A wrinkle in the safety net

For more than 150 years, Los Angeles County has offered quality medical care to residents whether they were able to pay or not. Built in 1860, the Los Angeles Department of Health Services provides health services to patients in what is now known as the Los Angeles safety net.

Today the department is a municipal county health system located in the city of Los Angeles, a sprawling metropolis of four million people.

The nation’s second largest municipal health system, the LA County DHS cares for more than 600,000 patients annually, 80 percent of whom receive public insurance through Medi-Cal. The organization is a leader in trauma and burn care as well as chronic disease management. No one is turned away: Its doctors, nurses and other employees work around the clock to take care of patients who are low-income, uninsured, homeless, speak little or no English, and/or have disabilities or substance abuse problems.

But the long queues at the Medical Record lines were unsettling — not exactly a hole in the safety net, but a wrinkle of sorts. How did patients feel about the long waits? Which kinds of medical records were they looking for? And importantly, what would be a better way for them to access their records? Dr. Abhat and the department decided to do a survey to find out.

“A big undertaking”

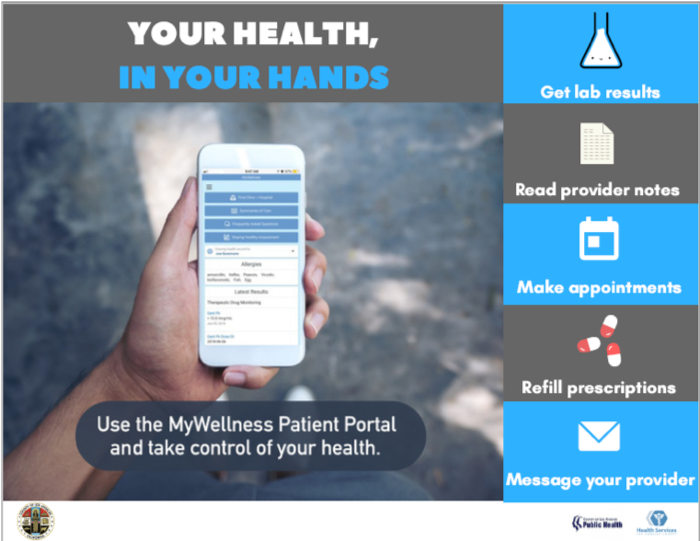

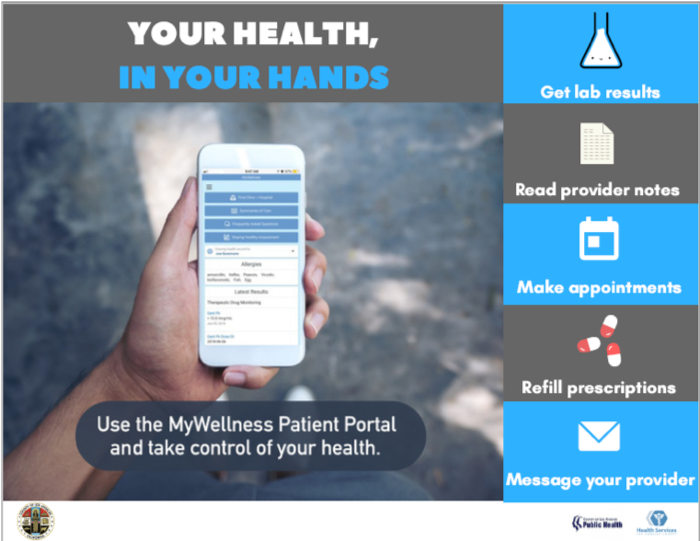

To find out what was doing on, the department did surveys of patients at all sites who were waiting in Medical Records lines from January through March of 2017. The goals? To better understand their internet accessibility, their knowledge about the LA County DHS MyWellness patient portal, and last but not least, to find out why they were standing in the Medical Records line.

“It was a big undertaking: this was very different from gathering data at one facility,” says Dr. Abhat, who serves as Director of Digital Patient Engagement for the health care network. “We have four hospitals and 18 clinics, and trying to get data from all those sites is really challenging.”

Most of the staff members assigned to the surveys were nurses, clerical workers and administrative staffers. Some carried tablets to fill out the survey online. Others printed out the surveys for patient who were more comfortable with paper, then scanned and faxed them to headquarters when they were collated.

The survey results were eye-opening. Patients reported they were planning to get copies of (in order of importance) 1) laboratory results; 2) medical provider notes; and 3) radiology reports. Unfortunately, the experience was a drain on both their time and their wallet:

- Patients reported losing “a significant chunk of their day” driving to the clinic or hospital, hunting for a parking place in areas where that was a major headache, spending up to an hour in line, and driving back home.

- The cost was exorbitant, including, in some cases, both lost wages and up to $250 in printing costs for the medical records.

- Many found it difficult to take time off work or away from the family to get their records, especially if they were primary caregivers.

Despite these challenges, the team learned that patients were eager to engage in their health care “and wanted to have the data right at their fingertips,” said Dr. Abhat. Patients wanted their data and medical records available online – especially so they could avoid the Medical Records line — and they were enthusiastic about an online patient portal.

The team was gratified by the survey results. “It was good data, very foundational,” said Dr. Abhat. “We realized this was a tremendous opportunity to improve access to health information for our patients.”

A game-changing plan for online access

Dr. Abhat proposed an online solution to the leadership of the LA County Department of Health Services: rolling out medical records through OpenNotes– an international movement that promotes transparency in medicine.

Credit: OpenNotes

Dr. Abhat was one of the very first doctors to use OpenNotes because she was part of the original pilot study on it when she was a provider at Harborview Medical Center at the University of Washington in Seattle.

“I was very open to the idea of sharing my own medical notes,” she recalled. “You were lucky if you got a patient to read your notes. It was great to get patients to engage.”

In Los Angeles County, the department was already part of the way toward transparency. During the recession, the LA County DHS had received some funds from the federal Meaningful Use to help with the costly work of implementing a new electronic health record (EHR) online and to build the MyWellness patient portal. “We had basically used the portal to release lab reports online, and I knew we could do so much more,” Dr. Abhat recalled. In March 2017 the department made radiology records available online, and by April, patients were able to self-enroll in the department’s MyWellness patient portal.

To get data on patients’ views of the portal, in May the department commissioned a series of research focus groups in English and Spanish with Dr. Alejandra Casillas, a researcher in the division of General Internal Medicine at UCLA. That same month, the DHS Executive Clinical Operations team had approved the launch of OpenNotes across all hospitals and clinics. To discuss OpenNotes and answer questions about it, the launch team set aside June through August 2017 to meet with providers and health system personnel.

First, they spent time explaining what OpenNotes was. It may sound like an app or software “or someplace in the sky where medical records are stored,” as one staff member said, but it’s not: It’s a movement to make healthcare more transparent “by urging doctors, nurses, therapists and others to invite patients to read the notes they write to describe a visit.” In other words, Open Notes. As one radiology journal recently pointed out, studies have linked this practice to “improvements in patients’ understanding of their health, promotion of shared decision making and patient-provider communication, and, ultimately, improvements in patient outcomes.”

Some doctors have welcomed OpenNotes with open arms. “Transparency engages and empowers people,” says Dr. Lauren Bruckner, the medical director of patient engagement and attending physician in pediatric oncology at the University of Rochester Medical Center. “Evidence has shown that more engaged patients have better clinical outcomes and are more satisfied with their healthcare experience. In this context, OpenNotes should really be a no-brainer. Can you think of another example in medicine where there has been so many positive results coupled with overwhelming patient approval and support, very little to no extra work needed by clinicians, and it’s FREE!?

“The major barrier is culture change — despite ample experience and evidence to the contrary, clinicians fear that sharing doctors’ notes may harm their patients, create extra work for them, and/or require them to change the way they write their notes. The challenge is convincing providers to just try it.”

(Read our Q&A with Dr. Bruckner)

Indeed, doctors tend to resist the idea, at least at first. In the original evaluation and demonstration study on OpenNotes, conducted at health systems in Washington, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts in 2010, researchers found physicians feared that turning over their medical notes to patients would result in an additional burden on providers.

“They thought patients were going to call us all the time because they didn’t understand something written in a note,” said Dr. Abhat. “But the study found that there really wasn’t much change – and that there was almost zero change in the work done by the doctor. Some doctors spent a little more time writing up their notes, but there was not significantly more time spent on messaging.” She and other leaders were excited to roll out the idea of OpenNotes to the network.

Getting Buy-In

But like the doctors in the original study of OpenNotes, some physicians at the LA County DHS were alarmed by the idea of sharing their notes with patients.

“We got somewhat of a mixed reaction,” Dr. Abhat acknowledged. “It is hard to get a sense of what providers are feeling when you have 18 clinics all over Los Angeles.” Some doctors felt it would help and said things like, ‘Why haven’t you done that yet?’ Others said, ‘No, that’s crazy, what if patients don’t like my diagnosis?!’ And some said, ‘Well, it’s going to happen anyway; let’s move on.’ We are a very, very large system, so we pulled in CMOs or CMIOs and asked them to communicate the message to their staff.”

Whenever health systems decide to implement OpenNotes, staff at the non-profit make themselves available as needed — to talk with clinical staff, answer questions about data, or partner on a study. In the LA County DHS rollout, providers at one clinic had what Dr. Abhat called “a pretty negative reaction.” To deal with their concerns, she presented at Grand Rounds at the facility with Liz Salmi, a patient and now a senior strategist at OpenNotes. Instead of going straight into the data, Salmi said, she decided to first tell her story as a patient.

“I began by telling them how one day, out of the blue, I had a grand mal seizure and was taken to the ER and found out I had malignant brain cancer,” said Salmi. And then the room got very quiet.” She remembers seeing some medical workers in the audience smile at her encouragingly, willing her keep talking, to share her story.

Salmi explained that when her health insurance changed, she went to get a copy of her medical records at 15 cents a page “and it was 4,800 pages long!” She finally managed to get two computer discs with all her medical records, including doctors’ notes. “I just started reading, and it was really amazing to go back and relive my life eight years from diagnosis,” she said. “There was not a single thing there I could not figure out in context, and the doctors’ notes answered every unanswered question I had had about the cancer, this thing that was affecting every single thing in my life…I just wish I’d seen them sooner.”

Salmi went on to talk about the dozens of studies about OpenNotes, including a considerable body of research that showed no increase in physician workload but a significant increase in patient trust and satisfaction. “Liz is an incredible human being, very talented and a very powerful speaker,” said Dr. Abhat. “It changed a lot of hearts and minds in the room, including a lot of people who initially wanted to shut down the launch of OpenNotes.”

After many rounds of educational sessions and teleconferencing, the launch team felt that it had satisfied everyone’s concerns. They planned to launch OpenNotes in August 2017, but there was a jarring surprise in store.

Primary care physicians at a particular clinic who had not felt comfortable voicing their fears suddenly came forward. The launch was delayed for several months, she said, while the team met with them and union representatives to discuss their concerns “and strike a middle ground so we could move forward.”

“It was a necessary part of the process; we really learned a lot,” Dr. Abhat said about slowing down the implementation to allay concerns. Among other things, the launch team agreed to hold back on releasing mental health notes. Members continued to work closely with providers until the first phase of the OpenNotes launch in January 2018.

Three months later, after evaluating the spread and impact of the first phase of the launch, the team rolled out OpenNotes in primary care.

Results

The roll-out of the updated patient portal and OpenNotes was well-received. The extra work some doctors had feared? It didn’t materialize. Out of 150,000 estimated encounters with patients, there was only one negative exchange — a complaint from a patient who didn’t agree with his diagnosis. “Everyone thinks the sky is going to fall down and then nothing happens,” Dr. Abhat said. “I haven’t heard from those concerned providers – I think [the rollout] just happened and they stopped thinking about it.”

Out of the 600,000 unique patients seen in the health system, 300,000 were assigned to primary care providers through MediCal and Medicare. This was the target population for the MyWellness patient portal. From the early data the team was amassing, the metrics were impressive, even astonishing:

- Active patients on the MyWellness patient portal increased by 100% over the year, from 12,500 a month in January 2018 to 24,000 a month in December of that year.

- Overall enrollment in the patient portal increased from 6% to 14% in the the target population, with the highest-performing primary care clinics seeing 20% enrollment and specialty clinics seeing 30 to 35% enrollment among women and teens.

- 55,000 patients are now enrolled on the MyWellness portal.

- OpenNotes page views increased from 2,000 pages per month (January 2018) to 9,300 page views a month (December 2018).

- In 2018, the LA County DHS saw 83,000 views of OpenNotes.

Dr. Manuel Campa

There were still lines for Medical Records, but they were smaller. Meanwhile, physicians reporting hearing moving testimonies from their clientele about the new technology.

Among them was one from a homeless patient in primary care, who was devoted to the patient portal, according to Dr. Manuel Campa. The man, who had multiple chronic conditions, had no access to a phone and lived in his car. “The only way he has been able to access his care team when he is outside the clinic is via the MyWellness message feature,” said Campa, who works at an LA County primary care clinic and USC. His patient went to the local library to use the portal and communicate concerns about his physical or mental health. He also used it when he needed to write to the specialty clinic.

“He gives shout-outs to our clinic team,” said Campa. “He says the MyWellness patient portal ‘helps him feel connected to the clinic,’ and that he can express himself more easily through the message feature than in person.”

A clerk at another facility recounts the story of a primary care patient who went to a lab for results, only to be directed (wrongly, as it turned out) to the clinic.

“He came to our clinic angry and frustrated,” said Ivana Cervantes, who works at Adult Primary Care West LAC and USC. The man was told the clinic couldn’t give him the records, but that the staff would help him enroll in the MyWellness patient portal. He enrolled, viewed his lab results, and came back to the clinic three weeks later — this time in a very different mood. Cervantes recounts that he told the staff “how grateful he was for being able to see his labs without have to go to medical records and pay for them.”

Credit: OpenNotes

From her own perspective, Dr. Abhat sees a difference in her practice. “I now tell my patients, go read my notes after our visit today on the MyWellness patient portal,” she said, noting that she includes links for them to look at their diabetes and weight management like learningaboutdiabetes.org or MyFitnessPal. As she tells her patients, “That way you don’t have to remember apps and websites or worry about losing the printed papers after their visit…[I tell them], ‘the next time you come to see me, give me feedback on your experience and reading the notes.’”

The response from patients has been overwhelmingly positive. In fact, one patient, Jeff Graner, a patient and peer mentor in a stroke rehab facility, was inspired to do his own survey about the MyWellness portal and OpenNotes.

In December 2018, Dr. Abhat presented the outcomes to the DHS Executive Clinical Operations Committee and the California OpenNotes Consortium.

“For a giant county health system with such a diverse group of patients to adopt OpenNotes is a very big deal,” says Salmi. “Other health systems can learn a lot from them.” Sixty hospitals, clinics, or associations in California are looking into OpenNotes, in fact, and 26 are already using it, including UCLA, UC San Diego, and Stanford.