and receive advice and support. Unlike Youth Leader Coaches, the Youth Leader Advisor would not be evaluating their mentee’s performance, giving Youth Leaders the freedom to ask questions and express frustrations they might be uncomfortable sharing with a coach who was evaluating their performance.

During the six-week summer program, the new position was tested with a small group of nine high and college students and feedback was gathered for the next iteration during the school year.

A couple of issues became evident early on:

- Some youth were confused about how the “Youth Advisor” position was different from the already established “Youth Leader Coach” role. Staff met with both Coaches and Advisors to make the differences clear, but some confusion persists, and will be addressed in the next iteration.

- Experienced Youth Leaders didn’t feel they needed a Youth Leader Advisor. First-time Youth Leaders, on the other hand, found the additional support extremely helpful, especially the chance to observe the Youth Leader Advisor as they implemented TIC practices.

Results

In the initial pilot, which included nine high school and college student participants, the new approach was successful: 100 percent of new Youth Leaders assigned to a Youth Leader Advisor found it to be helpful.

An added but unexpected benefit of the new position: becoming a Youth Leader Advisor had positive advantages for the Advisors themselves. The Advisors liked their new roles, and felt that the added responsibility helped them improve their interpersonal and leadership skills.

“The new role helped Advisors develop their own skills, because when you teach a skill something, it deepens your own skills,” says Wilson.