The Problem

Though part of California’s Wine Country, the town has the country’s third largest population of chronically homeless in a suburban area. Credit: Acp 2011 [CC BY-SA 4.0]

Homelessness in Sonoma County is a growing issue throughout Sonoma County – and it’s on the rise. The county counted 2,657 homeless adults living outdoors or in shelters in 2018, a figure that was 6 percent higher than in 2017, according to the Santa Rosa Press Democrat. The newspaper called it “one of the county’s most stubborn public health problems…one that is getting worse after years of improvement.”

In fact, Sonoma County appeared in a recent federal report to Congress as having one of the country’s largest homeless populations in a largely suburban area, including one of the highest number of unaccompanied youth, and its number of chronically homeless – that is, people who have been homeless for more than a year – has grown by 25 percent since 2017, making it the third highest in the nation. Housing advocates blame soaring rents, low wages and an overwhelming shortage of permanent housing for homeless people, forcing them into a revolving door of temporary shelters.

WCHC has offered Healthcare for the Homeless services since 2016. The program was designed to remove barriers to health care for the homeless — especially since clinicians observed that homelessness results in higher rates of mental and physical health problems.

The health centers offer a full plate of interventions: transportation assistance (Check out our case study on WCHC’s rural transportation solution), behavioral health and psychiatric care, substance abuse counseling, case management, primary care, dental care and outreach. Research on the social determinants of health (SDOH) has proven that there are many factors other than access to quality healthcare that influence health outcomes, and clinic workers know well that homelessness can lead to or exacerbate chronic health problems. As Figoni explains, “We use a ‘no wrong door’ approach to the local health care system,” partnering with other agencies to provide life-stabilizing services and to integrate health services into shelters and government housing.

“Often times, even when housing becomes available, people experiencing homelessness lack the resources and social supports to successfully navigate the move to housing,” Figoni explains. “For many people who have experienced long-term homelessness, clinical support — including behavioral health — are essential to long term success in housing. We work closely with housing providers to integrate our care team into their existing housing case management services. While we do not operate housing programs, we do recognize the impact of housing on healthcare and seek to not only improve people’s access to affordable housing, but to support their long-term success so they never return to homelessness.”

But to be as effective as they wanted to be, team members needed more and better data. The transient nature of the homeless made it difficult to coordinate care, do strategic planning and respond in a timely way to patients. Simply finding out where to see a patient was inordinately difficult: The staff lacked a mechanism to identify, document and track the location of the patient for care delivery. This problem was compounded in times of crisis, when timely access to care and coordination is crucial.

As Figoni and Woodbyrne explained in a recent presentation, “While many programs have been created to help those affected by homelessness, getting the right resources to people when and where they need them is still an obstacle an organization like ours faces. Gathering real-time data to help identify these needs is critical.”

The Solution

The team chose to explore geo-mapping. If you haven’t heard of it, geo-mapping is a tool that helps teams collect strong data in the field and turn it into a visual map of where they collected it.

As Figoni and Woodbyrne explain, this technology helps communities understands the disparities and gaps that occur among the homeless “by visually uncovering patterns and trends.”

The basic steps, Figoni has explained, are to:

- Create your survey.

- Meet patients out in the field.

- Collect survey data while doing outreach.

- Uncover patterns by mapping the survey data.

- Act on the data.

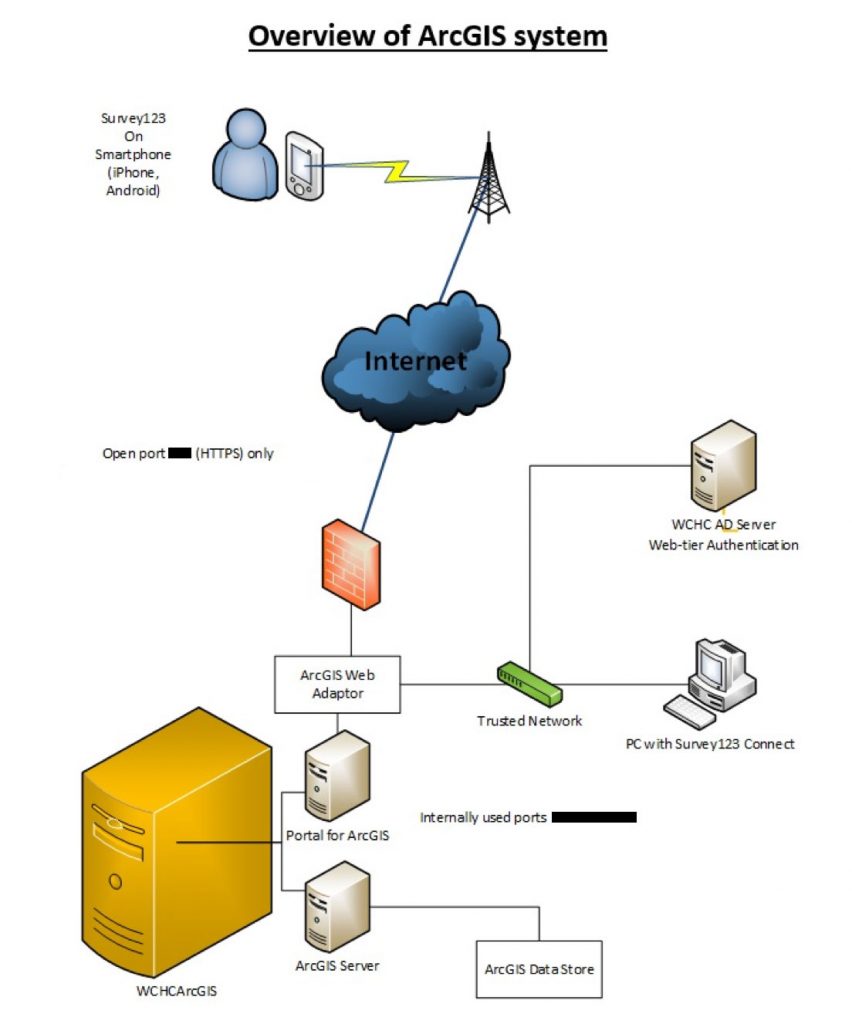

The team chose a geo-mapping tool called Survey123 by ArcGIS, a tool that uses a Geographic Information System (GIS) to integrate geographic location elements into a survey to better understand a given population or question. WCHC’s Innovations Department researched how organizations across the United States have implemented geo-mapping into their practice and decided to use it to better serve their homeless patients.

“We hoped this tool would allow our Healthcare for the Homeless team to understand and respond to disparities that occur among those who are affected by homelessness,” Figoni noted. Specifically, WCHC wanted to be able to securely manage data, including protected health information (PHI), in a way that incorporates geographic locations and map layers to create a more holistic approach relevant to patient care. By putting this into the hands of staff who provide direct patient care, Figoni continued, this team planned to produce a map to help them:

- Track specific individuals as they migrated during seasonal changes or changes in status.

- Local individuals for medication drop-off.

- Hot spot real-time resources for the homeless population.

- Identify and locate individuals in emergency disaster situations.

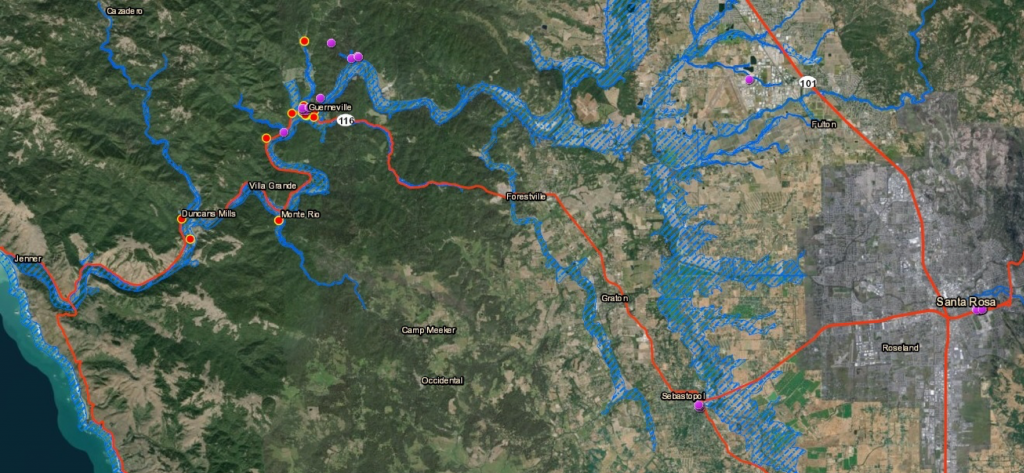

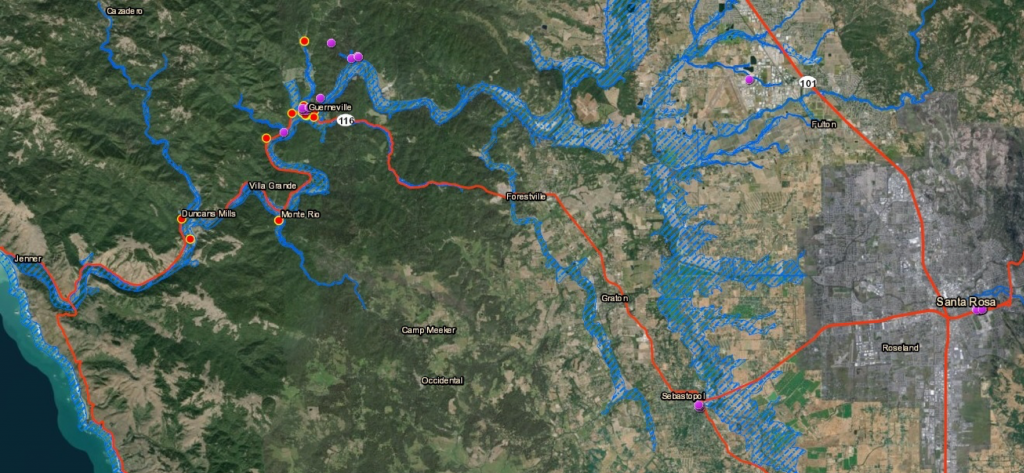

The latter would prove invaluable during the Guerneville flood of spring 2019, when the ArcGIS map allowed clinic members to locate their HCH patients from the river encampments (marked on an ArcGIS map below).

Pre- and -post flood evaluation: Geolocated red dots represent patients that were marked prior to the flood. Purple dots represent patients that were marked after the flood. When you click a dot on the map you can see the patients survey response associated with it.

Bringing the Project to Life

In September 2018 WCHC developed a timeline, project team and metrics for the geo-mapping project. This timeline was broken down into three phases, (1) technology fluency and implementation (2) developing and testing a meaningful survey, and (3) putting practice into action.

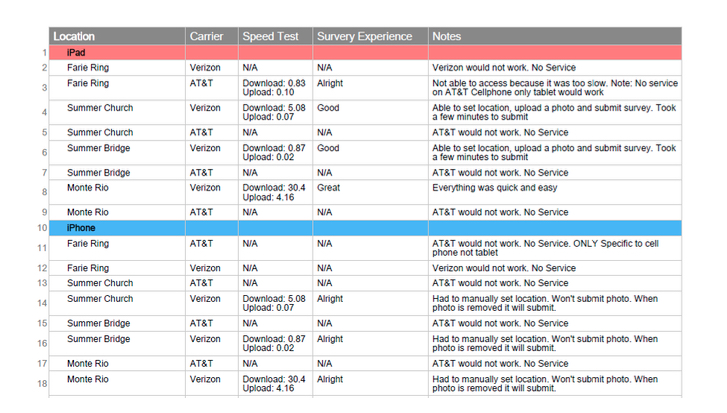

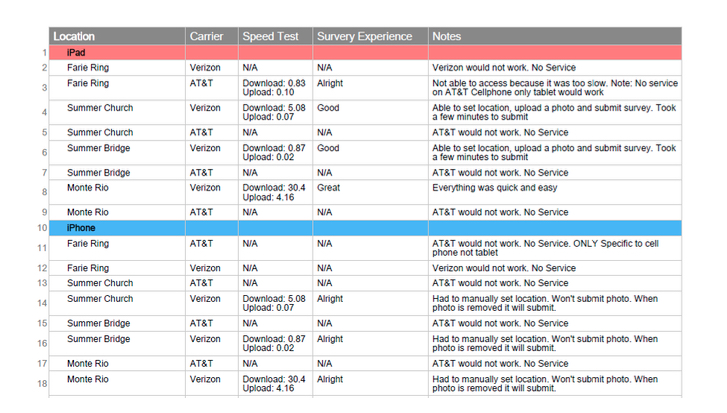

1. Developing technological fluency

During this phase, the WCHC team explored ways to test technology connectivity in the rural areas of the Russian River. By building this time into its project plan, team members were able to successfully test various technology devices (iPhone, Tablet & iPad), carriers (AT&T and Verizon) and conduct LTE speed tests at various encampments. These findings were critical to the integrity of the project. Because WCHC tested technology components, it was able to determine that a Verizon iPad would be the most suitable for submitting surveys out in the field because AT&T dropped too many calls (see below).

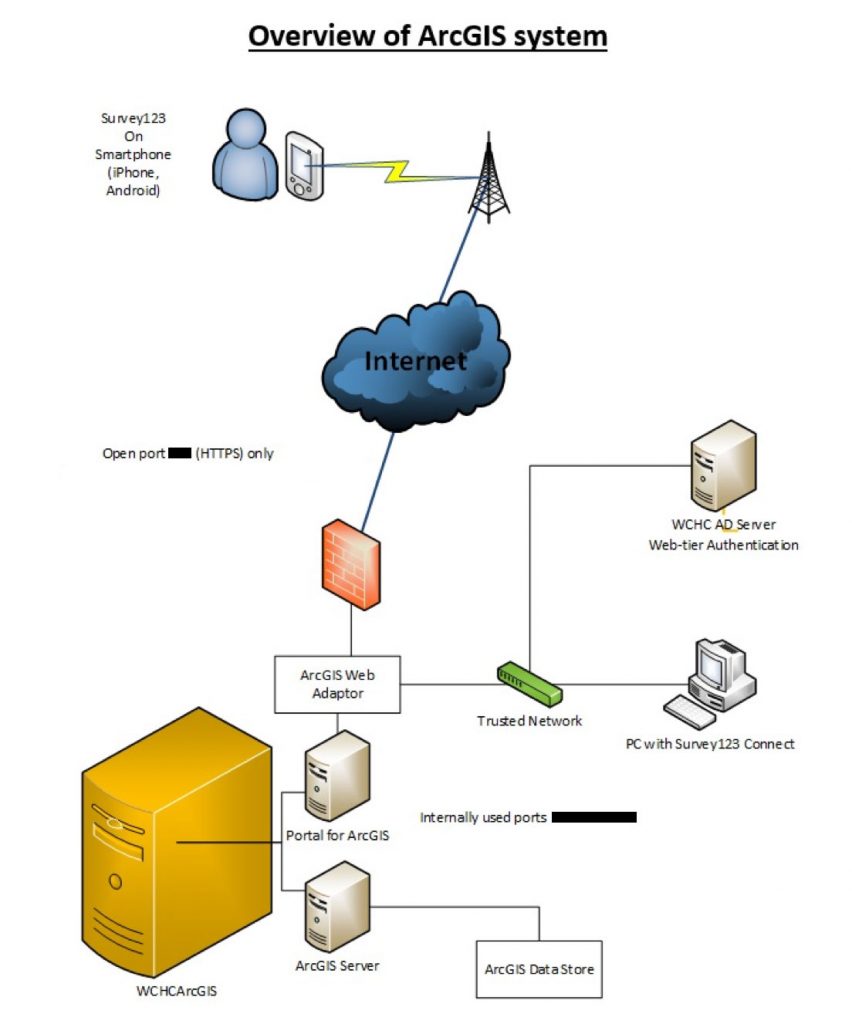

At the same time, the team worked with its IT Vendor, KLH Consulting, to start the process of working with KLH engineers to use an ArcGIS internal server to store PHI surveys. The project team decided in its first project team meeting that making surveys meaningful meant associating protected health information (PHI) with where staffers met the patient. “Because we knew early on that identifying a server and configuring it to meet our needs would take quite some time, we decided to move into the next stage of this project – testing a deidentified survey with our patients,” Figoni noted. The capability to upload and store PHI was completed in January 2019.

2. Creating and taking surveys

Administrators and outreach staff began planning their geo-mapping surveys, which could be created in a matter of minutes. The staff member simply logged into the Survey123 web or desktop app, opened “Create New Survey” from a drop-down menu, entered the name of the survey, and then clicked “create.” After doing that, the staff member would see a preview of the survey on the left-hand pane and a list of ‘usable questions” on the right-hand side. He or she then choses from a list of usable questions on the right-hand pane, then clicks “publish” so that the survey was available for use.

Field collection is a critical part of any Geographic Information System, and the Healthcare for the Homeless program was no exception. Smartphones and devices made it easier to for the WCHC staff to turn a field observation into a point on a map. Team members also used a human-centered design technique to brainstorm what would make the data relevant, objective and accurate. Because Survey123 runs on both desktop and mobile devices, staff members were able to collect data with their own hardware—their Verizon IPads. Team members decided to take half a day and do some preliminary testing at an encampment.

Those four hours were an eye-opener. “Not more than 20 minutes into our testing, we learned that we needed to create a script prior to connecting with our patients,” Figoni would write later. “When we approached this population and asked them if they were interested in taking this survey, we used words like “geo-mapping,” “pinpoint,” or “data collection.” These words instantly made our patients uncomfortable. We also learned that patients did not want to take the survey themselves and preferred that we ask them these questions. A patient told us that iPads, iPhones, and so on often get stolen among this population. Putting this technology into their hands felt scary to them because they did not want to be responsible for it getting stolen or lost. In addition, we also learned that our patients were open to talking about resources that they needed.”

After brainstorming and designing a survey about resources needed at given locations, the project team spent a month locating and asking the survey questions. They connected with 58 patients at various encampments throughout the lower Russian River. “We had amazing success this time around because we had a script and asked the questions ourselves,” Figoni recalled. But more surprises were in store.

Understanding Patients’ Needs

Staff members out in the field were able to upload the data immediately and those back in the office could immediately analyze those responses in real-time. To view the results of the survey, a staff member simply had to (1) log into the Survey123 app through the web or desktop (2) select the appropriate survey; and 3) view geopoint survey results in real-time.

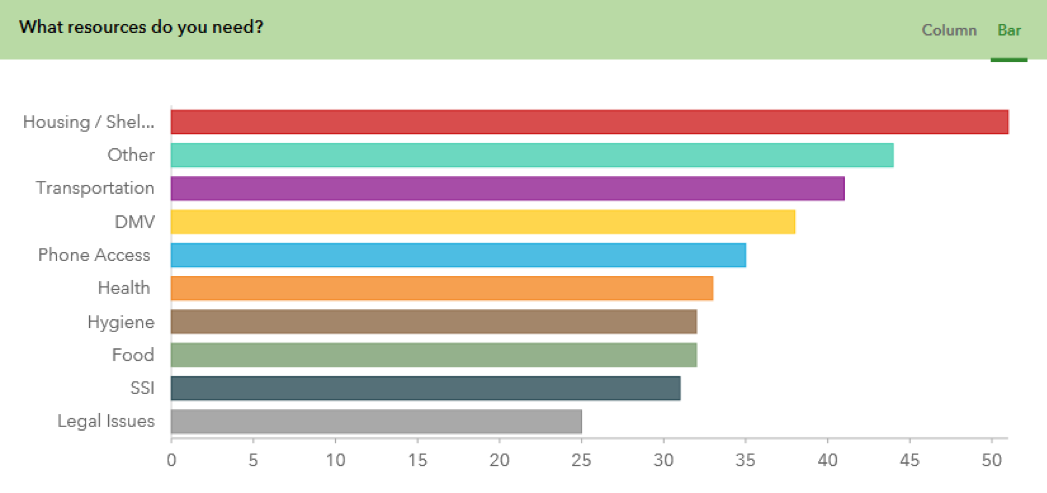

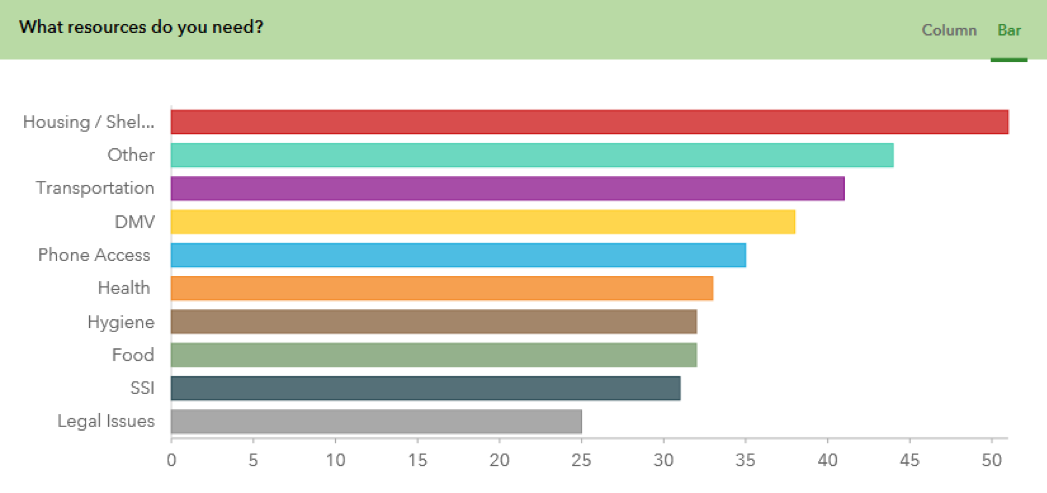

Below, a bar chart created by Survey123 in real time highlights the data patients current needed access to.

The survey results were striking. Not surprisingly, housing was the highest priority, with transportation, DMV issues, phone access, health and hygiene were high on the list, with food, SSI and legal issues a little lower. The second highest category, however, was a free text option in which patients could write in their own answers, and the geo-mapping tool supplied a word cloud that summarized those findings:

One of the most poignant findings was that bathrooms were at the top of the priorities the homeless patients listed for themselves. It turns out that Guerneville only has one public bathroom, which is only open 9am to 5pm on weekdays and is closed on the weekend. This, in turn, had had a negative impact on residents’ eating habits. “Some homeless patients said they only ate in the morning so they wouldn’t [have a bowel movement] after the bathroom was locked in the evening,” said Figoni. “It’s ironic because we live in an amazing, generous county where there is so much good food available to the homeless, and patients acknowledged that, but they were so worried about having to go when no bathroom was available that they limited themselves to one meal a day.”

Other needs residents brought up included jobs and employment, storage, refrigeration, showers, vet care, SNAP and safety. “Some said, ‘I need help with my health insurance. ‘I need dog food.’ ‘I just need a safe place to go during the day,’ said Figoni. Also, the survey suggested a longing for connection: Calls for better WiFi, reliable cell service, counseling, and “a safe place to talk about our life experiences.”

“Being able to look at the geolocated data we collected in real-time has been immensely helpful in figuring out what this highly vulnerable population needs,” said outreach worker Vanessa Woodbyrne. “It has been enlightening to build this rapport with our clients and get a better idea of what sort of resources are actually helpful for them. I noticed a lot of the time what I thought would be a necessity to our client’s lives was not actually something essential to their current situation.”

The survey (and all other surveys) have a GIS component that generates a latitudinal/longitudinal marker for the location of the individual completing the survey or can be added at a future date by dropping a pin on a location.

After collecting the survey results, team members could enhance the aggregated map layer with a vast number of publicly available map layers through the ArcGIS library interface. These could include more static layers, such as locations of bus stops/roadways or evolving layers such as current location of a flood/fire boundary.

3. Putting the application into practice

West County Health Center Healthcare for the Homeless staff and agency leadership are now brainstorming other applications of this technology for direct patient care along with strategic planning. Examples of projects include ongoing monitoring of medication drop-off locations; figuring out specific needs of a given areas to understand resource gaps; use in future disaster planning, disease outreach, and infectious disease planning; collaboration with key partners such as first responders and county mental health services; and giving patients access to a survey to upload their location and ask for direct service such as medication or direct patient care.

Some homeless patients told providers that they wanted to be able to notify their friends or family if they were ill, taken to the hospital or arrested; they wanted them to know where they were. The team is working on the second phase of a project involving PHI that will generate a message to friends or family through the tool, if the patient so chooses.

“I am convinced that the use of location-based technology has the potential to add insight into the context in which our patients live their lives and can transform the way in which we think about care delivery and evaluate its success,” said Dr. Jason Cunningham, chief medical officer of West County Health Centers.