“Equity cannot be a ‘project’. If it’s framed as a project, it is going to be very hard for it to be successful.” –Tosan Boyo, COO, Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital

When Tosan Boyo began working at San Francisco General, it was the spring of 2017. The Muslim ban had gone into effect. ICE deportation raids against migrants were soaring. At the hospital, Muslim staff were distraught because of the possibility they couldn’t visit their families. Additionally, there was concern Latino patients might not show up to their appointments or the Emergency Department for fear their information might wind up in the hands of different government agencies.

Tosan Boyo, COO of ZSF General Hospital

“A lot of our staff felt unsafe,” said Boyo. “A lot of our patients felt unsafe. The question was, what was San Francisco General going to do about it, especially since we strive to be the sanctuary within a sanctuary. What was our equity journey going to look like, and how could we make it central?”

Boyo had long had an interest in equity issues. Born in Nigeria and raised in New Jersey, he has backpacked across seven continents – an experience that he said shaped his view on how culture, policy and health affect vulnerable communities.

But race and equity also cut close to home. With a master’s degree in public health from Montclair, Boyo has worked as a healthcare manager and executive in New Jersey and cities across California. However, as a Black man, he was always aware that even a routine traffic stop by the police could go horribly wrong. During one Bay Area job that required a daily 70-mile roundtrip commute which began and ended in the dark, he kept his hospital ID pinned on his collar to avoid sudden moves in case he was stopped and asked by an officer for his ID. He remembers how his “compartmentalized worlds” shattered when Philandro Castile – a Black nutrition services supervisor in Minnesota wrongly suspected of a robbery – was stopped driving home and shot in the car by a police officer seven times at point blank range in front of his girlfriend and four-year-old daughter.

“The video of him dying hit me hard. I was unwise in watching it before my commute,” Boyo wrote later in a story for Health Evolution. “Unable to contain my grief, I pulled over on Bridge 92 and wept. It could’ve been me. That day at my hospital, I opened up our executive team meeting by reflecting on Philando’s death, what it meant to me and the impact health care leaders can have. Our operations revolve around healing, life and death. I believe we have a duty to advance equity.”

At San Francisco General, Boyo decided to start just as any scientist would: By examining the data. He looked at the hospitals’s number one quality metric, which was readmissions. “I wanted to understand what the number one driver was for readmissions,” he said. “It was heart failure. At this point in time, the organization was very close to hitting the readmissions target.” Since the hospital had no equity strategy then in place, Boyo volunteered to take the lead. He broke down the data by race to see how many patients were hitting the readmissions target. As he investigated the overall target success rate, what he found was unsettling.

The Telltale Heart

It turned out that Black and African American patients were being readmitted for heart failure at hugely disproportionate rates compared to whites. “I asked the executive team as the chief operating officer, ‘Are we going to truly say that we are being successful if not every population is hitting the readmissions target?’”

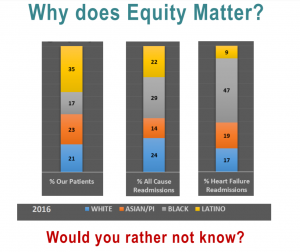

Slide from Tosan Boyo

In a recent Center for Care Innovations webinar on health equity, Boyo outlined his findings. He pointed to a slide breaking down the San Francisco General readmissions data by race. “Here, you can see that black and African American patients made up 47 percent of the patients who were readmitted due to heart failure, which was the number one readmissions driver for black or African Americans, and yet they only represented 17 percent of the entire patient population. So, my question to the organization was: ‘Why does equity matter? Are we okay with having this type of disparity?’”

The young COO immediately got pushback from some leaders and physicians at the hospital. “They were saying, ‘Hey, you know, if we’re going to make this a priority, what are we going to do when we find out that there’s a disparity?’ Or, ‘It’s going to be a lot of work to try and do the drilling with the data.’ And my pushback was, ‘Would you rather not know? And are you okay not knowing?’”

Apparently not. Even executives reluctant to take on the hard work of reversing disparities had to admit they were uncomfortable with willful ignorance, and Boyo worked with a team to lay the groundwork for an authentic equity strategy, beginning with an equity counsel. “It was important to me that we have 50 percent be frontline staff and 50 percent be executives or directors,” he said. The team came up with a mission and vision, which was to eliminate disparities and promote inclusion and community.

Studies indicate that persistent racism is a leading cause of stress.

“Experiences with racism keep Black people in a near-constant state of increased adrenaline and stress that wear on the body significantly” -Dr. Ayanna Bennett, SF's Director of Equityhttps://t.co/LC4iZuoiFP

— Zuckerberg SF General Hospital & Trauma Center (@ZSFGCare) September 4, 2020

Bake equity into every department

Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital serves more than 100,000 patients a year. Besides the hospital and trauma center, it oversees 15 primary care clinics and 20 research centers and offers offers “compassionate and culturally competent care” to patients in more than 20 languages. With this backdrop in mind, Boyo and team developed a blueprint for equity.

“We have three priorities with our equity strategy – number one is understanding our patients,” said Boyo. “Our goal here was to have 90 percent completion with race, ethnicity, language, data, and then to have 90 percent of our staff trained in sexual orientation and gender identity. Our second priority is what we call ‘eliminating disparities’. And the third is developing our workforce.”

To make sure everyone was involved, Boyo and team asked each of the 57 departments to stratify their number one quality metric by race and send the data to the hospital’s health commission and CEO for evaluation.

“This was our way to make sure that the whole organization was rallying around equity — a way to not let anyone off the hook and ensure that equity was not just a project, but a priority and a strategy for the organization,” Boyo said. “We made sure that we were getting every single person in the organization, even if you’re in environmental services or in biomedical engineering, all the way to department of surgery, to agree that equity matters and that you have work on equity. The CEO, COO or leader of the organization, too, has to be an advocate for the equity work. It cannot be a project. If it’s framed as a project, it is going to be very hard for it to be successful.”

In addition, staff engagement was essential. “If there’s one thing you take away from my talk today, it’s that when you’re doing equity work looking only at patient outcomes, that’s just one piece of the puzzle,” said Boyo. “You really need to understand what your workforce is experiencing because the research shows over and over again that staff engagement ties in with patient experience.”

Starting the equity journey

Boyo outlined the hospital’s equity journey over the last two years. When he began his role as equity strategist in 2017, only 6 percent of the SF General Hospital departments were breaking down their quality metrics by race, ethnicity or language. But there was a sea change after the new immigration policies, COVID-19 contagion, and an institutional commitment to equity – and a talk with departments that were not handing over their metrics.

“Now almost 70 percent of our departments’ data are stratified in metrics by race, ethnicity, and language,” said Boyo proudly. In August 2018, he noted, he had to have a “crucial conversation” when some departments failed to present their metrics. Referencing his slides, Boyo noted that “you can see a huge jump in September to a hundred percent. So this is how we’ve been getting everyone from the C suites to the chairs of departments involved. We’re an academic medical center, so the teachers and the department chairs have to buy into equity, because everyone has a role.”

There were surprises and non-surprises. In emergency medicine, Boyo and team learned that the number one project metric was “patients who left without being seen.” When the ER department broke that down by race, they found Latino patients had the highest rate of leaving without being seen.

“Then we started drilling into our security services, since equity doesn’t apply only to clinical areas and I oversee the sheriff department’s interactions at the hospital. We found out nearly 50 percent of the use of force by law enforcement were on Black patients, even though they make up only 17 percent of the entire patient population. So in my role as COO, I was drilling into that data and trying to understand what the driver was here.

“We had other interesting findings in our diagnostic imaging unit, where we found Asian-American patients had the highest no-show rates. We drilled into that data and found out that a lot of the reminder calls and letters were in English, so this gave us the opportunity to really close gaps in those areas.”

First time @ZSFGCare Trauma team has an African-American Attending, Fellow, and @UCSFSurgery resident on Trauma call. @TraumaDocSF, @JenReid_MD, Dr Frank Primus. #Savinglives, #Stampingoutdisease #Blackmeninmedicine, #Blackwomeninmedicine @UCSFODO, #ILookLikeASurgeon pic.twitter.com/MR1vQAJUwQ

— Dr. Andre Campbell, FACS, FACP, FCCM, MAMSE (@TraumaDocSF) September 7, 2020

Taking a close look at your workforce

Boyo said that something in his role as COO that he had really come to embrace was looking at the workforce as closely as he looked at patient outcomes.

“Now that we had a lot of momentum with our patients, we wanted to understand what our staff was experiencing. So breaking things down by race and ethnicity, we saw a discrepancy, especially when it comes to our Latino patients who happen to make up our largest patient population. Latinos are underrepresented in staff, and they are underrepresented in physicians. So the question becomes, how are we going to address this? And what is the benefit of addressing things like this, especially when we know that having an empathy bridge is more likely to have patients actually follow their care instructions?”

Boyo and his team led an equity survey, the first of its kind in the history of the hospital. In his talk, he shared some insights on two questions in particular. Responding to the statement ‘I have observed others disrespected for who they are at [the hospital in the following areas,’ 43 percent of those surveyed said that race was the number one aspect associated with disrespect. At the same time, 33 percent of the people that completed the survey said they had never witnessed any disrespect when it comes to culture, race, language, religious, political affiliation, sexual orientation, gender, age and ability.

“Those are very different worlds,” Boyo said. “So you have to ask yourself, what does it mean when you have a care team with someone who is from the 33 percent group and with someone who is from a 43 percent group, and they’re taking care of a patient? What happens when microaggressions take place? What happens when implicit bias is taking place? How do we bring people who are in very different ends of the spectrum when it comes to equity and perception of biases? What happens in that care team? And how do we address that before it becomes a crisis?

“So the question raised by the survey was, where is the hospital in our commitment to equity?” Boyo said. “When we look at equity by race, you can see that if you are Native American, Black or African American and Latino, over 50 percent in these groups felt that San Francisco General Hospital had a lot of work to do when it came to equity, right? But then if you look at other racial groups in the organization — if you looked at our white population’s view of equity in the hospital — almost 60 percent had a very different view. And the same thing applied to our Asian American population. And what I’d encourage everyone to think about is this: If your organization took this survey, where would you sit?” Download a copy of the survey.

“Creating a space to have difficult conversations”

Based on the feedback it had gathered, the equity team decided the hospital was in a transitional phase. The equity strategies the team would build into the workforce included making sure people received training on trauma-informed systems as well as training on implicit bias and inclusive environments.

“If you think about Martin Luther King’s dream, if structural transformation is what he strived for in the US — meaning that we’re living, breathing and walking equity – at the bottom is an institution that is just tolerant of people of color,” said Boyo. “Here at the hospital, we’ve focused on race because that was the number one aspect that people have perceived increased disrespect. Internal and external communications may declare we don’t have a problem, but this does not reflect the reality.”

“But beyond training, we wanted to create spaces where we can have very difficult conversations,” he continued. “So we have a workforce strategy on how to have difficult conversations, how to promote inclusion in our work, and we have a patient outcome strategy, which is really focused on our quality outcomes. That in turn is reviewed by the health commission and with coaching from leadership to make sure that all quality metrics are stratified by race, ethnicity, and language. So it’s very key that when you’re doing equity work that you also always have a workforce strategy. And, as I mentioned, the leader of the organization has to be an advocate for the equity work for it to be successful.”

De cualquier manera que decida disfrutar del clima este fin de semana de celebración, no se olvide mantener a sus seres queridos seguros.

40% de las personas con COVID-19 no tienen síntomas. Es mejor amar desde lejos para protegerlos. ¡Haz este día de labor un labor de amor! pic.twitter.com/3N8vzdxjcN

— Zuckerberg SF General Hospital & Trauma Center (@ZSFGCare) September 3, 2020

In his piece for Health Evolution, Boyo writes that he is inspired “by how health workers rallied at the height of the pandemic…. sharing data, resources, and practices…Imagine a world where we harnessed that resilience, then channeled it towards eliminating disparities.”

“During these harrowing times, I’ve appreciated the emotional support of white friends and colleagues,” he added. “However, I’ve struggled to answer the ‘How are you doing?’ conundrum. How do you convey the feeling of desolation when you’re reminded regularly that your life doesn’t matter?”

“For Black health workers, the desolation is exponential. Our lives are dedicated to a world we are the least likely to have access to, the least likely to heal in and the least likely to thrive by most indisputable metrics. In America, Black women are 3.3 times more likely than whites to die from pregnancy complications. Despite much uncertainty with SARS-COV-2, Black people are 2.4 times more likely than whites to die from COVID-19. Black health workers behold the aftermath of injustices upon Black lives. We lift the pain. We cradle the trauma. We embody their stories. We comfort and prepare them for the battles we know they’ll face when they leave the hospital or exam room. They are us. Every day, Black health workers wake up and choose to go into a world where disparities are pervasive and lethal. We stay in that world to re-write the narrative.”

Find this useful or interesting? We’re constantly sharing stuff like this. Sign up to receive our newsletter to stay in the loop.