Seven teams spent the past year testing and clarifying the role that health care safety net organizations can play in addressing the social determinants of health through our Roles Outside Of Traditional Systems (ROOTS) program.

During the final in-person gathering, our teams shared the following advice for tackling upstream challenges, whether you’re just starting out or expanding this work:

1. Take baby steps.

This work can begin to seem very large, and move very fast. That’s why it’s important to start small and slow.

Create an environment to experiment with screening for social needs, linking patients with resources, and building interventions. It’s important to understand if the changes work well for staff and patients before spreading it clinic-wide.

It’s not about the number of patients that you screen, but your ability to respond to their needs. Remember: EVERY patient that you serve and connect is a success.

2. Win buy-in at every level of your organization.

It’s so important to include everyone — nurses, providers, community health workers, executives, etc. — in this process. Their engagement and training is a prerequisite for success. In fact, frontline staff are often the best leaders and champions of this work.

When strong leadership support and organizational buy-in exists, the main challenge becomes ”the how.” Figuring out how to best screen, track referrals, and integrate data becomes more important than making a case for doing the work. Key “how” questions include:

- How to screen? What are the best tools? How to ask these questions in ways that don’t stigmatize patients?

- How to integrate screening data into the EHR?

- What to do to help patients with non-medical needs? What assistance actually helps?

- How to identify effective partners? How to build effective partnerships?

- How to track referrals to outside organizations?

- How to measure success?

- How to motivate teams to do things differently and to add new work to already stretched workflows?

3. There’s value in screening.

Staff may feel uncomfortable asking patients about their social needs. However, using a screening tool or integrating questions into regular visits can be valuable to better understanding the overall needs of a patient. Some clinics are using PRAPARE, some are using other validated or homegrown tools. Others are combing tools and approaches.

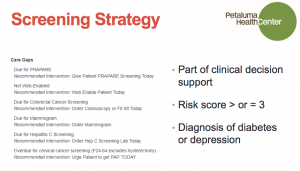

In 16 months, Petaluma Health Center went from screening 400 patients to 3,500 patients — 15 percent of its adult population. The key was embedding PRAPARE in its clinical decision support. Petaluma discovered that its original goal of screening its entire patient population once a year was too ambitious. So, using a data analytics tool, the staff honed in on specific populations by looking at care gaps. Any patient with a risk score of 3 or greater was screened with PRAPARE. In addition, any patient diagnosed with diabetes or depression was also screened.

4. And there’s also value in focusing on patient stories.

During site visits in Hawaii, our teams were introduced to the island concept of “talk-story.” We learned to hear patient stories and build connections through community health workers, navigators, and community leaders. Even without formal data, these roles know what patients really need. While protocols, like screening processes and tools, are important, so is coming together to eat food and cultivate relationships.

Take the practice of understanding people’s personal narratives very seriously. Listen, listen, listen.

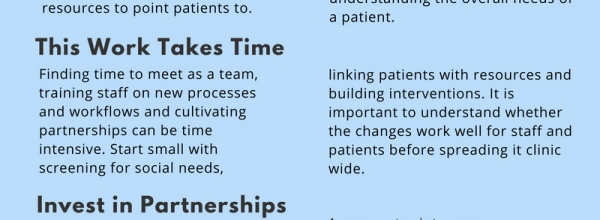

5. Hear out your patients — their lived experience can fill in gaps in data.

Public health data and community surveys are helpful. But the real local experts are sitting in your clinic.

Ask your patients: Other than medical care, what do you need to be more healthy? Or what is preventing you from living a healthier life?

For its project, LifeLong Medical Care worked on food insecurity in East Oakland. By engaging patients, it soon realized that connecting its patients with food banks only addressed part of the problem. Staff uncovered that some patients struggled with transportation to even get to food banks. Others didn’t have the physical strength to carry grocery bags up the stairs to their apartments. So LifeLong began delivering boxes of fresh produce to patient homes to help address barriers identified by their patients.

6. Technology isn’t the be-all, end-all.

Northeast Valley Health Corporation trained its care teams how to use Otech tablets to screen for food insecurity. While these tablets were great for improving efficiency, personal connection was truly the key to progress. If they had a do-over, NEVHC said it would have prepared staff in “empathic inquiry” before introducing the tablets. Because they had never asked social needs questions to adolescents, it would have been useful to first teach the staff techniques for listening to underlying feelings, needs, and values.

7. Forge partnerships within your organization — not just on the outside.

Identify what resources, knowledge and connections already exist in your organization before forging new partnerships. As you enter into new partnerships, it is essential to build trust by meeting in-person and clearly understand each other’s goals and intentions.

For its ROOTS project, LAC + USC Medical Center set out to address its primary care patients’ food insecurity. While investigating various resources, it discovered that the hospital already employed a staffer from the Los Angeles Department of Public Social Services. The money had already been allocated, but she couldn’t find the right patients to enroll in CalFresh. By partnering with primary care, that social services staffer was able to quadruple the number of people she served!

8. “Date” your potential partners.

You need time to court potential partners. Get to know where they’re at, what they’re looking for, and how it aligns with what your own needs.

You don’t know until you ask: Petaluma Health Center’s project focused on connecting unemployed adults with job opportunities. At first, it struggled with finding its patients transportation to job fairs and trainings. But then it asked Sonoma County Job Link for help and, as it turns out, the organization already had funding for transportation!

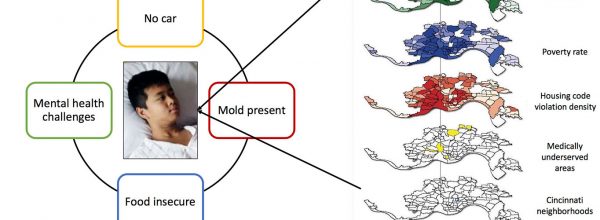

9. Vet your referrals and partners.

Before you make a referral, be sure to develop some personal knowledge about that intervention. Build relationships to facilitate “warm handoffs” between the clinic and the community.

At the same time, realize that not all patients require the same level of assistance. The intensity of the assistance should be tailored to match the complexity of their needs.

During ROOTS, Asian Health Services focused on developing infrastructure and community linkages to address housing and food insecurity. It realized few of its patients were using local food banks. So it sent interns to find the closest food banks to Chinatown with staffers who speak multiple languages. This made all the difference. Asian Health Services stressed that screenings must go hand-in-hand with culturally responsive, accessible, and consistent interventions.

It’s hard to know what your patients will experience if you’ve never seen it yourself, says Petaluma Health Services.

10. Close the loop.

There are four strategies to making sure referrals aren’t lost in the shuffle:

- Improve the referral process — Consider making an “active referral” that directly connects to the community-based organization. This removes the burden off the patient to complete the referral themselves.

- Develop partnerships — Follow up with the community partner instead of the patient. This will help formalize relationships with your partner and develop communication channels to share referral and completion information.

- Technology solutions — Resource and referral databases exist to provide sourcing, referral and follow-up via a technology platform.

- Patient follow-up — Flag the patients that screen positive for a social need. Consult your list and touch base with these patients about their referral when they come back for a follow-up appointment.

And, most importantly, tell your patients the various ways to get in touch, says St. John’s Well Child and Family Center. If you don’t have the right resource for them, stress that you’re working on a solution — “You may not have housing tonight, but we may have something for you tomorrow.”

11. Data exchanges with partners are complex, but it can be done!

We learned that more collaboration opportunities generated more questions about data privacy and security.

During ROOTS, West County Health Centers partnered with the Guerneville School District to understand the factors that influence absenteeism and create a solution together. To do so, the partners would jointly evaluate their data on patients and students.

But, in adopting new analytical tools and datasets, West County quickly discovered that many ethical and legal boundaries had yet to be defined. For instance, who was allowed to see the data? How do you share it in a safe and secure way? Did you need parent permission? This was uncharted territory.

The solution was a legal agreement to ingest pupil-level data and join it with West County’s own patient identified data. It limited who had access to pull student data and how it would be used.

12. Paying for this work is complex.

There are many models to finance upstream activities. Community health center leaders are scrambling to leverage traditional federal sources, alternative Medicaid sources, and Medicaid Shared Savings programs. Many are of pulling together a hodgepodge of volunteers and grants to fund positions and programs.

West County Health Centers CEO Mary Szecsey recommends working with your managed care plans in partnership with your consortia.

But there isn’t one stable, sustainable way to support this work in the months and years to come.

13. Be adaptable.

You’re not going to get it right the first time. This work requires iterating ideas, workflows, and processes, as you gather more and more feedback from patients and clinic staff.

14. Persistence is fertile!

Take your time — this work can’t be rushed.

Finding time to meet as a team, training staff on new processes and workflows, and cultivating partnerships can eat up a lot of your schedule.

Our ROOTS teams shared this lesson with us over and over again: Organizations need protected time to build leadership and staff buy-in, gather patient information, and develop partnerships with external community organizations. But keep at it and you’ll be rewarded.

And so, after all this, what’s the right role for clinics to play?

And after a year of testing and learning, what do we (and the clinics in our program) think the role of the clinics in assessing and addressing social needs should be? The answer isn’t simple. While most clinics in our program focused on the role of screening and referring patients, we’ve learned through ROOTS and other CCI programs that there are additional roles to play, like:

- Community convener

- Data steward

- Creator of economic opportunity

- Operator of a social enterprise and job creator

- Advocate

The appropriate role might actually depend on organizational philosophies, leadership priorities, clinic history, other available community services, location, and size.

Stay tuned for updates, and the evolution of our thinking, as we plan to release the official evaluation results, case studies, and lessons learned in partnership with our evaluation team at SIREN in early January 2019!

Find this useful or interesting? We’re constantly sharing stuff like this. Sign up to receive our newsletter to stay in the loop.