Patients with hearing difficulties can face serious obstacles in healthcare settings. “I am hard of hearing and struggle to understand what my doctors are saying. It’s embarrassing for me to ask them to repeat and speak louder, so I often just nod my head,” notes one patient from Pueblo Community Health Center in Colorado. “Once I had a follow-up appointment with my doctor after some testing, and my doctor said they were referring me to a hospitalist. I did not hear him correctly and thought he said I was being referred to hospice. Two days went by before I found out that I was not going into hospice care. Those were stressful, worrisome, and lonely days.”

Pueblo Community Health Center

That’s the kind of health access fail that can make healthcare providers wince. And yet a range of alternative communication tools can make a world of difference—for patients and practitioners alike. No deaf or hard of hearing patient should miss out on key information or struggle to connect with their healthcare team. But they often do. In some cases, deaf or hard of hearing patients may avoid important medical care because of communication impediments. They may also abstain from care because of pride, shame, or stigma, not letting on that they can’t understand what’s being said.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Pueblo Community Health Center wanted to improve equity and quality of care for its deaf and hearing-impaired patients by providing more ways of communicating with patients at each point in the healthcare process. So in early 2022, as part of CCI’s Colorado Health Innovation Community, the center set out to identify barriers to care for deaf and hard of hearing patients, brainstorm solutions, and eliminate obstacles to care for this demographic.

The issue was first brought to the attention of the health clinic by a nurse practitioner with direct experience assisting patients with a hearing disability. As the organization delved into the problem, it discovered that staff in all sectors of the health center reported that this was a common concern. To get a better understanding of the problem, the health center conducted a staff survey. Survey areas included registration, clinical, pharmacy, lab, and behavioral health services. Respondents included employees in medical, dental, behavioral health, finance, operations, and administration.

Of the 123 health center employees who responded to the survey, 47 percent experienced difficulty providing care to deaf and hard of hearing patients. And 33 percent responded that they did not have adequate resources to improve communications with them. “We wanted to get a sense of how widespread a concern this was,” explains chief dental officer Levi Murray. “And we discovered it was pretty prevalent. We also learned that while we already had some tools in place to address this issue, some survey respondents weren’t aware of them. So we knew we had work to do on both ends.”

Pain points proved surprising—and widespread

Since 1983, Pueblo Community Health Center has provided primary health care services to patients in need in this desert community, 100 miles south of Denver. The organization is the only federally qualified healthcare center serving all of Pueblo County as well as the surrounding counties to the east, west, and south. The health center serves many low-income residents, including a high percentage who have incurred medical debt in collections. Around half of all Pueblo residents are Medicaid eligible. In 2022 the health center served 24,077 patients, provided more than 90,000 medical visits, 13,000 dental visits, and 13,000 behavioral health visits. Staff also delivered 475 babies.

To tackle the issue of deaf and hard of hearing patients, a team of five, including Murray, were designated to lead the charge. The group, which included three providers with face-to-face contact with patients, and two operational staff members, initially assumed the main pain point would be difficulty communicating during direct care interactions between deaf and hard of hearing patients and their providers in medical, dental, and/or behavioral health.

But that’s not what they uncovered. The difficulty in communicating with deaf and hard of hearing patients was reported by health center employees at all levels of care, including the front desk, billing, and medical assistants. Given that finding, it made sense to engage all these stakeholders in the brainstorming and testing of solutions and gathering feedback in the field.

The center also suspected it would be challenging to identify patients in need of these services, since they may not have reported their disability. Murray notes some patients may be reluctant to concede that hearing is a challenge. Others may not want to seem burdensome, and still others aren’t even aware that hearing loss is undermining their ability to access services. “We struggled to get the patient perspective as we embarked on this project, which would have been valuable,” says Murray. “In an ideal world, we would have had that input at the start.”

The federal government provides interpreters free of charge to eligible clinics. (Andrew Angelov/Shutterstock)

As part of the federal Americans with Disabilities Act, health care providers have a duty to provide communication aids and services to people with disabilities, including patients with communication (hearing, speech, vision) disabilities. The health center consulted with the Colorado Commission for the Deaf, Hard of Hearing, and Deaf Blind, which talked with team members about the resources available for medical settings. As part of that knowledge share, the organization learned that as a designated rural healthcare provider, the center is eligible for free interpretive services through the state. These proved somewhat limited and require advance planning, but they have been used by the organization as needed, notes Murray. However, the clinic had many more solutions to test out.

Improving patient and provider satisfaction

Early on in this project, the healthcare center learned about obstacles to providing quality care experienced by staff and deaf and hearing-impaired patients. It can start with the first phone call to schedule appointments or when a patient first heads to the reception station. Being able to communicate effectively and privately at patient check-in and check-out is important. The sharing of sensitive information, including patient health details, scheduling information, and billing data at the front office, can be especially difficult. Hard of hearing patients who need the reception team to speak at elevated volumes and repeat information multiple times to understand experience exposure of sensitive, private information. Deaf patients who rely on lip reading to communicate experienced a major barrier when masks were mandated during different periods of the COVID-19 pandemic peak.

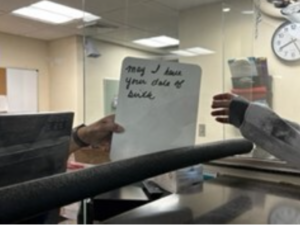

Simple, inexpensive and easy to use, whiteboards proved to be one of the most popular tools for patients and providers alike. Masks with a clear window for lip-reading were another favorite. (Courtesy: PCHC)

White boards and dry erase markers proved a hit with patients and reception team members alike. They’re used to communicate with patients by writing down questions which patients can respond to verbally or in writing. This is an effective solution since white boards are readily available, inexpensive, require no user training, and do not require charging or present other complications that can occur with electronic devices. Sometimes, it turns out, the best solutions are simple and low-tech. As one receptionist team member noted: “If I had known it was this easy I would have asked for these a long time ago!”

Surgical grade masks that incorporate a clear window that make a speaker’s lips visible also proved popular. These masks were in demand at reception stations and in the pharmacy at the pandemic peak. For many patients who have lost their hearing over time and do not utilize American Sign Language (ASL), lip reading is the primary way they are able to understand what is being said to them, explains Murray.

Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians found these masks especially helpful with hard of hearing patients who may struggle, for instance, to understand medication instructions. The masks were also useful in lab services and behavioral health settings. “We had a lot of positive feedback from patients regarding being able to see our mouths,” says pharmacist Rayna Corbin, who adds that patients appreciated not having to press their ear to window slots to understand and health team members didn’t need to raise their voices to be understood. The see-through masks allow for a greater ease of communication and a better sense of connection between patient and provider.

Signage posted at the Pueblo health center wherever patients interact with the staff (Courtesy: PCHC)

Simple signage at reception stations alerting patients to the availability of additional resources for deaf and hard of hearing patients have also proven useful. The health center created a decal and placed them on glass partitions at reception, lab, and pharmacy that read: “Are you having trouble hearing? Please let the receptionist know.” From previous experience, center staff know that many hard of hearing patients often do not alert staff members when they are having trouble hearing and simply nod in response to staff communication.

The center has high-tech solutions available too. The organization offers a patient-facing speech-to-text platform via tablet that is available for use at reception stations. The tablets feature connected microphones in an attempt to create real-time closed captions for deaf and hard of hearing patients. This solution is less user-friendly than white boards as tablets need charging and require secure storage and must be retrieved from a locked safe; in addition, the software transcription is not always accurate. As these devices become less cumbersome and translation software improves, they may become more sought after, notes Murray. “The talk-to-text iPads are bulky and sometimes transcribe incorrect information,” reports reception team member Leticia Bueno. “Patients are more responsive and like the ease of the white board. I have used white boards quite a bit and found it easier when I used two at the same time.”

Sometimes the simplest solution is best

After the team investigated and tested out multiple solutions, the innovations that stuck were generally simple and focused on improving communication at multiple points of contact. Tablet translation services were less popular but also in the mix.

“These solutions proved successful to various degrees and seemed to be largely tied to ease of use,” Murray explains. “Simple, low-tech solutions like clear masks and white boards were rapidly implemented and incorporated by employees. More complex solutions like workflow evaluation and patient portal use take more time and effort but will likely produce wider positive results as well.”

The health center introduced a new patient portal early in 2023 and looked for ways in which it could be leveraged for patient communication. Specific to the CHIC project, staff connected with the operations department to discuss portal messaging, texting, post-visit instructions, lab results, and follow-up recommendations. The patient portal promises some relief since clinic phone calls with deaf and hard of hearing patients are often difficult and frustrating for both parties. The use of the portal – still in its initial stages – is likely to expand.

Another area of exploration was how to identify deaf and hard of hearing patients. Workflows were modified to include the early identification of deaf and hard of hearing patients so these disabilities are now “flagged” in the electronic health record, which can include a note on what accommodations have been made in the past. This is ongoing across all departments.

A written exchange between a health care employee and a deaf or hard of hearing patient in Pueblo Community Health Center

Of course, none of these innovations are of any use if staff don’t know about them or don’t know how to use them. So the health center has also worked to make staff aware of what resources are available and offered orientation or training as needed, including knowing how to access tools such as virtual and in-person sign language services.

As for next steps, some limited anecdotal feedback has been collected by frontline employees, but more engagement with patients would be valuable, says Murray. Now patients are being identified for a patient survey that could prove a useful exercise to evaluate successes and shortcomings. A follow-up survey with staff gathering data on the efficacy of the solutions on offer is also in the works. On the logistics side, supply chain shortages during the height of the pandemic limited the availability of clear masks to test. Should widespread masking return, the health center would welcome testing several styles of transparent masks to determine the best fit. If a patient’s primary language isn’t English or ASL, that adds an additional layer of complexity in terms of translation and transcription services that was outside the scope of this project and requires more investigation as well, notes Murray.

That said, both providers and patients have expressed appreciation for the enhanced services. “There’s a lot of job satisfaction and fulfilment knowing that my hard of hearing seniors are having an improved experience in our care,” says Murray. “They really feel like their needs are being met.” Adds a Pueblo Community Health Center patient: “Using the patient portal is so much easier for me to connect with my doctor and get information after a visit. It means a lot that the health center is working to make the process easier for deaf and hard of hearing patients like me.”

Lessons Learned

Explore ways to build community from the get-go. Find reliable avenues to connect with deaf and hard of hearing patients. This would have been helpful in exploring barriers as well as evaluating possible solutions.

Confirm patients’ accommodation needs ahead of time. Make sure an interpreter is available and ready before the patient arrives. To help reduce stigma, ask all patients if they have a disability. Remember: Some disabilities are not immediately apparent.

Provide multiple resources for health team members and patients. Start with easy fixes such as white boards and signage. Have an ASL interpreting service on speed dial, use clear masks for lip reading, and stay abreast of the latest assistive technology.

Ask patients for their preferred form of communication. Not all patients who are deaf or hard of hearing use ASL. Don’t assume every patient uses the same accommodation.

Conduct staff training. Make sure all employees are aware of the tools and resources on hand to assist with communicating with deaf or hard of hearing patients.

Identify metrics of success at the start. Gather quantitative data at the outset; otherwise, it’s difficult to measure improvements and outcomes.

Find this useful or interesting? We’re constantly sharing stuff like this. Sign up to receive our newsletter to stay in the loop.