The collaborative’s data and findings form the basis for the next phase of the state’s ACEs Aware initiative

Nearly 18 months ago, just as the pandemic lockdown began, CCI announced a learning collaborative called CALQIC to screen, treat and heal for adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, in partnership with the UCSF Center to Advance Trauma-and-Resilience-Informed Health Care – part of a statewide screening initiative that was complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

At CALQIC’s final session this September, Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, Surgeon General of California, praised its accomplishments during a time of unprecedented hardship. “I want to thank you all for this incredible hard work and partnership with the state,” she told participants via Zoom. The state would continue to build on CALQIC’s “extraordinary” work, she said, in the next phase of this work.

“All of you in CALQIC have stayed fully engaged in this work throughout the pandemic, throughout all the challenges with wildfires, all the drama and the stress of the political turmoil that has happened over the past year and a half,” Burke Harris added. “It’s really a testament to your dedication and to the incredible power of this movement.”

It was also a testament to the power of trauma-informed care practices, which helped most participants expand their trauma screening and healing during this time. At the September convening, the collaborative marked the end of its journey highlighting a relational approach to addressing childhood trauma and celebrated the remarkable progress and learnings among its participants, which included 15 organizations serving more than 250,000 Medi-Cal patients.

CALQIC’s work doubled the percentage of California clinics in the initiative participating in ACEs screening, from 41 percent to 82 percent by the summer of 2021 – a figure that climbed to 84 percent by the fall, according to evaluator Monika Sanchez of the Center for Community Health and Evaluation (CCHE), whose report on the collaborative collected data on thousands of screenings and interviewed staff at the participating clinics.

Why CALQIC centers respect and dignity in ACEs screening

The movement for childhood trauma screening has emerged because a landmark CDC-Kaiser Permanente study and dozens more have linked ACEs with an increased risk for a host of serious diseases and conditions across the lifespan, including cancer, depression, suicide, diabetes, substance use and heart disease.

The fallout from ACEs is also costly. Researchers have found the annual health-related costs of ACEs and toxic stress to California to be $112.5 billion a year, which includes both health care spending and “disease burden,” which includes premature death and years of productive life cut short by disability.

ACEs screening and treatment has the potential to lower the risk of chronic disease and keep ACEs from being passed from one generation to the next, according to the CDC. In addition, researchers like Dr. Robert Sege of Tufts University School of Medicine and others have found that positive childhood experiences, support, and strengths-based counseling from provider can reduce and even reverse the impact of ACEs and toxic stress.

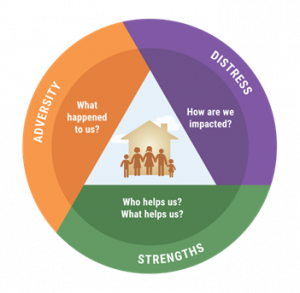

But ACEs screening done with little explanation — or interventions that seem patronizing or threatening — could backfire, experts say. To create a bridge to patients, the CALQIC team developed a healing approach based on trust, empathy, dignity, and mutual respect for ACEs screening and response in primary healthcare settings known as the TRIADS framework.

The TRIADS framework urges providers to explore their patients’ experiences with racism, discrimination, and maltreatment as well as their sources of resilience. “Patients with histories of adversity often experience healthcare and other systems as personal, judgmental, and harmful. For this reason, we believe that it is essential to conduct ACEs screening and response within a safe and caring healthcare team-patient relationship” and to focus on the patient’s strengths and healing, according to UCSF researchers.

TRIADs Framework graphic

Dr. Alicia Lieberman — a CALQIC leader, UCSF professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and director of the Child Trauma Research Project — helped develop the TRIADS framework in a way that allowed the patient to be a partner in their treatment plan. “We tell the patient they can opt not to respond to questions, and we’re very clear that they decide what kind of help they want,” she told CALQIC participants at an earlier convening. “This approach affirms the patient’s dignity because it is done with consent.”

At the September convening, Lieberman discussed TRIADS and observed that CALQIC frequently hear concerns that asking patients about adversity can be traumatizing. “What we’re finding is that the opposite is actually true,” she said. “Patients, as a rule, feel relief from shame and guilt when they learn that adversities are universal — and that we’re harnessing their strengths and resilience toward healing.”

CALQIC coaches and clinics share their stories

After a meditation led by Jackie Nuila of CCI, the discussion turned to program data and a powerful conversation that Dr. Ken Epstein, PhD, LCSW, facilitated with the CALQIC coaches and providers in a Wireside Chat. The discussion mirrored the same principles used by CALQIC providers talking with patients: an open, reflective discussion in which speakers were supported and affirmed. The group explored how trauma screening and response changed their relationships with patients, providers, and families, talking about their initial anxiety and stress over trauma screening as well as their joyful successes.

CALQIC final session

“Sometimes the residents will come in and they’ll have all the papers and questionnaires we have to ask and they’re just like, ‘Oh my god, I have two more patients waiting for me,’” said Dr. Eric Fein of the Los Angeles County Department Health Services. “It may be unsaid, but it’s like, ‘How do I get through all this? How do I cover this? So we say, ‘Okay, let’s take a step back: What has the patient been through? What kind of strengths does the patient have? What’s not going so well?’ And then they say, ‘Okay, I see, let me organize my thoughts around that.’ And through that repetition, they figure out how to how to move through clinic and build relationships. It’s about how to be therapeutic without being the therapist.”

Dr. Gina Johnson of Northeast Valley Health Corporation echoed this sentiment. “The commonality is that we’ve all faced trauma, big or small. None of us are able to say that life has been easy. So the word ‘resilience’ comes from our life histories, our family histories, and from our experiences in the world, and helps us to be stronger and more resilient.” (Look for a story on the Wireside Chat, which will be coming soon).

A clinic roundup on healing challenges, victories

In subsequent Zoom breakout rooms, clinics around the state reported how they rolled out screening during the pandemic. Some obstacles were physical — besides contending with the pandemic, one Southern California clinic was plagued by flooding on its top floor and had a car crash into its bottom floor reception room (after hours, fortunately). Others faced social challenges, including opposition to screening from exhausted nurses. But despite barriers, nearly all had made strong progress. Here are a handful of highlights from their stories:

LA County Department of Healthcare Services: More than 8,000 screens and 2500 referrals

Los Angeles County is one of the largest and most diverse counties in the US. “I’m most proud of our team, which as of this week has done more than 8,000 screens among the nine DHS clinics in the program and made about 2500 referrals to social and mental services,” said CALQIC lead Nina Thompson. “We’ve also trained 280 clinical staff in ACEs Aware and trauma-informed practices, including providers, nurses, nutritionists, clerks, community health workers and case managers.” She added that ACEs screenings have opened up important conversations with patients and trauma-informed care practices further strengthened that bond. To meet social needs such as food insecurity identified by the screens, LACDHS obtained a Network of Care grant to reach out to 700 community-based organizations in the county and are currently linking up patients to them through provider referrals and platforms like One Degree.

Santa Barbara Neighborhood Clinics: “Screening opened the door to seeking further treatment”

Santa Barbara Neighborhood Clinics

“Our team is so enthusiastic and empathetic – they show up for duty ready to do the right thing for our patients,” noted Ceylan Orkan, MSN, RN manager, of Santa Barbara Neighborhood Clinics. The health center was especially proud of the comprehensive training it offered its medical assistants, which allowed them to introduce ACEs screening in a way that made patients comfortable. SBNC also built an extensive data collection, loading patient data from screening into its Electronic Health Record (EHR), along with records of each patient’s family strengths, education about ACEs and protective factors, screening referrals and handouts. Providers also found adult screening turned up some important links, such a patient who came in for treatment for a substance use disorder. An ACEs screening and follow-up determined that he had experienced significant childhood trauma at age 7. “It was an example for adult providers of how ACEs screening really opened the door to seeking further treatment,” SBNC concluded.

Marin Community Clinics: “Including all the voices”

Marin Community Clinics

Marin Community Clinics has screened 3,000 people in obstetrics and 500 women who are pregnant for ACEs, as well as screening during well child visits. This success, noted MCC pediatrician Dr. Heyman Oo, “is really a testament to the fact that once you invest in people, these processes take on a life of their own.” For example, the medical assistant to the left assisting with screening (above), she says, is now head of nursing. The clinic has taken a collaborative approach to ensure that medical assistants have a voice in what they’re going to be doing. “Just working on ACEs has influenced other unrelated projects – we are more likely to say ‘let’s slow this down and include all the voices,” said Oo. “It’s also important to remember not to let the perfect be the enemy of the good.”

Borrego Health: Overcoming A Maze of Obstacles

Borrego Community Health

Borrego Health, which has clinics in San Diego County, Riverside, and the Inland Empire, faced a maze of obstacles in rolling out ACEs screening, including staff resistance, burnout, high turnover, lack of trust from caregivers, and language barriers. “2020 was one heck of a rollercoaster, and it bled into 2021 and nothing came out as planned,” said Healthy Steps program lead Lucy Aceves. But to increase staff buy-in, the team developed new trainings, outreach and workflows and is proud of their progress. “We’re really excited to see what that’s going to look like for our families,” Aceves said, “and we just really trying to mitigate toxic stress in these children, to hit it at the core.”

Family Health Centers of San Diego: “Walking the walk” in Arabic, Vietnamese, Cambodian, and more

Family Health Centers of San Diego

San Diego has a large Arabic population, and after embedding a script for ACEs screening in its EHR, Family Health Centers of San Diego had translated it translated into Arabic. The team has also translated an ACEs self-care handout into Arabic, Cambodian, Vietnamese, and other languages. “We’ve been so lucky to have had had excellent, engaged site champions that can serve as really safe people for the providers to share their challenges with,” said pediatrician Wendy Pavlovitch. “We are really working on walking the walk in this initiative and applying trauma-informed principles and support of each other, which is a different and new way for us to do things.”

Sonoma County Indian Health Project: “We want to get our community involved in treatment”

During the pandemic the Sonoma County Indian Health Project lost three licensed therapists, along with a psychologist and a psychiatrist who were working for the clinic part-time. It is now down to one licensed full-time therapist. To be able to work on ACEs screening and response, the team lead turned to their primary care provider and medical assistant. “Our population faces intergenerational trauma dating back to the settlement of California and the Gold Rush, and the displacement of tribes and traumas faced in that history,” said Kurt Schweigman .“So we want to educate all our staff about that, and to get the community involved” in treatment.

Santa Rosa Community Health: Everyone from front desk staff to clinical is trained in ACEs screening and response

Santa Rosa Community Health serves 40,000 patients, including some in homeless shelters, and runs 15 work groups about ACEs. One of the early adopters of ACEs screening, the health center’s pediatric and teen campuses medical director Dr. Deirdre Bernard Pearl has previously explained that the health center turned to their parent advisory group for counsel on the trauma screening. “The parents said they want someone kind and caring to give them a survey, and they want us to explain that everyone fills it out,” said Bernard-Pearl. “We can let the healing begin by letting both child and caregiver know that we will listen, and we will care.” At the CALQIC session, Carin Hewitt said that 95 percent of their clinical staff has done ACEs trainings, as well as every other department, including the front desk staff. “It has led to a deeper understanding of where our patients are coming from and our connection with them has been enhanced,” she said. “It has been hard work, but it has been pretty incredible.” Another important learning the team had, she said, is to apply trauma-informed principles to the whole and treat each other with compassion and self-compassion.”

Santa Rosa Community Health serves 40,000 patients, including some in homeless shelters, and runs 15 work groups about ACEs. One of the early adopters of ACEs screening, the health center’s pediatric and teen campuses medical director Dr. Deirdre Bernard Pearl has previously explained that the health center turned to their parent advisory group for counsel on the trauma screening. “The parents said they want someone kind and caring to give them a survey, and they want us to explain that everyone fills it out,” said Bernard-Pearl. “We can let the healing begin by letting both child and caregiver know that we will listen, and we will care.” At the CALQIC session, Carin Hewitt said that 95 percent of their clinical staff has done ACEs trainings, as well as every other department, including the front desk staff. “It has led to a deeper understanding of where our patients are coming from and our connection with them has been enhanced,” she said. “It has been hard work, but it has been pretty incredible.” Another important learning the team had, she said, is to apply trauma-informed principles to the whole and treat each other with compassion and self-compassion.”

La Clinica: “People whose voices don’t usually get raised are speaking up and blossoming”

Dr. Sara Johnson remembers Dr. Alicia Lieberman, in her first webinar for CALQIC, “saying that healing occurs in relationships. And that has been a deepening epiphany throughout the project. We’ve seen that we need to prioritize our resilience work at the clinic before we heal anyone else. We’ve integrated the domain of wellness into all our work – for example, when talking about intergenerational ACEs, we talk to our patients about how that impacts parents and children.” She also noted the clinic, which started as a close-knit storefront organization, now has thousands of employees across many counties. “We’ve seen people whose voices don’t usually get raised speaking up and blossoming as a result of this work, and that is really cool,” she said.

Northeast Valley Health Corporation: Treating trauma we would not have known about were it not for screening

Northeast Valley Health Corporation is a large federally qualified health center with 17 clinics. Their screening focuses on patients zero to five years old at the two-week visit, the 15-month visit and at the well-child exam visits yearly from two to five years old, as well as a small subset of adult patients at the Sun Valley Health Center. As a follow-up to one screen, providers talked with a mom who had recently migrated to the US with her children, who were now anxious, bedwetting, and showing other signs of trauma. It turned out, as the mother tearfully said, that she had been separated from her children at a shelter and sexually assaulted, and her children did not know where she was for several days. “If we had not done ACEs screening, we would not have known about that,” Carolina Aguilar said, explaining that they were much better able to help the family as a result.

Petaluma Health Center: All-staff ACEs trainings and virtual parenting groups

Petaluma was most proud of its trainings, which, occurring amid the pandemic and natural disasters, “was no small feat,” according to Director of Innovation Jessicca Moore, FNP. Besides hosting virtual parenting support groups, all their providers took ACEs Aware training and new hires trained in ACEs and toxic stress as part of onboarding. “Engaging with patients about ACEs isn’t as scary as it seemed,” she said. “For some patients, understanding the impact of ACEs can be the missing piece that helps them understand their lives and challenges.”

Eisner Health: “It takes a village”

Sometimes the most humble people in an organization can create the most transformational care, UCSF trauma researcher and professor Alicia Lieberman has said. Eisner Health leaders stressed this point when they talked about their pride in training all their employees about ACEs and toxic stress. “From people taking calls to the front desk staff, each person’s role really matters and makes an impact,” said trauma informed care coordinator Andy Fetzer of Eisner Health. “Our CALQIC coach was amazing, too, and her materials helped us tailor our offerings to our patients’ needs.”

The next phase: “Cutting ACEs and toxic stress in half in our generation”

Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, Surgeon General of California. Credit: Michael Winkur

Winding up the program, California Surgeon General Burke Harris reflected on the collaborative’s work during the pandemic year. She said she felt “a huge gratitude” due to CALQIC’s data and evaluation findings, which led the way for the next phases of the state’s ACEs Aware initiative.

“I love looking at data — anybody who knows me knows I’m a data nerd — and the preliminary data from your CALQIC clinics show that ACEs screening is feasible, acceptable, and considered valuable by providers and patients and families,” said Burke Harris, a pediatrician, researcher and author who has helped lead many studies on ACEs and has written a well-received book called The Deepest Well: Healing the Long-Term Effects of Childhood Adversity. “And because of your work, we’re also able to identify those challenges and those areas where we need to continue to invest. We need to continue to find solutions. We need California to work steadfastly toward the goal of cutting ACEs and toxic stress in half in our generation. And that’s what the next phase of ACEs Aware is going to be about.”

UPDATE: Providers may also want to check out the evaluation of our CALQIC program. This report by the Center for Community Health and Evaluation (CCHE) presents findings from the initiative-wide evaluation that spanned across all 15 organizations and 48 clinic sites participating. It used a mixed methods approach to understanding progress, facilitators, and barriers, including quarterly clinical data reporting, a clinic capacity self-assessment, interviews with clinic representatives, and document review.

Related resources

The TRIADS Framework home page. University of California at San Francisco.

Roadmap for Resilience: The California Surgeon General’s Report on Adverse Childhood Experiences, Toxic Stress, and Health. Nadine Burke-Harris, MD, and the Office of the Surgeon General. December 9, 2020.

ACEs Aware, an initiative of the Office of the Surgeon General of California.

Watch: What Does It Mean to be Trauma-Informed? Center for Care Innovations.

The TRIADS framework: An Approach to Understanding, Helping and Healing People Who Experience Trauma. An introduction by Dr. Alicia Lieberman.

Tackling Childhood Trauma During a Pandemic: Lessons from California’s Largest Collaborative on ACEs Screening and Response. Center for Care Innovations. April 7, 2021.

The Journey Toward a Healing Organization: 10 Steps to Transform a Traumatizing Workplace. Center for Care Innovations. Feb. 1, 2021.

From Wildfires to Childhood Trauma, A Resilience Collaborative Transformed the Way Clinics Face the Unthinkable, Center for Care Innovations. November 9, 2020

“Widening the Health Care Lens”: Lessons from CALQIC’s Opening Session on Trauma and Healing. Center for Care Innovations. Oct. 20, 2020.

Find this useful or interesting? We’re constantly sharing stuff like this. Sign up to receive our newsletter to stay in the loop.