Who Should Watch This Video?

Everyone — but especially health care providers who work with immigrant and refugee patients, many of whom have suffered war and terror in their home countries before making the perilous journey to the United States. The film documents the power of local community clinics that partner with community health workers, interpreters, and immigrant groups to help refugees heal from trauma and enrich our country with their presence.

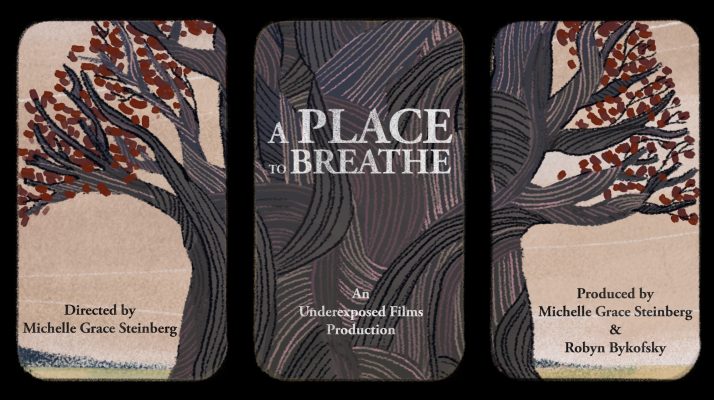

“A PLACE TO BREATHE explores the universality of trauma and resilience through the eyes of immigrant and refugee health care practitioners and patients. This feature-length documentary intertwines the personal journeys of those who are transcending their own obstacles by healing others. Combining cinema vérité and animation, the film highlights the creative strategies by which immigrant communities in the U.S. survive and thrive.”

–Director Michelle Steinberg

“A Place to Breathe”

A stylish Cambodian manicurist in a tiny Massachusetts salon. A woman in traditional Guatemalan garb strolling to a clinic in Oakland, California. A large African family walking through an airport, laughing and excited to finally arrive in the United States.

Nothing seems out of the ordinary, but you never know what someone is going through. That’s one of the messages driven home in the extraordinary documentary “A Place to Breathe,” as we find that these refugees — from Cambodia, Guatemala, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo — have experienced near unimaginable horrors in their home countries: Fleeing for their lives as soldiers set fire to their village, starving in the killing fields of the Khmer Rouge, forced to watch family members tortured and abused. But as they settle into their new lives in the United States, we see them slowly healing as they work with — and sometimes for — two remarkable community clinics: the Street Level Health Project in the Fruitvale neighborhood of Oakland, and the Lowell Community Health Center/Metta Health Center of Lowell, Massachusetts.

A Cambodian festival in Lowell, Massachusetts

The award-winning film — hosted by the Resilient Beginnings Network of the Center for Care Innovations — offers a look at three immigrant families so intimate and natural that it feels like breathing. We listen to family conversations, watch Edgar and Yania, a young couple from Mexico and Uruguay, do outreach to Latino and indigenous day laborers and lead them in Spanish-language yoga classes (one of the many highlights of the film). Edgar and Yania’s dreams of becoming a nurse and social worker are under constant threat of deportation due to changes in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), or the “Dreamers” Act, but they persevere. At the same Fruitvale clinic, a Guatemalan immigrant interprets for patients who speak Mam, an indigenous Mayan language. “At home, there is tremendous discrimination; we cannot even ride the same bus with Ladinos,” she says.

On the other side of the United States., we meet Rodrigue, a refugee from the warring Republic of the Congo who lives in Massachusetts in tight quarters with his mom and six siblings and is studying to become a community health worker. We’re also introduced to Socheat, a Cambodian who escaped the Khmer Rouge and is working long hours to support her family on a manicurist’s salary, and other members of Lowell’s thriving Cambodian community

Scene from the Street Level Health Project

We get glimpses into the everyday humiliation and pain of some asylum seekers: Weeping inconsolably, one older Guatemalan woman tells a clinic worker that the ankle bracelet that US immigration officials have forced her to wear for four years hurts her and has affected the circulation in her foot; she is also ashamed to go outside “because people see it and look at me as if I’m a criminal.” But there are victories, too: A clinic doctor who documented the damage to her foot was successful at persuading immigration officials to have the ankle bracelet removed.

The film presents refugees’ backstories in a way that doesn’t inflict further trauma by having people relive those memories on camera. Instead, terrible memories are handled through animation, whose exquisite, dream-like quality and quiet voiceovers convey pain and horror without triggering the subjects or the audience. We watch anxiously as tension builds over the course of the narrative arc: Will Edgar be deported? Will Rodrigiue and his family be reunited with his sister, who authorities in Africa forced the family to leave behind? Will Yania be able to finish her coveted nursing degree?

“The film was inspired by the incredible resilience that we see in our patients and the wisdom that comes with that resilience,” said director/producer Michelle Grace Steinberg, MS, who has worked for 12 years as a nutritionist and herbalist at the Street Level Health Project. “The film was really inspired by years of seeing what my patients have done in terms of their own healing and what my colleagues who have been through these experiences bring to the table. I’m hoping it can serve to democratize medicine and get rid of some of the hierarchies we see there that have traditionally prevented community wisdom from being centered in culturally responsive, patient-centered care, particularly around trauma.”

Panel Discussion: A Place to Breathe

On June 29 we hosted a panel discussion about the documentary that featured filmmaker and Street Level Health Project nutritionist Michelle Grace Steinberg of Underexposed Films; Mam community health worker and interpreter Maria Vincente of Guatemala;, and yoga instructor Yania Escobar, formerly of the Street Level Health Project, as well as Dorcas Grigg-Saito, CEO of the Lowell Community Health Center; and Zarin Noor, a pediatrician at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland Primary Care clinic.

RBN panel participants included Sheshashree Seshadri from Bay Area Community Health; Alfonso Apu from Community Medical Centers in Stockton, California; and Omoniyi Omotoso from the Berkeley-based Lifelong Medical Care health center. (You can access a fuller version of the panelists’ backgrounds here.)

6 Key Takeaways

1. To be a community health center, you need to be part of the community

“I always say to people, the thing that makes community health centers different is the community, and that if we’re not out in the community working and and really being a part of it, then it’s hard to be a community health center,” said Grigg Saito of the Lowell Community Health Center/Metta Health Center. Over the years, she said, she has felt lucky to have seen the way her community health center has responded to the needs and the strengths of the Cambodian community as well as new populations of refugees from disparate places, including Iraq, Guatemala, Myanmar, Burma, Bhutan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. “People who come here as refugees and immigrants are accepted and valued,” she said. “And in addition to receiving the physical, the mental and the spiritual health care that they need, you may remember from the film that “Metta” means ‘loving kindness,’ and I think both our center and the Street Level Health Project have loving-kindness at their core.”

2. Be flexible and humble when working with patients, especially those who have suffered trauma

Animation images from “A Place to Breathe”

“If I were to pull out one line in the film that summarizes the emotion and energy behind both my practice and what the film was meant to convey, it’s really that you need to be flexible, humble and have the humility to listen to patients – to really show up and have deep, active listening,” said Steinberg. At the Street Level Health Center, she said, everyone works as a team.. “Often I’ll be working with patients around diet, exercise, sleep, and stress reduction, which I think are often ways that trauma shows up that aren’t always identified,” she said. “But I’m very careful not to necessarily reopen somebody by talking about their trauma story in a way that could be retraumatizing, unless that is a choice they make. We need to treat people the way they want to be treated, not the way we want to be treated. ..It’s always with the idea that there’d be a warm handoff to a mental health provider, if they need follow up on that.”

3. Cultural humility is crucial

Sometimes refugees and other immigrants prefer their own ways of dealing with mental distress over those of U.S. medicine. “We do not have psychologists or yoga in Guatemala; we vent our worries through religion,” said Maria Vicente, a Mayan nurse from Guatemala who works as an indigenous translator at the Street Level Health Project. “We pray to God and get rid of everything, making us feel much better and relieved. We go to church, light candles or kneel in front of our [religious] images. That helps us relax…. Providers need to listen respectfully, without judging, so we can provide a relaxed and safe place with no fear.” Support groups where people speak the same language are also important, she added. “This is helpful because sometimes, people cannot express themselves even though they try. They are scared. We feel that we don’t say as much as we want to, and it is very painful when you have experienced such strong trauma.”

4. Remember that life in the United States can also be traumatizing to immigrants

“For some people, life in the United States offers challenges that are as great or sometimes greater than what they experienced in their home country,” said Saito. “Post-traumatic stress syndrome, or PTSD, is a natural response.” It was a relief for some patients to tell their story at the clinic, she said. The health center offered weekly meditation services, after which patients could talk about whatever was on their minds, as well as women’s groups and community activities such as group walks or apple picking. “These kinds of everyday activities were often the vehicle for opening people up to talk about their stories,” she said.

5. Create time for self-carE

It can be excruciating for Yania Escobar of the Street Level Health Project to talk with immigrant patients who are about to visit their families, especially as she has been unable to see her beloved family in Uruguay for many years due to the uncertainties surrounding DACA. “Patients and I will be speaking Spanish and then they’ll turn to me and ask, “So when are you going back?” Often, after she gets the patients ready for their trip home, she asks a trusted coworker if she can take a quick break. “Being to do that without being asked too many questions has been a great resource for me in the moment,” she said. “And then at home, processing and journaling, meditating, praying — whatever somebody has in their practice — it’s all very, very important, especially when people do things that just hit a tender spot.”

6. Involve community health workers and interpreters in patients’ treatment plans

Michelle Grace Steinberg, MS

“Probably the most important piece to me is having community health workers and interpreters as partners in the treatment plan and in how we’re thinking about things,” said Steinberg. “Not just relegating their contributions to [interpretation or outreach], as if their wisdom doesn’t extend beyond that. I think the more that we can work as teams that have mutual respect, the more that respect will translate into creating jobs and structural places that hold what people are bringing to the table. And the less that we work as a hierarchy that sort of posits admin and MDs at the top, the better chance we have of actually recognizing community needs. Team-based care that has an awareness of cultural and structural and social factors is really how I see addressing trauma.”

Resources

Resources for asylum seekers in the U.S.

Find this useful or interesting? We’re constantly sharing stuff like this. Sign up to receive our newsletter to stay in the loop.