Over the last year, CCI allies helped us explore an important question: How can partnerships strengthen and enhance the reach of safety net institutions?

Quality health care is essential, of course, but there are many basic needs it doesn’t address. Without access to adequate food, housing, transportation, and psychological support, which play such a key role in individual and community health and wellness, patients will not be as healthy as those in affluent zip codes. However, these needs — the “social determinants of health” — fall outside the scope of many safety net health centers.

CCI is committed to creating a more human-centered and equitable system of health care. Like some other organizations, we wanted to explore whether forging partnerships between medical and other community-based organizations would result in a more comprehensive approach to health and community wellness. This work, launched in the summer of 2019 as a pilot program with the Blue Shield of California Foundation, was designed to explore the potential of partnerships to more effectively integrate services and address social determinants of health.

But we wanted to try something different. We learned from research and conversations with experts that most existing community partnerships to date have been implemented on a large scale, with as many as ten partners from diverse fields. We decided to explore a model of partnerships on a small scale to allow participants to try different approaches, switch gears when necessary, and adapt to changing circumstances quickly and nimbly, then scale solutions that worked.

With this small but mighty partnership model in mind, CCI reached out to two long term allies and alumni of our human-centered design training program — the Los Angeles County and USC Medical Center Primary Care Services (LAC+USC) and East Oakland Youth Development Center (EOYDC) — to develop and test our pilot. CCI helped the organizations conceive, develop, and refine their goals for the partnerships, using human-centered design tools and providing support and encouragement along the way.

The result? As we describe in more detail below, the pandemic and the subsequent lockdown forced both LAC+USC and EOYDC to revise their initial plans in order to adapt to unprecedented challenges and a rapidly changing environment. Both did so with agility and compassion. COVID-19 made both organizations’ work — including the goals they pursued for the partnership pilot — even more critical, in ways no one could have anticipated when the project was conceived. In the end, the pandemic served to underscore the potential and power of partnerships to help community-based organizations more effectively address the needs of the populations they serve.

Los Angeles County and USC Medical Center Primary Care Services (LAC+USC)

Food Insecurity In Los Angeles County

When CCI approached staff at Los Angeles County and USC Medical Center Primary Care Services (LAC+USC) about participating in our pilot, they decided to focus on food insecurity. “Food insecurity” is defined as a lack of access to a consistent, nutritious supply of food sufficient to live a healthy life. According to the organization, FeedAmerica, 11.5 percent of Americans experienced food insecurity in 2018.

Rates are higher than the national average in Los Angeles County. “Local public health data estimated food insecurity at around 20 to 30 percent,” according to Manual Campa, a family physician and Primary Care Service Clinic Director at LAC+USC, who says that screening at his own clinic identified many patients who didn’t have consistent access to food.

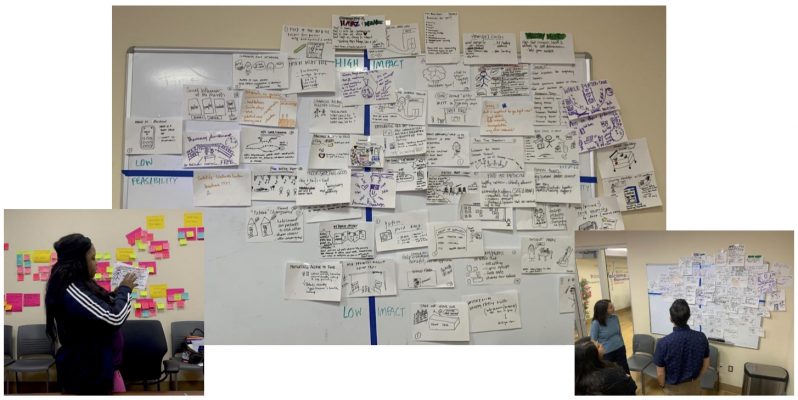

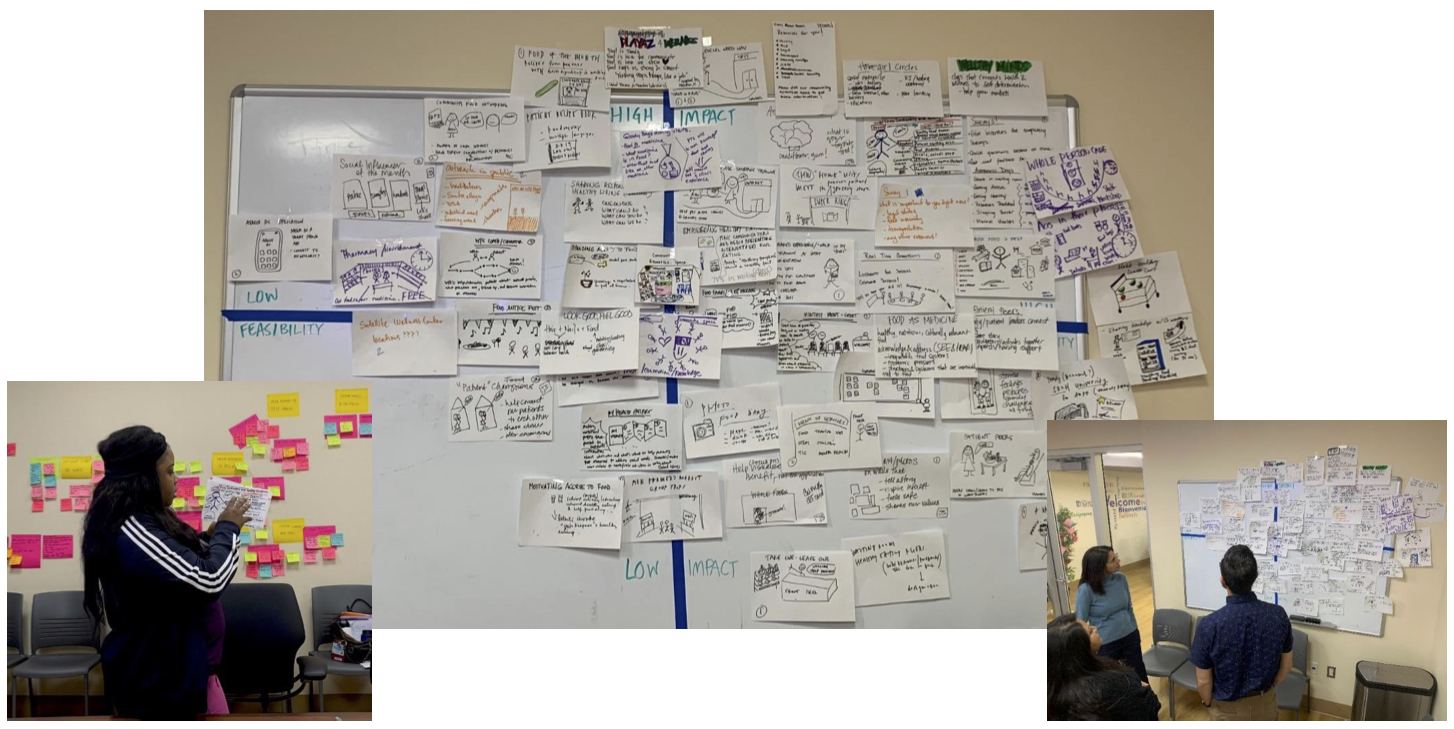

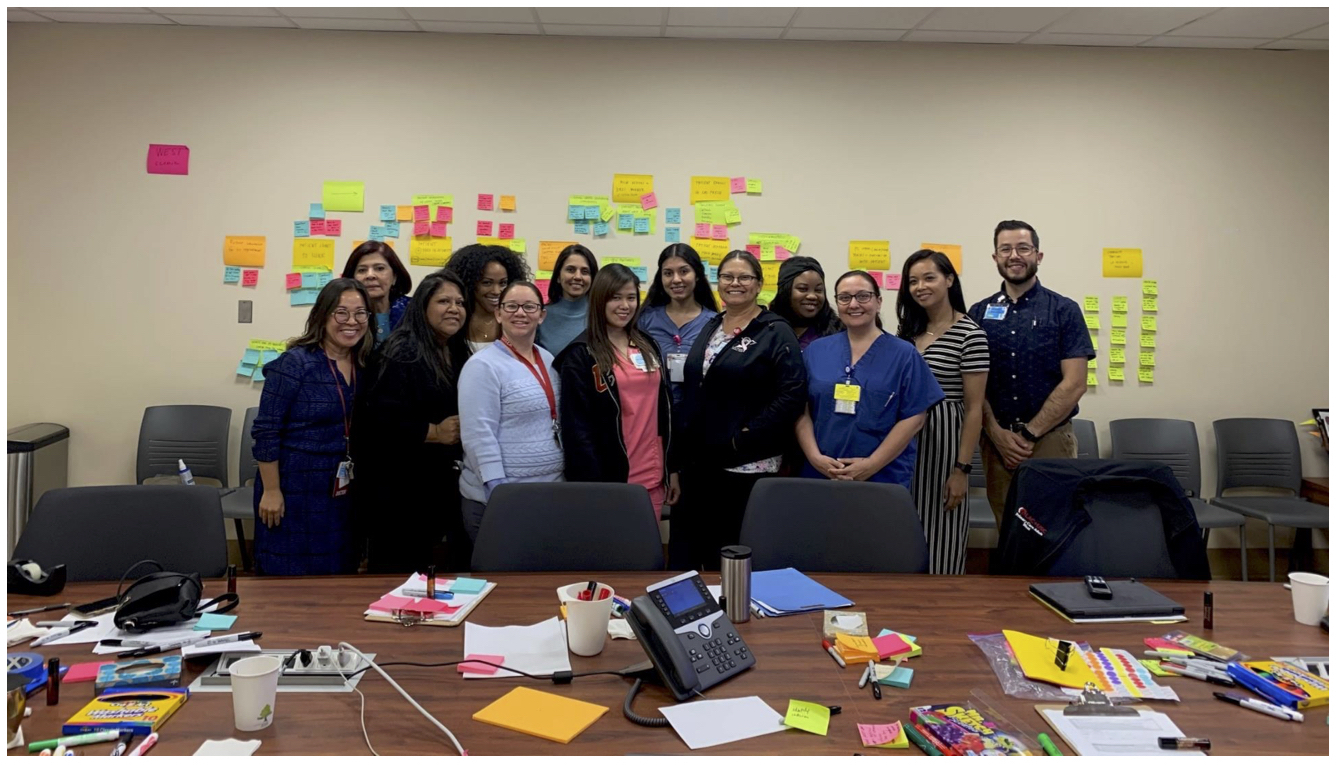

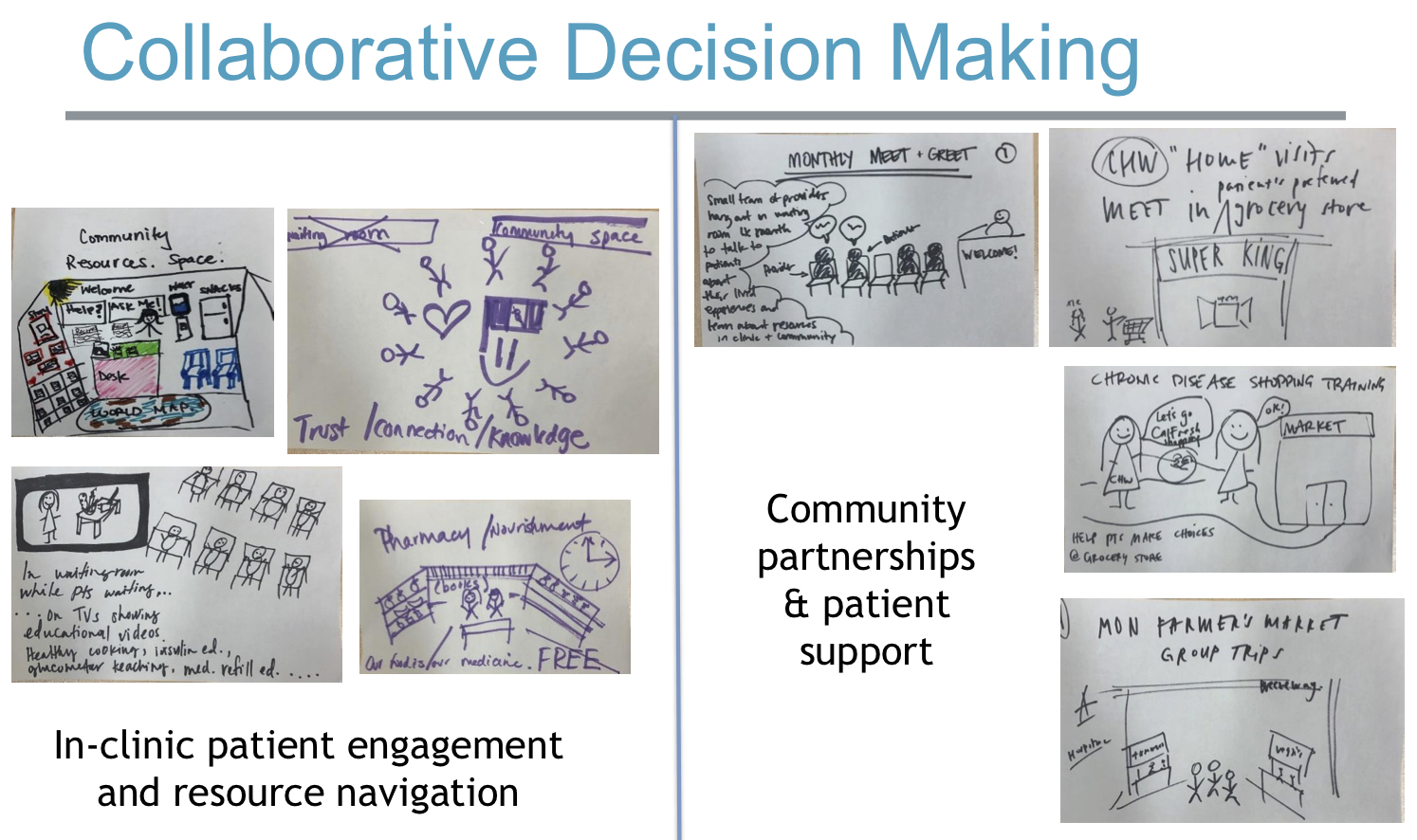

To help get the pilot off the ground, CCI met with staff at LAC+USC for a site visit in July 2019, and then conducted three days of design sessions at the end of October 2019. The staff at LAC+USC had already participated in CCI’s Catalyst training to learn human-centered design skills. The October sessions allowed them to put what they’d learned into practice as they used human-centered design tools including brainstorming, observation, and journey mapping to design the partnerships, incorporating the needs of patients and partners alike.

Manuel Campa, who has participated in Catalyst and worked as a Catalyst coach, says he used the training techniques constantly during the partnership project. “Tools like empathy-building and understanding end users really helped us create buy-in to do this work,” he said. “Throughout the process, I kept the human-centered design concepts in the back of my mind; I’ve continued to use them more recently when we created new drive-in services for pediatric vaccines and COVID-testing. Overall our teams have learned that they are not going to do something without first thinking about it from a human-centered perspective. That change has been palpable over the last few months.”

Partners in Food

Staff at LAC+USC’s primary care services clinic had already been exploring ways to tackle food insecurity before the pilot began. They had screened patients about nutrition needs, and developed relationships with the Los Angeles Regional Food Bank and the Wellness Center, a nonprofit organization located on the LAC+USC campus that offers a variety of services including housing support, nutrition classes, and mental and behavioral health services.

In November 2019, LAC+USC Primary Care Services and The LA Regional Food Bank teamed up to launch their first food distribution. The need was enormous: on the day of the initial distribution, lines stretched out the door and they ran out of food before the distribution was over. They worked with the Food Bank to add another distribution day (there are now two per month) so they could serve more patients.

Primary Care Services staff used the food distribution as a way to educate patients and connect them to other sources of support. On food distribution days, patients identified through food insecurity screenings met with community health workers who provided information on local food and nutrition resources and how to access them. These patients were first in line at the distribution site when it opened.

Through January and February 2020, the food distribution program hummed along and the number of people who came to pick up food continued to rise. “It was a cross-discipline, cross-organization partnership that was really successful,” Campa said.

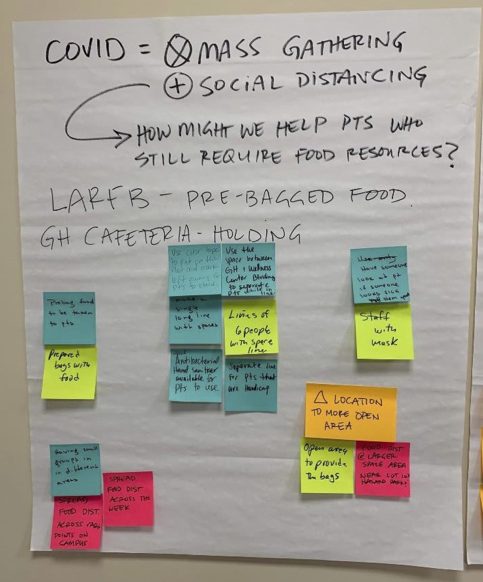

Pivoting After the Lockdown

Then COVID-19 hit. The Wellness Center closed down (as of this writing, it is open for televisits only). According to Dr. Campa, all the other partners — Primary Care Services, the LA Regional Food Bank, and LAC+USC administrators — were determined to continue the food distribution, because, as Campa explained, “We all agreed that with looming economic impacts from unemployment, food insecurity was something we still very much wanted to prioritize. So we worked with the Department of Health Services to figure out what safety precautions we needed to take, put those into place, and basically went on uninterrupted with our food distribution.”

Then COVID-19 hit. The Wellness Center closed down (as of this writing, it is open for televisits only). According to Dr. Campa, all the other partners — Primary Care Services, the LA Regional Food Bank, and LAC+USC administrators — were determined to continue the food distribution, because, as Campa explained, “We all agreed that with looming economic impacts from unemployment, food insecurity was something we still very much wanted to prioritize. So we worked with the Department of Health Services to figure out what safety precautions we needed to take, put those into place, and basically went on uninterrupted with our food distribution.”

Campa and his colleagues were right that the pandemic would only increase food insecurity as the lockdown forced many businesses to close and put growing numbers of people out of work. The distribution site went from serving about 300 to 400 people to over 1,000 people after the lockdown. Observing the need, Campa and his colleagues realized they could provide patients with more than a bag of food. They brainstormed ways to connect patients with government resources, including CalFresh (California’s food stamp program), which the state expanded after the pandemic hit. Clinic staff began passing out CalFresh informational flyers along with bags of food.

But after observing the results for a few weeks, clinic staff realized that passing out flyers wasn’t enough. They decided they had to do more to ensure patients received the government resources they needed. Clinic staff reached out to CalFresh enrollment specialists to see if they could connect them directly with patients during the food distributions.

“Now at each food distribution, we have a phone and if a person says they don’t have CalFresh, we ask them if they want to apply,” Campa explained. “If they say yes, we connect them to an enrollment specialist to walk them through their application. We also connect patients who have been denied CalFresh benefits with medical/legal services provided by the Department of Health Services to help them navigate the process. It’s been a really effective way to get our patients the benefits they need.”

Campa is pleased about how well the partnership project has unfolded and adapted to changing needs, adding new partners along the way. “Since the pandemic, we’ve strengthened our partnerships,” he says. “For example, the people at the Food Bank weren’t accustomed to using PPE (personal protective equipment). So we staffed the food distribution with nurses who know how to don PPE and are trained to identify illness, too. Then we figured out that our patients had legal needs as well, so we forged partnerships with the medical/legal team.”

The Food Connection

It’s been a learning experience for Campa and his staff as they’ve identified the connection between food insecurity and other social determinants of health. “Food insecurity intersects with immigration issues, with partner violence —many people lose their financial stability when they leave a violent partner — and, of course, homelessness,” Campa said. “Based on what we’re learning, we’re asking ourselves what we can do as a primary care team to help people on an individual and also on a population-based level.”

In the coming months, there are discussions on how to create a sustainable food pantry model on the LAC+USC campus, where patients can pick up food in between distributions. “Addressing food insecurity is now ingrained as a priority at LAC+USC,” he said. “Our work has been highlighted, and now some of our sister clinics in the system have adopted this model of having CalFresh support at their distribution sites. We’ve been a leader in this, which is something we are proud of.”

East Oakland Youth Development Center (EOYDC)

It Takes a Village

The East Oakland Youth Development Center (EOYDC) is another longtime CCI ally. When we asked organization staff to participate in our pilot, they were eager to explore how partnerships could strengthen their work and improve their ties with their community.

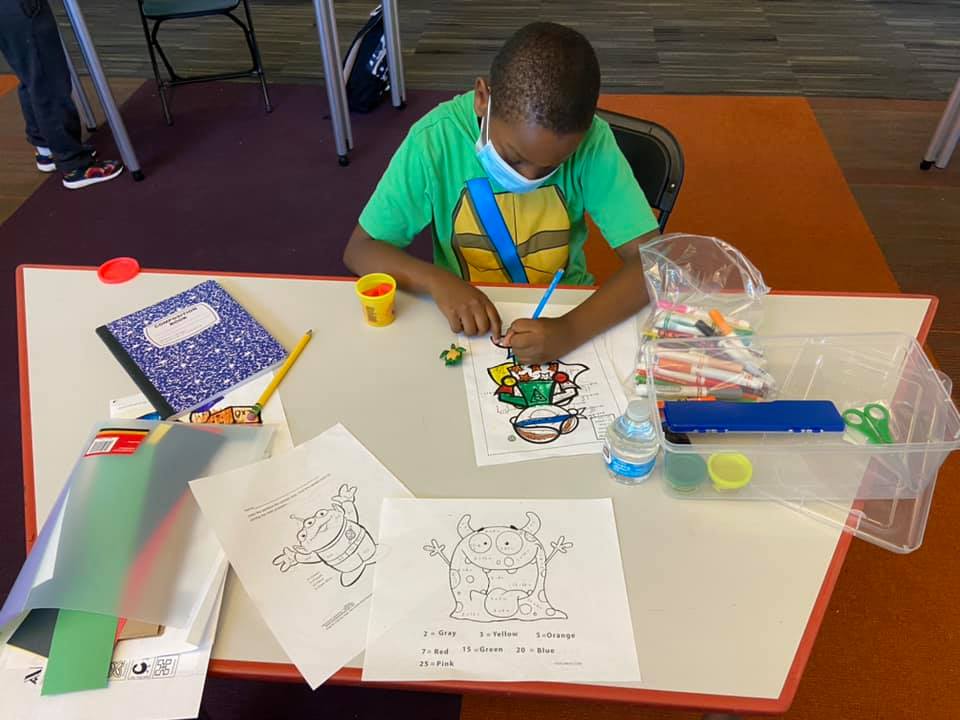

EOYDC is a nonprofit organization that provides after school and summer programs focusing on academics, art, education, wellness, and career development for youth ages 5 to 24. The organization calls itself a “home away from home” and “an oasis in the desert of inner city life” and “the pathway to a brighter future.”

EOYDC is located in a low-income, high-crime area of East Oakland, and many of its youth participants have experienced complex stress and trauma. The organization’s approach is trauma-informed and healing-centered, but staff there knew that some of the youth they worked with needed even more support, and thought the partnership pilot would be a good way to explore partnerships to achieve that goal.

In July and August, 2019, CCI staff met with Selena Wilson, EOYDC’s vice president of organizational effectiveness, and Landon Hill, director of program effectiveness, and other EOYDC staff for planning and work sessions to brainstorm the scope of the pilot and develop concrete goals using human-centered design tools. Wilson and Hill had previously participated in Catalyst training, and routinely incorporate human-centered design practices in their work with young people. “These tools were extremely helpful during our initial brainstorming sessions,” says Hill.

EOYDC’s initial question, which they developed during the brainstorming sessions with CCI, was: “How might we create a warm network of support to connect youth to behavioral health services and healing-centered resources in East Oakland?”

But as these discussions progressed, EOYDC realized they needed to back up a step and look even closer to home. Their goal was to promote healing among their youth participants and in the broader community. Before they could pursue these goals, however, they realized they needed to know more about their families and communities and the challenges they face. They decided to reach out to the parents in their community to learn more about their lives and to find out what healing means to them. “We have good relationships with our parents,” explained Landon Hill. “But we really know the kids because we see them every day. We realized we don’t know much about what’s going on at home, or much about the issues our parents are facing.”

This realization led to more brainstorming about how to engage parents. CCI helped EOYDC staff strategize about how to engage parents and help them feel ownership in the process. “We didn’t want to just talk to parents,” says Hill. “We wanted to figure out a way to collaborate with them and find out how we can best support them. And we wanted to give them agency to lead the process.”

Parents as Partners

Our families are the best! They show up for the @eoydc parent night scep turnup! #youthledsummer pic.twitter.com/ptZmU5jHw3

— Regina Jackson (@reginaoak) March 8, 2020

Hill and Wilson decided the best way to engage parents was to start a parent working group. They began reaching out to parents to find out if they were interested in participating. Partnerships, it turns out, can take many forms: unlike the LSC+USC pilot, which was between discrete organizations, EOYDC’s created partnerships with parents, who are key stakeholders in the community.

In September and November 2019, EOYDC hosted several parent dinners with funding and planning support from CCI, where parents got the opportunity to share their experiences and concerns. In the process, they introduced the idea of establishing an ongoing parent working group and gauged the parents’ interest.

Hill says the discussions at the meetings were productive. The participants were enthusiastic about the idea of an ongoing parent working group. Some of the concerns and needs they identified included:

- More male mentorship for youth.

- Extended youth programming on the weekends and in the summer.

- Safe transportation options from school to EOYDC.

- Neighborhood improvements to create safe spaces for young kids and teens to gather and build community.

Parents also expressed a desire for more family support and mental health services for their children.

“These were important insights for us,” said Hill. “We realized we didn’t know how parents were thinking, what’s working for them and what isn’t. We wanted to learn from them, to step back and give them a voice and a space where they could express that voice.”

Wilson and Hill returned to their human-centered design training again and again throughout the process. “Collaboration is an important human-centered design concept, and of course that helped guide our thinking as we developed the partnership with parents,” says Hill. “We also introduced some human-centered design tools in our [most recent] meeting with parents, particularly the brainstorming strategies. We planned to introduce more of the tools in our next session but didn’t get far enough along in the process. This is definitely something we’ll get back to when our parent working group gets together again. We’d like to get to the point where the parents can use the tools themselves.”

EOYDC staff informally referred to the parent working group as the “Parent Village” but they wanted the parents to choose a name for their group themselves. “That’s one of the things we talked about at our last meeting: what they wanted to call the group,” Hill recalled. “And then the pandemic hit, and shut everything down.”

Lockdown and Beyond

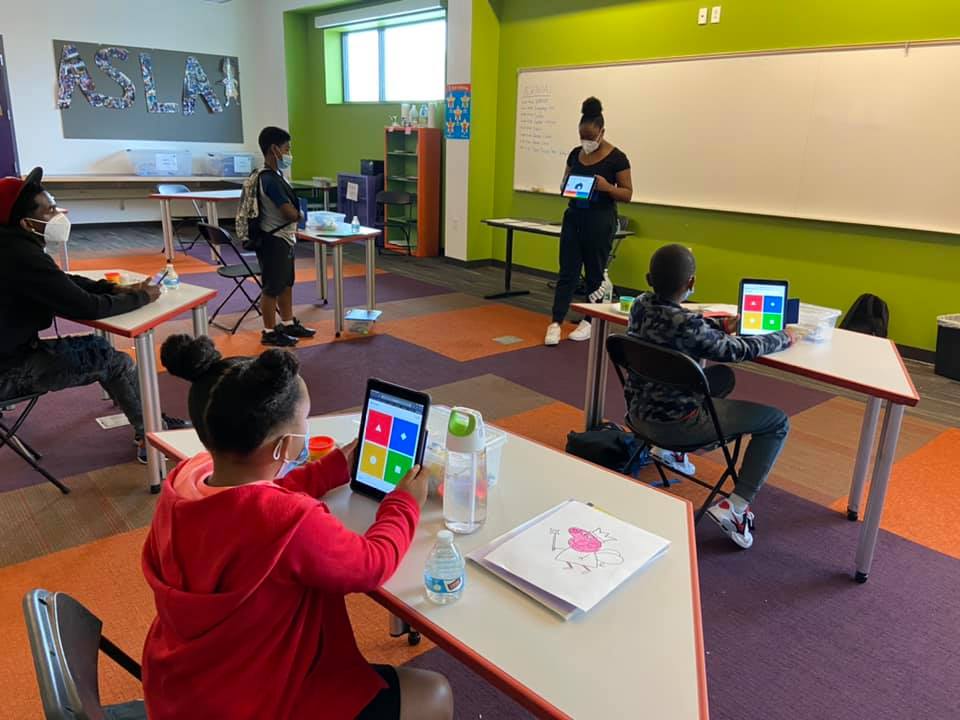

There have been no more parent gatherings since the pandemic, and Hill says that, while EOYDC intends to resume the meetings in the future, there are no immediate plans to do so. This is due in part to limited organizational capacity. EOYDC was closed for in-person activities from mid-March to late June (they offered virtual programming for that entire period) when they opened again. Now they are running an all-day on-site program where kids attend school online, and participate in enrichment activities when the school day is over.

There have been no more parent gatherings since the pandemic, and Hill says that, while EOYDC intends to resume the meetings in the future, there are no immediate plans to do so. This is due in part to limited organizational capacity. EOYDC was closed for in-person activities from mid-March to late June (they offered virtual programming for that entire period) when they opened again. Now they are running an all-day on-site program where kids attend school online, and participate in enrichment activities when the school day is over.

“So much of our time since the pandemic has been ensuring that our on-site programs are meeting health protocols,” says Hill. “We’ve had to put in a lot of effort meeting CDC guidelines and making sure the environment is safe for students to participate. We’ve also been working hard to ensure that students keep up with their school work and participate in enrichment activities too.”

Practical issues posed by the pandemic have also put the parents’ working group on hold. In order to limit infection risk, no visitors, including parents, are permitted on site. Hill says EOYDC staff have been considering holding parent meetings via Zoom, but need to figure out how many parents have access to the appropriate technology to make remote meetings feasible.

What’s Next

“The need for EOYDC was great before the pandemic, and now the need is enormous.”

-JR Valrey ( EOYDC ALUM)

We are happy to serve our community today, tomorrow and into the future!!!!! #motivationmonday https://t.co/zjVlAsCbGK— EOYDC (@eoydc) August 3, 2020

Still, for Hill and the rest of the EOYDC staff, the partnering project has been a valuable experience and they intend to start it up again as soon as possible. “We have a lot of new students, so we want to identify new parents who are interested in joining the working group,” Hill said. “We also want to know how parents are dealing with job loss, fears about their children physically returning to school, and all the challenges families have had to face over these last months. We don’t know exactly what it will look like but we know there will be a reset. The parents in our group were developing some camaraderie, but that process may have to start all over once the group is up and running again.”