Project Activities

Project Activities

Focus on food insecurity

A number of factors made a focus on food insecurity logical. For one, county data indicated that as many as one in three of NEVHC’s patients were at risk for food insecurity. Additionally, the organization had accumulated a substantial amount of knowledge in this area through participation in various programs and initiatives designed to address the food needs of the wider community. Focusing on the single domain of food insecurity also allowed the project team to bite off a manageable project that aligned with the Champions of Change grant and an Los Angeles County push for countywide food insecurity screening.

Project site and population

To efficiently screen and document food needs, the team decided to take advantage of an existing pilot of patient-facing tablet computers that were being used for PHQ9 screening with pediatric patients, ages 12 to 17, in two health centers. The tablets, from a company called OTech, interfaced with the health system’s electronic health record, NextGen, for efficient data collection.

Food insecurity screening tool

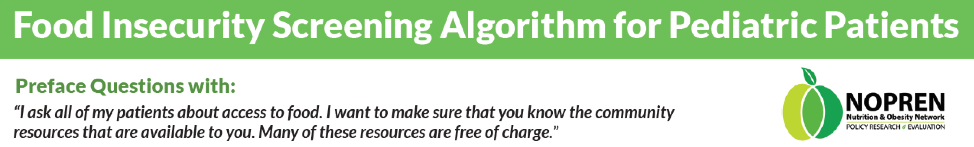

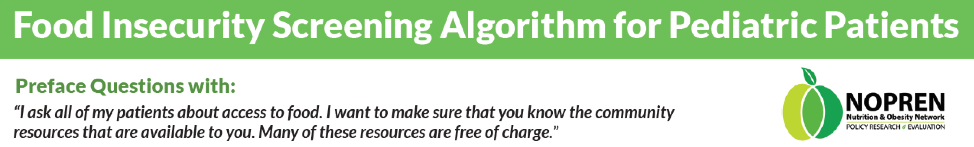

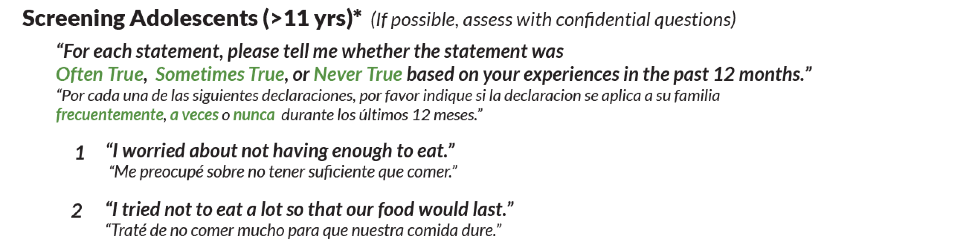

The ROOTS team utilized the adolescent version of the Hunger Vital Sign, a two-question food insecurity screening tool, developed by the Nutrition and Obesity Network (NOPREN):

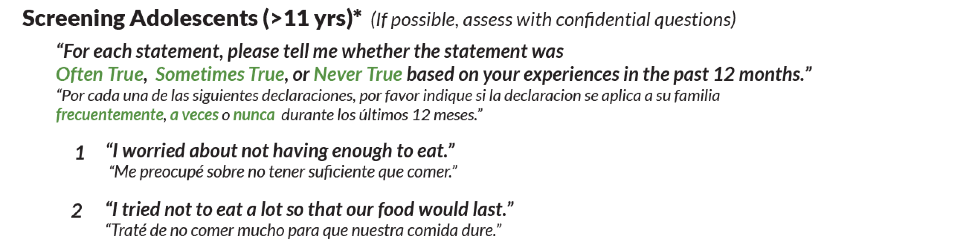

Provider response algorithm

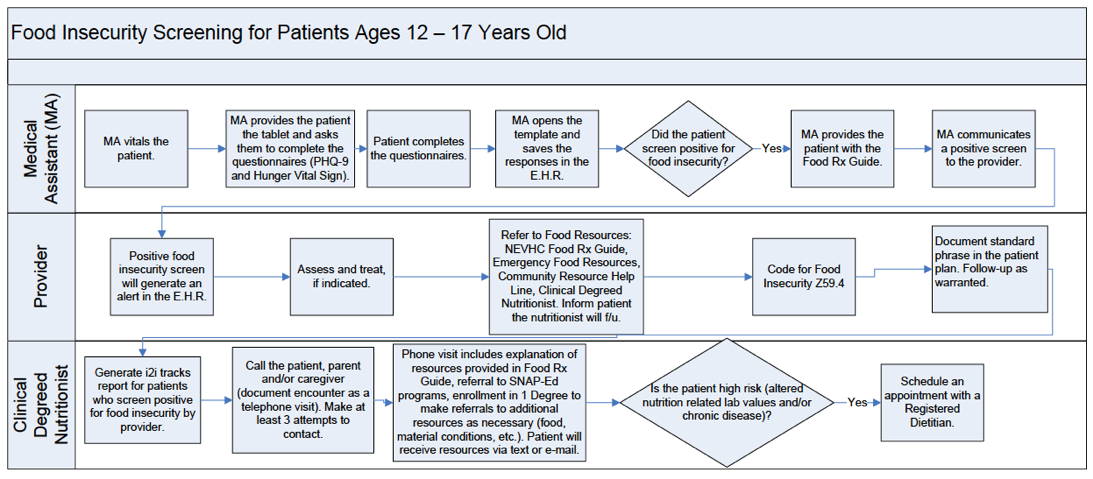

To screen patients, medical assistants handed patients the OTech tablet and explained the survey during well-child visits. The youth were encouraged to complete the screening on their own, but they could also ask parents for help if needed. Providers then responded to positive screens with clinical assessments, education, referrals, and documentation.

Implementation challenges and adjustments

Although the Hunger Vital Sign has been validated against a set of 18 questions developed by the United States Department of Agriculture to measure food insecurity, the NEVHC team found that a number of their young patients misinterpreted the questions to be about whether they were allowed to eat the foods that they most wanted to eat. In other cases, the youth would screen positive, but when the provider discussed this with the parents, they would say that was not the case, possibly because they did not want to admit to struggling to feed their family. The NEVHC team addressed this by being empathetic and trying to de-stigmatize food insecurity.

Initially, the ROOTS team envisioned that patients who screened positive for food insecurity would receive resource referrals during the patient visit through One Degree, an online community resource referral platform that NEVHC accessed using ROOTS grant funds. However, it quickly became clear that care teams did not have time during visits to both review the assessment and explain how to use One Degree. The project team therefore decided to have the care teams focus on empathetically addressing positive screens and briefly explaining food resources available to patients. Then, after the visit, a community health worker or nutritionist would follow up with patients who screened positive for further assessment, referrals, and to introduce One Degree. This workflow has worked much better.

With One Degree, patients receive referrals for community-based resources related to non-medical needs like food, housing, and transportation. The health system can track referral outcomes reported by patients and referring agencies.

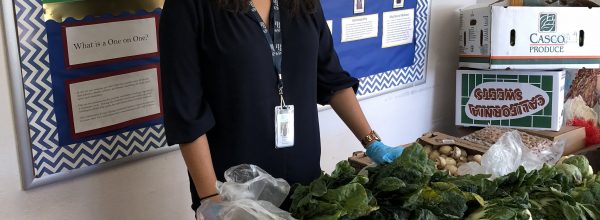

Tailoring resource referrals

Focus groups revealed that patients were unfamiliar with the term “food pantry” and believed that one food bank gave out “bad food” because they were past sell-by dates. By visiting food pantries, the team also learned that many of the available foods were unfamiliar to their patient population. To help patients understand resources available to them, the team developed a comprehensive educational Food Rx Guide that includes contacts for local food pantries (which the team relabeled as “free groceries”), meal plans and recipes, information about “sell by” vs. “safe for consumption” dates, and details about NEVHC nutrition classes and programs. The guide also explains how to access One Degree. Care teams now hand out the Food Rx Guide during well child visits. The team also started offering monthly nutrition workshops, where they explain available food resources and connect patients to a community health worker-led resource help line and SNAP benefits (i.e., Calfresh/food stamps and WIC).

Technological challenges

A primary goal of the NEVHC ROOTS project was to use technology to maximize efficiency of collection of social needs data and referrals for services. However, the technology ended up posing its own set of challenges.

First, the OTech tablets were losing their battery charges too quickly. Replacement tablets resolved these issues, but the pilot was delayed. Second, to function, the tablets had to connect to the internet, however, Wi-Fi service within the clinic was spotty. A Wi-Fi service upgrade partially helped address this issue, although there are still areas in one of the clinics where the tablets cannot be used. The NEVHC project team have decided to stick with the OTech tablets, which had been previously deployed in another screening pilot, because as they felt the tablets were only worth using if they could accommodate multiple screening tools.

Finding the time to train the care teams on how to use the technology was also a challenge. Providers usually required one-on-one training, which was difficult to schedule, especially with staff turnover and the use of per-diem providers. The project team found that delegating most of the screening to medical assistants and creating an automated referral process through the use of the population health management tool, i2i tracks, was the most effective.

Impact

Despite the implementation challenges, staff and leadership responded favorably to the pilot. Patient satisfaction surveys also showed that children and caregivers were open to care teams asking them about and addressing non-medical needs. Additionally, the project raised awareness systemwide about how food insecurity impacts NEVHC patients.