Healing a Community — One Student at a Time

A significant body of research has established a clear link between income and health. According to A Portrait of Marin, a 2012 study by the American Human Development Project: “The world over, health follows what is known as a social gradient: people of higher socioeconomic status, as measured by indicators such as occupational prestige, level of educational attainment, and income, have better health, on the whole, than people of lower socioeconomic status—and the effect is seen not just at the extremes, but at every step along the social ladder. People of lower socioeconomic status die at a higher rate than others from nearly every cause.”

In other words: poverty makes people sick.

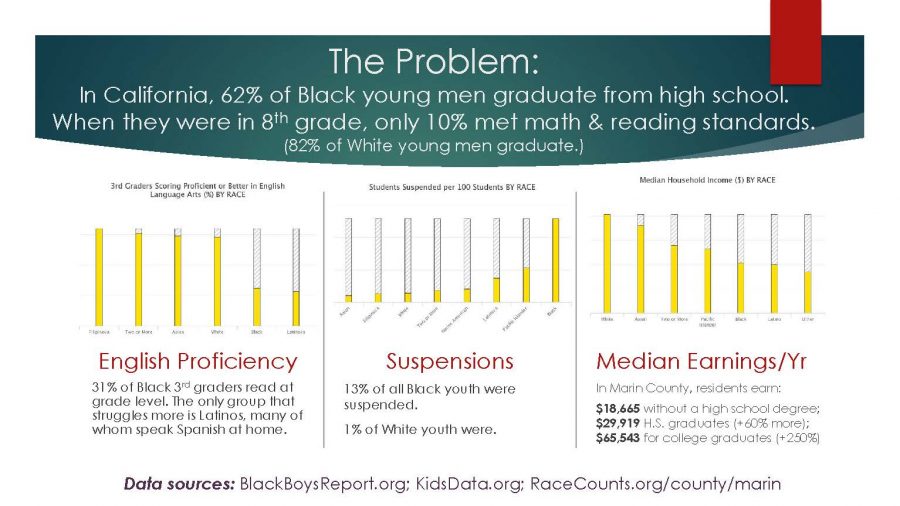

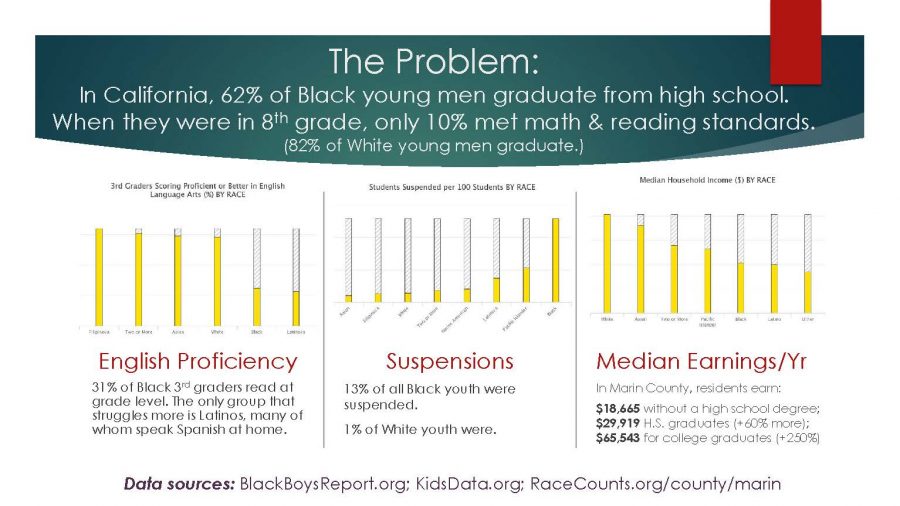

Marin City, which has a large African-American population, is poor compared to many of its neighbors in Marin County. Marin County has the highest levels of both prosperity and racial disparity in California, according to Race Counts, a 2017 report by Advancement Project California. Residents of Marin City earn just 38 percent what other Marin county residents do. Throughout the US, African Americans have been shown to have poor health outcomes, compared to their non-Hispanic white peers, and Marin City’s black population is no different. Research shows that residents in the nearby town of Ross, which is 89.5 percent white, live on average 11 years longer than Marin City residents.

The Marin County Health and Wellness Clinic (MCHWC) was launched with a simple but ambitious goal: to create health equity for African Americans. At its clinics in Marin City, San Rafael, and Bay View/Hunters Point, MCHWC provides a range of health services for people of all ages.

As part of its mission to improve the health of the local community, MCHWC established two youth empowerment programs: “The Defenders,” for boys, and “Girl Power,” for girls. The programs provide leadership and skills training, mentorship, and other support for Marin City youth.

As MCHWC staff provided health services and worked with young people through its youth programs, they began to recognize a disturbing pattern: many Marin City young people floundered once they got to high school. Marin City has one of the lowest education rates in the entire county, and the percentage of students who receive a high school degree has been decreasing in recent years.

Some statistics cited by MCHWC:

- 61 percent of Marin City residents age 25-34 have a high school degree or higher, compared to 85 percent of Marin County residents in the same age group.

- 53 percent of Marin City residents with less than a high school degree live in poverty, compared to 3 percent of those with a bachelor’s degree.

Part of the problem is that Marin County students often aren’t prepared for high school. Not only have many experienced adverse childhood experiences, including poverty, racism, and other forms of trauma that can affect learning, they also have few role models for success — in school or out. Students also go off to high school lacking the academic skills they need to succeed. Local Marin City schools are underfunded and resourced. Marin City’s K-8 school, where 78 percent of the students are African American, for example, had no full-time math or science teacher from 2012 to 2017. In the fall of 2017, school started three weeks late because of principal turnover and a lack of teachers.

When Marin City students start ninth grade at Tamalpais High School in neighboring Mill Valley, they typically aren’t as academically proficient as the other students who attend well-funded schools in Mill Valley and other wealthy towns. According to MCHWC’s Zared Lloyd, project lead and head teacher,”The education system is failing Marin City kids. We’d see it happen over and over. The kids are excited in freshman year; it’s a bigger campus and they’d enjoy it for a little while. But then the pressure begins to sink in: ‘I’m not doing too well.’ The kids tell us, ‘It feels like a set up. High school isn’t for us.’ Some start acting out, others fail or learn nothing and get passed onto the next grade, still unprepared. Many of them dropout, and then what are their options? They aren’t prepared for life, beyond a minimum wage job, or no job at all. It really is a school-to-prison pipeline.”

For Lloyd and others at MCHWC, it was clear that this lack of educational attainment was a threat to the long term health of the Marin City community. The solution also seemed obvious, if daunting: MCHWC needed to open its own high school for students the education system was leaving behind.

The Marin City High School Academy of Health and Wellness

Building a high school from the ground up is no easy task, and MCHWC staff didn’t underestimate the challenges they faced. But it was a plan they’d been considering for a long time, so when they had the opportunity to obtain seed funding and technical support from iLab, MCHWC staff were eager to try. In fact, even before they obtained funding, in the fall of 2017, they opened the school with volunteer teachers. In January 2018, they secured funding to launch a pilot, and the Marin City High School Academy of Health and Wellness was born.

The pilot started small, with just four students who were already affiliated with MCHWC through its youth empowerment programs. All were high school dropouts, and all had experienced various types of trauma: poverty, addiction (including exposure to drugs before birth), abuse, and homelessness.

iLab seed funding was used for the head teacher’s salary and expenses, which included planning, curriculum development, and teaching time. This funding also supported field trips and other types of experiential learning. CCI staffer, Jennifer Wright, worked as a coach with MCHWC. “Jenny was a terrific sounding board and thought partner,”says Zared Lloyd. “She helped connect us to resources and best-practices, giving feedback when solicited. She was also a champion for the organization and the project.” (Jenny talks about her experience here.) CCI innovation expert Seth Emont helped MCHWC staff design metrics to measure success.

Lloyd consulted other educational institutions to inform the school curriculum, with the goal of making it relevant to Marin City students. He carefully selected staff who supported the mission of the school, and were able to work with its student population. The goal was to incorporate both experiential and non-traditional learning, and to address the diverse needs of every student.

The long-term goals of the high school include:

- Increase chances of Marin City youth completing high school.

- Study STEM and African-American leadership, history, and cultural influence.

- Set a foundation for college.

- Decrease the likelihood of incarceration.

- Increase earning potential.