How can we break down the silos that wall-off schools, clinics, and families from each other?

Santa Cruz Community Health Centers (SCCHC) and the Live Oak School District are collaborating to improve health and educational outcomes through a Community Care Team — a cross-sector partnership that brings together pediatrics, behavioral health and child psychiatry with teachers, the school nurse, and school counselors.

Thanks to a grant from our Innovation Lab, they’re testing this comprehensive support and treatment for 15 high-risk, high-need children at Live Oak Elementary School. The goal is to fundamentally change the relationships between families, their health care providers, and schools.

The Problem

Live Oak is an unincorporated community and “census designated place” located between Santa Cruz and Capitola in Santa Cruz County, California. Despite the fact that the community is only 3.2 square miles, 17,400 people live in Live Oak. It has a large population of Latinx immigrants. And like so many California cities, families are grappling with exorbitant housing costs.

Because of the demographics, size, and density of the community, Live Oak School District struggles with many of the challenges that face large urban school districts.

For instance, a number of high-risk, high-need children attend Live Oak Elementary School:

- 25 percent are homeless

- 59 percent are English language learners

- 76 percent are low income

- Half of third graders are proficient reading at grade level

- 60 percent of low-income fifth graders have adequate fitness for good health, as measured by a state program that tests aerobic capacity, strength, body composition, and flexibility.

To meet the challenges associated with these demographics and a desire for better outcomes, SCCHC and the Live Oak School District have sought out new ways to strengthen the schools and community.

Together, they identified one major obstacle: the lack of ongoing, effective communication between parents, educators, and health care providers when problems arise. In fact, institutional silos were actually preventing them from sharing information and coordinating services to support these children.

The Solution

SCCHC, the Live Oak School District, Live Oak Cradle to Career, and Live Oak parents created the Community Care Team, which engages parents and school-clinic partners to identify, treat, and monitor high-risk, high-need students.

The Community Care Team operates through two communication channels:

Two-Way Communication Line

The school and SCCHC opened up a bidirectional line of communication to better facilitate regular, open collaboration. The goal was to also provide “warm hand-offs,” or personal transfer of care, between the school and clinic.

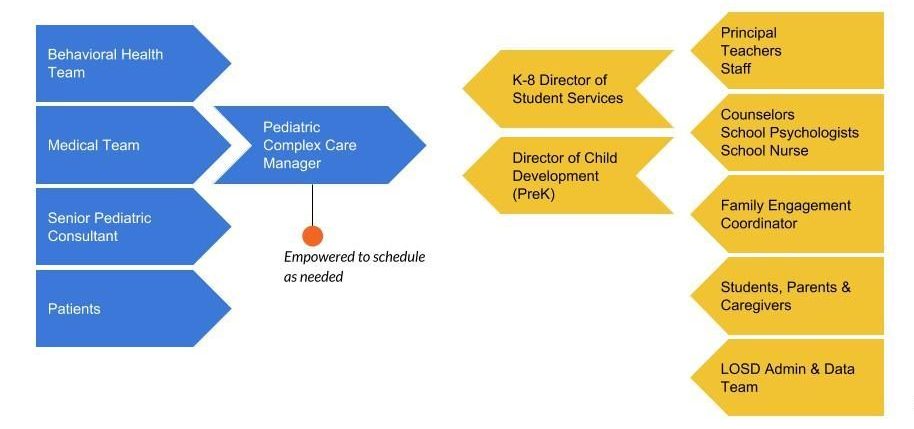

The clinic’s point person, the Pediatric Complex Care Manager (a PhD Nurse Practitioner), and the school’s point people, the Director of Student Services and Director of Child Development, are in constant contact. The goal is to schedule calls at least twice a month, but in reality, they often call and text each other whenever the need arises.

Because of this two-way communication line, they can:

- Triage clinical needs, such as referring a student or parent to a behavioral specialist.

- Schedule same-day clinic visits.

- Create joint Individualized Education Program (IEP) and medical appointments.

- Hold joint family-school-clinic conferences

Case Conferences

Case conferences are in-person meetings of clinic and school providers. Every other month, they come together to share information, including voice recordings of parents expressing their hopes and concerns, to piece together the behavior and experiences of a particular child. This cross-sector group then identifies systems-level solutions and develops a shared care plan.

This care plan is unique in that it includes educational details that previously would have been inaccessible to pediatricians. And it includes clinical advice that would have been previously unavailable to school personnel.

So far, case conferences have focused on parental wellness and the treatment and educational placement of a child with autism. Satu Larson, the Pediatric Complex Care Manager, recently shared this success story during a recent presentation of her team’s project:

The case conference focused on a child who had been exposed to methadone in utero. He was successfully weaned with morphine, and at 3-years-old, when his mother relapsed, he was fostered and adopted by his grandmother. While in the foster system, the child was sent to Stanford University’s neurodevelopmental clinic and then referred to the county behavioral services to treat hyperactivity. From age of 4, the child has tried differing classes of medications (non-stimulant, sedative, SSRI, antipsychotics).

His grandmother had been bringing him to the clinic more frequently because of aggressive behavior, violent thoughts, and expressions of self-harm. His biological mother and father had re-entered his life and the grandmother felt the child was struggling both at home and in school. Yet, when the provider asked the child how he felt on the current medication, he reported feeling “calmer, more in control.”

The case conference brought stakeholders from the school (teachers, school counselors, school psychologist, the principal, director of student services), the clinic (pediatrician, complex care manager, lead behavioral health provider, behavioral health coordinator, CEO), and a Stanford partner (developmental behavioral specialist).

It opened with a brief history from each group. Then the group played the audio recording of mother and grandmother describing their hopes for the child, as well as how they would like the group to help them. From this point, the floor was open for discussion.

The group learned from teachers that clear rules and expectations in a safe environment had created conditions in which the child thrived. The school did not witness any aggressive behavior or expressions of self-harm. In fact, the child got along well with his peers. This insight gave the pediatrician a new lens with which to understand his patient’s needs. Rather than creating a medical solution, what was needed was greater support for the parents and grandmother to provide the successful structure at home that their son was benefiting from at school.

After the conference, the primary care provider and the special day education teacher created a care plan, then shared it with the family. The clinic was able to initiate family therapy services. The mother reestablished care at the clinic for herself, seeing a behavioral health care provider to address her own childhood trauma; after four appointments that focused on parenting and social skills, the child is now less aggressive at home and appears to be happier.

Today’s Takeaways

- Open the doors, not the floodgates: Facilitating an organized flow of communication between school and clinic partners has been essential to surfacing, filtering, and relaying information while not overwhelming either party.

- Start with what you’ve got: Jumping in and learning while doing is helping the team better understand what is needed to grow this model.

- Parent engagement is essential: Every case has revealed how crucial family dynamics are to the wellbeing of children. In cases of very high-need families, parents often no-show for appointments and struggle to follow through on referrals. The team is now looking to hire a bicultural, bilingual LCSW/RN who can meet these parents where they are at and hold their hands on the path to healing.

- Don’t underestimate costs. Innovations that transform health and education in this way are both essential and expensive. Policymakers, funders, payers, and health, social service, and education sectors must be prepared to invest in such transformation to make this helpful integration permanent. Healing childhood trauma so that it doesn’t transfer to the next generation is complex – but crucial – work.

- Build relationships: “This has been many years in the making, forming trust between school and clinic partners. It’s now so magical to get everyone together to start sharing information and working together,” said Allison Guevara, the SCCHC’s social impact consultant.

Next Steps

- Systematically ID struggling students: Currently, the Community Care Team relies on the Director of Student Services to zero in on the students with the greatest needs. The team wants to be more methodical, so it can better identify struggling students who may not be as loud. SCCHC is working with the school to start tracking risk factors through its software, Illuminate Education. It’s looking at attendance (chronic absenteeism, tardiness), school behavior (office referrals, school nurse visits), academic performance, and family satisfaction. At the same time, the team is mindful about taking the negative bias out of these metrics, so the school isn’t building a record that follows a “bad kid.”

- Electronic data sharing: The school and clinic are currently working on a legal agreement that will eventually allow both parties to share information electronically — and help scale this project beyond the initial cohort of 15 children. Then the next hurdle is to find case management software that will facilitate this up-to-the-minute flow of information.

- Continue building clinical and educational teams: These teams are critical to increasing the number of families served and ensuring appropriate pathways that address the range of needs that emerge from this multidisciplinary model.

Learn More

Find this useful or interesting? We’re constantly sharing stuff like this. Sign up to receive our newsletter to stay in the loop.