It might seem as though nonprofits, clinics, and hospitals working to prevent and heal childhood trauma would be especially sensitive to trauma, burnout, and toxic or abusive behavior at the workplace. Unfortunately, this is not always the case.

In reports from the field, we have learned that even some organizations that are the most passionate about ending childhood trauma have proven to be authoritarian and exploitative in dealings with employees. This type of workplace is known as “trauma-organized” — one in which abusive behavior is reinforced and re-enacted.

On the continuum to a healing organization, this workplace is at the starting line. Its traumatization of employees, however unintentional, tends to result in burnout, low morale, and high turnover — something that can spill over into its work with clients. How can its employees and leaders change the organization into a trauma-informed workplace – and eventually transform it still further into a healing organization?

Irene Sung, MD, has had considerable experience in such journeys. Her career has included serving as a child and adolescent psychiatrist and as a recently retired executive leader at the San Francisco Department of Public Health, which praised her for leading the network’s behavioral health services through major changes and navigating challenges “with grace, wisdom, and compassion.” A coach and consultant for the Resilient Beginnings Network, a joint project of Genentech and the Center for Care Innovations, Sung recently talked to participants about the journey to a healing workplace, its joys and challenges, and some crucial steps to get there — including creating time for reflection, respecting dissent, and celebrating diversity.

From Trauma-Inducing to Trauma-Reducing

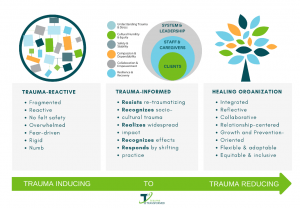

Sung began by discussing the three kind of organizations on the continuum from a trauma-inducing to a trauma-reducing workplace (see chart below):

Credit: Trauma-Transformed

On the left is the trauma-organized workplace, where leadership tends to be authoritarian, leading workers to feel hopeless, fearful, and powerless. Emotional numbing is common, as well as an “us vs. them” mentality, according to Sung. As one human resources organization put it, such workplaces create an environment “that chips away at workers’ sense of security, self-worth, health, and well-being.”

A trauma-informed workplace, in contrast, is invested in collaboration. Employees not only have a shared understanding of trauma and paths to recovery, they have a shared language to talk about it. There is a shift from asking (or thinking) “What’s wrong with you?” to asking “What has happened to you?”

Staffers are also likely to be trained in guidelines known as “the four R’s” in mental health circles: realize the impact of trauma and pathways to recovery; recognize the signs of trauma in clients, family, and staff; respond with supportive policies and procedures; and resist re-traumatization. Anyone who has been traumatized by a secretive authoritarian workplace will find its guiding principles especially gratifying: safety, trustworthiness and transparency, peer support and collaboration, and empowerment, as well as an awareness of cultural, historical, and gender trauma.

But with an emphasis on doing rather than reflection, even trauma-informed organizations can make unintentional missteps that undermine healing. Sung recalls a colleague who told her that in one behavioral facility the staff used locked rooms for teens who needed a respite in a safe space. As a result of personal and community trauma, however, the teens were alarmed, even terrified, at being locked in. “It was a trusting place, so the leaders told them, ‘We’re going to open the doors – you’re not going to be locked up anymore,’” Sung recalls.

A healing organization is the last step in this continuum: a workplace that consciously strives to be a place of healing. Leadership is supportive and relational (relationship-based). It is reflective and oriented toward growth and prevention, continually seeking to make meaning out of the past. A trauma-informed organization, it is collaborative, empathetic, and focused on equity and accountability. According to Raj Sisodia, co-author of The Healing Organization, this type of workplace “can alleviate suffering and elevate joy in our lives. [It] is a place of healing for employees and their families, a source of healing for customers, communities, and ecosystems, and a force for healing in society, helping alleviate cultural, economic, and political divides.”

A New Way of Seeing

So how can we help our workplace change from a place that is causing us trauma to a healing organization?

Irene Sung, MD

Transforming such a workplace into a healing organization involves a new way of seeing, according to Sung. “At most jobs we are not paid to reflect; we are paid to do,” Sung says. “We need the time for reflecting before we move into doing. But first comes seeing.”

Sung attributes her own close observation in part to growing up in an Asian immigrant family in the Midwest: “Surrounded by a culture not my own, I learned early on how to pay close attention to it.”

Small wonder that by paying close attention to the interactions at work, she deciphered their unspoken rules: “One was a small clinic in which you had to say hello, chat about the family or other things before you got into the business of the day; if you didn’t, the conversation didn’t go very well,” Sung recalls. “At another, larger organization, [conversation] was on your own time, not the organization’s time. To get change or even be heard, you had to threaten to leave…So in any group, it’s important to observe what is going unsaid.”

10 Steps Toward a Healing Workplace

Sung has worked closely with the Oakland-based organization organization Trauma Transformed, which works to ensure systems of care are “trustworthy, compassionate, coordinated, and responsive” to the needs and priorities of communities. Here are some elements of a plan she adapted there to set the stage for movement toward a healing organization.

1. Observe carefully

Look at how people interact at work. You’re familiar with your workplace’s code of conduct, but what are the unspoken rules? That may be integral to its transformation. “Think about what you need to support a change when it comes to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) work,” Sung says.

2. Create a space for reflectioN

Pay particular attention to anything you observe at work that nags at you or bothers you, Sung advises. Reflective leadership also means being present, thinking about your interactions with people, and applying those insights to the future. “It’s a chance to get out of your head a little bit and think about your impact on others,” she says.

3. Welcome curiosity (internal and external)

Curiosity makes it easier to allow dissent, according to Sung. “It’s important to listen without getting defensive,” says Sung. “Instead, we can say, ‘Tell me more about that.’”

4. Encourage accountability in group discussions

In group discussions, it takes courage to lean in and share your thoughts and also the strength to lean back and listen, Sung says. “There are often some people who dominate the conversation,” she acknowledges. “Interestingly, research suggests many people who talk a lot report that they don’t feel heard. So if you’re leading a discussion, you might summarize what you’ve heard by writing it down it on a big whiteboard and asking the person, ‘Is this what you mean? Ok, great, this is captured here’ — all responses that make the [talker] realize they don’t have to keep going. You can also encourage quiet or more introverted colleagues to talk by saying, ‘Is there anyone we haven’t heard from?’” If some people are still reluctant to join the discussion, she says, adding a chat box can help.

5. Offer compassion for yourself and others

“Sometimes things we talk in a group bring up a lot of emotion, and we shouldn’t ignore it,” Sung says. “We should make space for emotion and acknowledge it, pay attention to it. A compassionate response could be as simple as telling the person, ‘This is really challenging’ or ‘this must be really hard.’ Avoid creating a ‘hero culture’ in which people aren’t free to acknowledge their exhaustion.”

6. Assume good intentions, but address impact over intent

This discussion has come up frequently in terms of microaggressions. For example, a provider may repeatedly mispronounce an immigrant colleague’s name after being told how to pronounce it; when confronted about it in private, he may insist he had no intention of hurting his colleague. “The idea [of addressing impact] is that the problem isn’t ignored,” Sung says. “If you step on someone’s toe, for example, you may not have meant to hurt that person, but you take responsibility for doing so. Similarly, it’s realizing something you did or said unintentionally hurt someone and having the courage to hear that and take responsibility for it.”

7. Celebrate diversity

“This whole year has been about recognizing inequities and divisiveness, while becoming more aware of the diversity in how we think and community,” Sung says. “What I’d say is there’s still a lot of work to do, especially around gender, sexual orientation, and racial diversity. For example, in the dominant culture, the typical ‘pause time’ in which one person stops talking in this country and another starts is one second. In some Native American cultures, a colleague told me, the typical pause time is three to four seconds. So unless this is group knowledge, some people might continually get cut off while waiting to join a conversation.”

8. Integrate perspectives

Know that everyone has a piece of the puzzle, including providers, pharmacists, staff, and patients. In one case, Sung remembers learning about a higher risk of death associated with a particular medicine being prescribed to patients addicted to opioids. Doctors and pharmacists were bitterly divided on the issue, with shouting matches erupting on phones and in meetings. Sung persuaded the two groups to work things out by talking with each other and others involved in the issue, and it worked: “Six years later, we still had no deaths [related to that issue].”

9. What is learned here, leaves here. What is said here, stays here

In group sessions in which colleagues need privacy to talk freely, it’s agreed that they should not be quoted or identified without their express permission. However, the lessons learned can be shared with a wider audience.

10. It’s okay not to have all the answers

Even a healing organization is constantly reinventing itself. “It’s also important to know that a healing organization doesn’t mean it’s an organization where everything is running smoothly and there is no stress,” says Sung. “Leaders still have to give directives, and that may cause new stress. What it means that you’re aware of the stress and its impact and you are paying close attention to it.”

Find this useful or interesting? We’re constantly sharing stuff like this. Sign up to receive our newsletter to stay in the loop.