![]() Once the decision to integrate telemedicine into routine care delivery is made, frontline care teams must begin to deliver telemedicine efficiently, safely, and equitably.

Once the decision to integrate telemedicine into routine care delivery is made, frontline care teams must begin to deliver telemedicine efficiently, safely, and equitably.

The key considerations for frontline teams include:

- Provider and team devices,

- Developing telemedicine visit workflows,

- Ensuring care visit quality and safety, and

- Supporting staff and team well-being.

→ Want a more searchable and tagged version of this toolkit? Check out the Virtual Care Learning Hub!

Provider and Team Devices

Telemedicine requires internet-connected devices with a camera, microphone, and speakers. These range from smartphones to tablets to computers. There are several key challenges with provider devices. The privacy and security considerations for health care settings are discussed in the chapter of this toolkit devoted to privacy and security. For offsite clinicians, there are specific considerations for telemedicine delivery. Many health care teams use personally-owned devices to deliver or participate in telemedicine workflows. The resources below address common general provider- and system-facing challenges, as well as ones that have emerged as a result of the enforcement discretion during the pandemic. Main recommendations for improving cybersecurity for provider and team devices include using encrypted technology, utilizing a virtual private network (VPN), and employing strong authentication parameters.

- American Medical Association: Checklist: Protecting Office Computers in Medical Practices Against Cyberattacks — This PDF lays out privacy and security practices for physicians using their own computers for telemedicine, and it provides guidance on fundamental practices such as account and password management, updates to browsers and operating systems, and anti-virus measures.

- American Medical Association: Working from Home During COVID-19 Pandemic — This PDF offers advice for personal smartphones and tablets, including use of electronic medical record-associated and telemedicine vendors’ mobile applications.

- Rural Health Information Hub: Telehealth Use in Rural Healthcare — Funding & Opportunities — This webpage gathers funding opportunities for rural health care centers using telemedicine. These include grants to promote planning and development, implementation, and enhancement of telemedicine programs, including potential device support. The Rural Health Information Hub also includes a Rural Telehealth Toolkit with modules on program models, implementation, evaluation, program sustainability, and dissemination. The implementation module includes this PDF from the California Telehealth Resource Center. Page 23 of the PDF includes a useful table outlining the step-by-step process of developing a telemedicine marketing plan, including sample questions for patient, clinician, and administrator satisfaction surveys.

Health Care Team Workflows

Staff Roles. Telemedicine necessitates multiple new staff roles and workflows, including program management, site coordination, clinical oversight, technical support, and more. It is critically important to build in staff expertise and adequate time for patients with varying levels of digital literacy to successfully join and participate in telemedicine visits. Many clinics are experiencing a higher visit volume with telemedicine and scheduling should account for this higher show rate. During a visit, it is critical that each team member know their role and the needed electronic medical record documentation practices.

- California Telehealth Resource Center: Telehealth Program Developer Kit — This PDF lays out the staff roles needed for successful telemedicine implementation in the “Staffing” section beginning on page 161.

- American Academy of Family Physicians: A Toolkit for Building and Growing a Sustainable Telehealth Program in Your Practice — This PDF provides a comprehensive guide to developing and improving a telemedicine program. Starting on page 16 it outlines a framework for approaching telemedicine staffing and roles, and starting on page 32 there is a section on documentation and consent requirements, including a sample patient consent form for staff to use with patients.

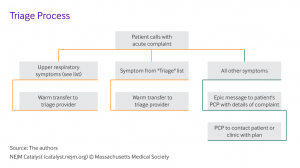

Scheduling and Triage. Determining whether telemedicine vs. in-person care is more appropriate, is the first step in carrying out new telemedicine workflows. The resources below offer guidance on how to approach scheduling and triage with a telemedicine system in place.

- Health Information Evaluation and Quality Center (HITEQ): Getting a New Workflow and Process Started During COVID-19 Pandemic — This is a link to download a PDF with information about getting a new workflow and process started during the COVID-19 pandemic. This guide includes a section called “Come up with a triage plan” on page 3, which outlines the key steps to determining which patients should be seen in the office and which should be seen via telemedicine.

- New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst: Seeking Evidence-Based COVID-19 Preparedness: A FEMA Framework for Clinic Management — This article includes decision-making flowcharts to assist in scheduling decisions.

- American Academy of Family Physicians: A Toolkit for Building and Growing a Sustainable Telehealth Program in Your Practice — This PDF provides a comprehensive guide to developing and improving a telemedicine program. Starting on page 19, it includes a section on determining telehealth appropriateness, including a list of considerations for determining when telehealth vs. in-person care is better. Also, starting on page 25 there is a section on scheduling, including sample scripts to use when scheduling and confirming telemedicine appointments.

Workflows. Delivering high-quality, equitable telemedicine care requires new workflows and protocols. Transitioning team-based workflows from in-person care to telemedicine is an ongoing challenge, and many health care settings are currently experimenting and innovating on how to do this well. The resources below offer real-world examples of how various health systems have approached these aspects of telemedicine implementation, including several examples from public and FQHC sites specifically.

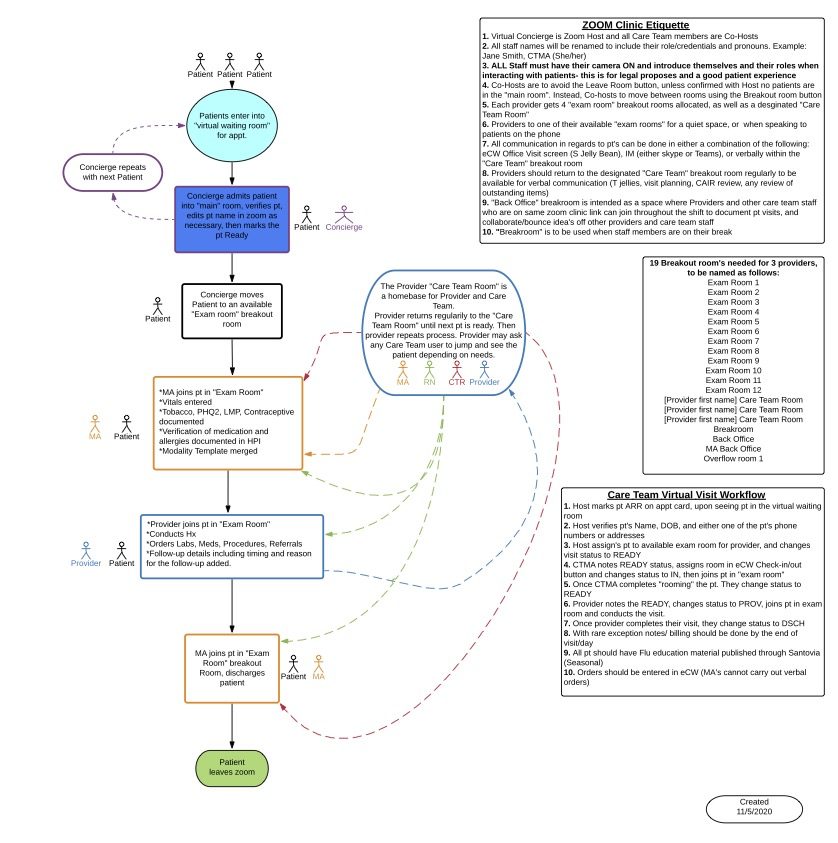

- West County Health Centers: Virtual Clinic Workflow Using Zoom Breakout Rooms — This workflow provides a “virtual clinic layout” for care teams using Zoom breakout rooms for telemedicine. It includes descriptions of different administrative and clinical team members’ roles in managing a Zoom clinic, from patients’ first check-in through the telemedicine visit itself and discharge. This tool was created by West County Health Centers — a Federally Qualified Health Center offering comprehensive medical, dental, behavioral health, and other specialty services to the communities of western Sonoma County, California — as part of their work through CCI’s Connected Care Accelerator.

West County Health Centers

- Petaluma Health Center: Tech Volunteer Workflow — This is a workflow for volunteers providing tech assistance to patients prior to their telemedicine appointments. It includes steps such as checking whether patients have email addresses, eClinicalWorks patient portal access, and the Healow and Webex apps, and completing appropriate consent documentation. This tool was created by Petaluma Health Center — a Federally Qualified Health Center offering comprehensive medical, dental, mental health, and specialty care services for communities in Petaluma, California — as part of their work through CCI’s Connected Care Accelerator.

Petaluma Health Center

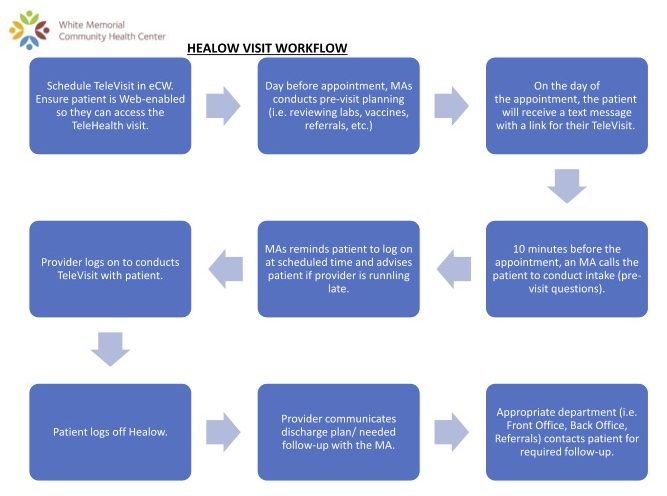

- White Memorial Community Health Center: Video Visit Workflow — This is a workflow for scheduling and completing a video visit using Healow, an application from eClinicalWorks. It includes steps such as ensuring patients’ web accessibility, conducting pre-visit planning, sending text message reminders, and following up with patients after the visit. This tool was created by White Memorial Community Health Center — a non-profit health center in Los Angeles, California that provides primary healthcare services to children, adults, and seniors regardless of patients’ ability to pay — as part of their work through CCI’s Connected Care Accelerator. To learn more about how White Memorial improved video visit infrastructure and assessed patient satisfaction with telemedicine, check out this case study.

White Memorial Community Health Center

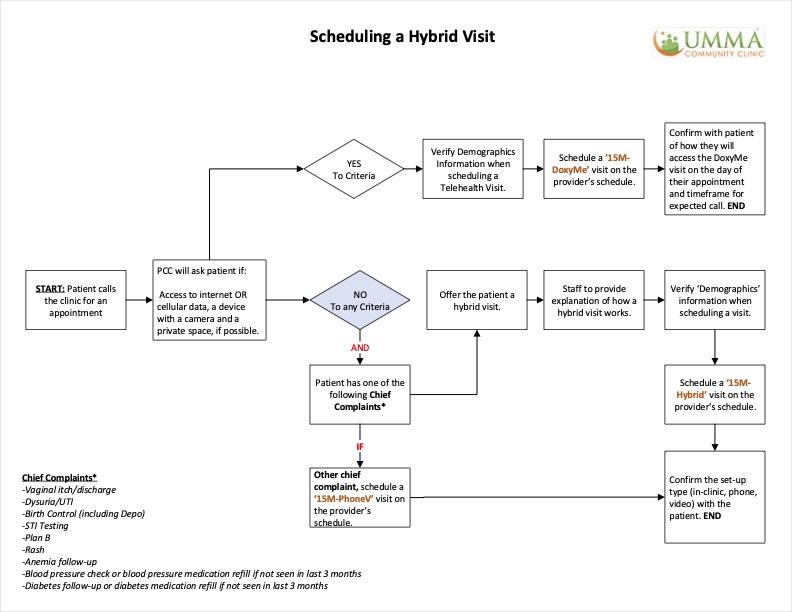

- UMMA Community Clinic: Hybrid Visit Workflows — This collection of three workflows provides guidance for scheduling, confirming, and completing hybrid visits using Doxy.me and eClinicalWorks. Some sites have found hybrid visits useful if patients need to come on-site in order to access the internet, devices, or private space needed to complete a video visit as well as to access specialty care that may not be accessible locally. This tool was created by University Muslim Medical Association (UMMA) Community Clinic — a Federally Qualified Health Center and Patient Centered Medical Home in Los Angeles, California providing medical, behavioral health, educational, and other services to promote the wellbeing of the underserved, regardless of ability to pay — as part of their work through CCI’s Connected Care Accelerator

UMMA Community Clinic

- Center for Care Innovations: How San Mateo Medical Center (SMMC) Harnessed All Care Team Members to Streamline Telemedicine Workflows — This case study describes how San Mateo improved their telemedicine workflows by streamlining virtual “warm handoffs” between team members during telemedicine visits and incorporated social determinants of health screening into their standard telemedicine workflows.

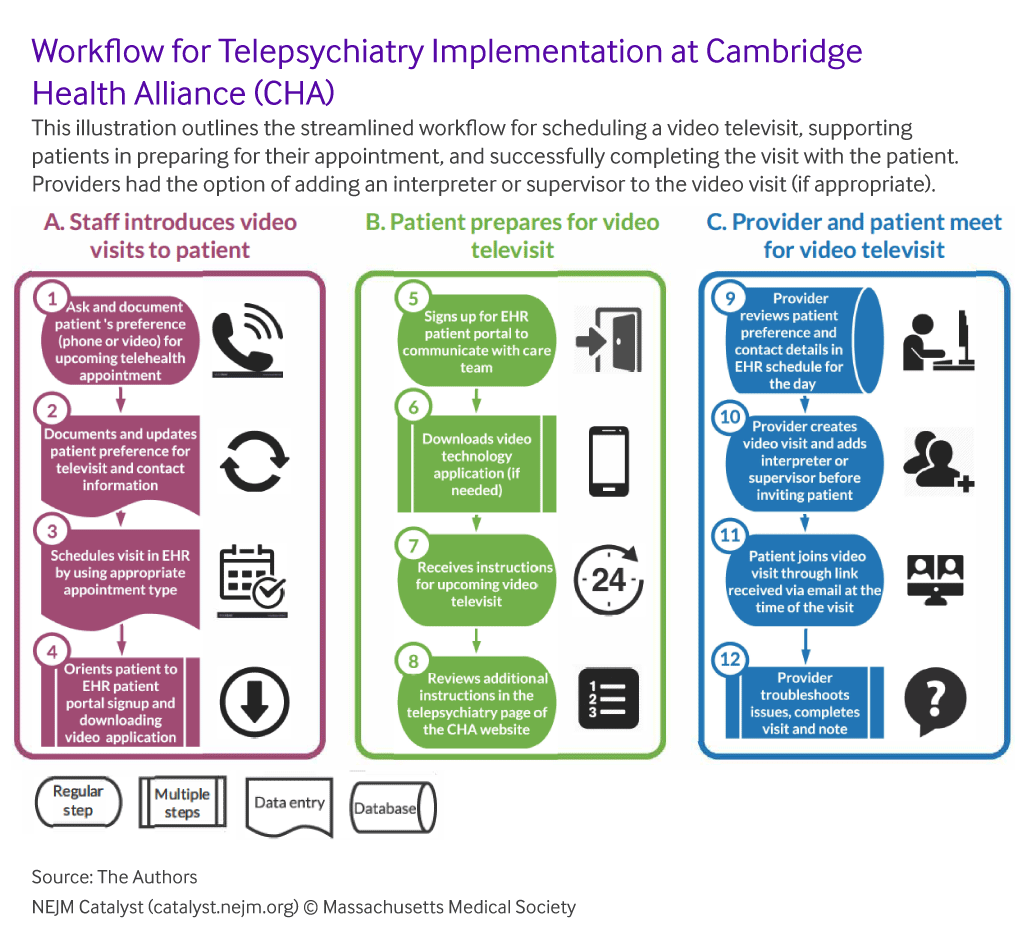

- New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst: Rapid Implementation of Telepsychiatry in a Safety-Net Health System During Covid-19 Using Lean — This article provides a breakdown of applying the LEAN quality improvement approach to rapidly implement telepsychiatry in a safety-net system, including reports of hours invested per role, detailed workflows, and examples of PDSAs to apply a quality improvement approach to your setting.

- Care Oregon (Medicaid health plan): Telemedicine Technical Assistance Guide — This PDF provides guidance on what can be treated by telemedicine starting on page 2 (video, phone and e-visits). Starting on page 8, there is information about how to integrate phone and video visits into workflows. There is also guidance around telemedicine for integrated behavioral health.

- Center for Care Innovations: Telehealth and Telephone Visits in the Time of COVID-19: FQHC Workflows and Guides — This article has sample visit and documentation workflows for switching from in-person to telephone and video visits developed by FQHCs using Nextgen and eClinicalWorks electronic health record systems. These include pre-visit patient reminders with English and Spanish versions of a script, team member call initiation, intake, and clinician documentation.

- Mid-Atlantic Telehealth Resource Center: Sample Telehealth Policies and Procedures — This PDF includes real-world example workflows and protocols for telemedicine implementation.

- UCSF Center for Vulnerable Populations: Resources for Telehealth at Safety Net Settings — This webpage provides resources for telehealth in safety net settings. The section “For Clinicians” includes a link to download a word document “Quick guide to your first telehealth visit” for clinicians using Zoom, with documentation guidelines that are not specific to any electronic medical record.

- Epic: Telehealth and Remote Care to Combat COVID-19 — This webpage is about how telehealth and remote care are being used to combat COVID-19. At the bottom of the page there is a link to a white paper, accessible if your organization uses Epic, called “Managing Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) With Epic” which is updated regularly with recommended build and workflows. In addition, there is a link to a webinar from Epic’s telehealth team, also accessible if your organization uses Epic. If you have trouble accessing these resources, you can contact [email protected].

Conducting Safe and Appropriate Telemedicine Visits

Diagnostic Safety Considerations. Many clinicians may have concerns that with telemedicine, they may make an incorrect diagnosis or miss a clinically important finding leading to an adverse event. Patient follow-up during the COVID-19 pandemic is also variable, and it may be more challenging to obtain recommended labs or other testing needed for a correct diagnosis. Evidence has shown that telemedicine has similar diagnostic accuracy as in-person visits for common conditions, though if uncertainties or red flags arise, appropriate triage and referral to in-person care is important.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Telediagnosis for Acute Care — This PDF issue brief, released in August 2020, discusses implications of telemedicine on the quality and safety of diagnosis.

- Telemedicine Journal and e-Health: How Accurate Are First Visit Diagnoses Using Synchronous Video Visits with Physicians? — This article about telediagnosis compares the diagnostic precision in telemedicine encounters and in-person encounters. The authors find that telemedicine diagnostic accuracy has high correlation with in-person diagnoses.

- International Journal of Emergency Medicine: Telemedicine in Pre-Hospital Care: A Review of Telemedicine Applications in the Pre-Hospital Environment — This review article looks at telemedicine use in emergency medical or pre-hospital care settings. The authors find that telemedicine improves the timeliness of stroke and myocardial infarction diagnosis and treatment.

Clinical Assessment. The following are some suggestions and strategies for providers to ensure you are assessing and diagnosing conditions as safely as possible via telemedicine services and continuing to provide patient-centered care. Reviewing best practices prior to your first telemedicine visit is an important starting place.

| A telephone or video encounter enables clinicians to gather the same SUBJECTIVE information as an in-person encounter (history of present illness, past medical history, etc). In fact, the medication reconciliation may be more accurate as the patient can review their pill bottles at home. For OBJECTIVE information, a patient may be able to check their own temperature, blood pressure, and pulse if they have home equipment, and can often palpate areas of the body or test range of motion with your instruction. With this information, be systematic in formulating a differential diagnosis and recognize that a remote context means your differential may be broader — avoid “premature closure,” meaning narrowing or finalizing a diagnosis too early. | National Telehealth Technology Assessment Resource Center: Video Platforms: Clinical Considerations — This webpage has information and a video outlining clinical considerations to keep in mind when using video platforms. They advise, “When a clinical provider is presented a patient.., we inherently consider the information that we have been able to collect and the differential diagnosis of possible conditions….In the setting where the interaction is limited by video, audio, or a textual presentation, it simply means that we are unable to remove some items off the differential when compared to those we may have comfortably removed when seeing the patient in person, or a different setting.”

Mid-Atlantic Telehealth Resource Center: Telehealth Resources for COVID-19 — Within the “Best Practices for Conducting a Telehealth Visit” section of this webpage, there are resources on “Clinical Assessment and the Physical Exam,” including a series of videos on conducting physical exams via telemedicine. In addition, the “Other Useful Implementation Resources for Clinicians and Practices” (also within “Best Practices for Conducting a Telehealth Visit”) has links to specialty-specific resources on clinical considerations for providing care via telemedicine. |

Promoting Telemedicine Provider Well-Being

In times of crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic, burnout among those providing telemedicine is a serious concern. Telemedicine providers working remotely may lack the opportunity to check-in with colleagues, team members, or supervisors, resulting in feelings of isolation. In settings where a high proportion of patients have digital and health literacy challenges, the high prevalence of technical problems during telemedicine visits can exacerbate feelings of burnout. The loss of in-person care and dramatic increase in screen time has been called “Zoom fatigue” or “telemedicine fatigue,” and is uniquely physically and cognitively taxing. If you’re feeling this, you’re not alone.

- American Psychiatric Association Foundation Center for Workplace Mental Health: Working Remotely During COVID-19: Your Mental Health & Well-Being – This PDF includes suggestions to help health care providers maintain mental health and well-being while working remotely during COVID-19.

- Center for Care Innovations: Supporting and Empowering Team Members and Patients During COVID-19 — This webinar emphasizes that self-care among health care providers is essential, encouraging mindfulness such as meditation techniques to stave off compassion fatigue.

- Telebehavioral Health Institute: Zoom Fatigue—What You Can Do About It — This blog post includes some tips on recognizing and addressing “Zoom fatigue” arising from increased telemedicine use.

Telebehavioral Health Institute

Find this useful or interesting? We’re constantly sharing stuff like this. Sign up to receive our newsletter to stay in the loop.