Whenever a tech innovation moves into the mainstream, vulnerable or marginalized consumers often get left behind. So when telehealth began to become routine during the pandemic, the Multnomah County Health Department, the largest federally qualified health center in Oregon, wanted to make sure that its Portland patients who were Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) had equal access to such services and didn’t get left behind. That’s important because, as one news story headline noted early in the pandemic, the future of health care in Oregon is largely virtual.

Part of the logo for the Multnomah County Health Department (Credit: MCHD)

The Multnomah County Health Department (MCHD) has seven primary clinics, one HIV clinic, nine student health centers, seven dental clinics, and seven pharmacies. It’s a complex and diverse public health system with more than 92 languages spoken by its clients.

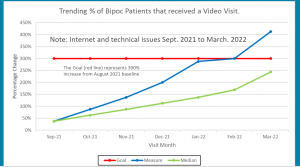

As part of CCI’s Virtual Care Innovation Network, MCHD wanted to conduct a pilot project to increase remote patient visits among its Black, Indigenous and people of color population. When the county health department started the pilot, none of the BIPOC patients at the department’s clinics were served by telemedicine. By the end of the reporting process for the program, in April 2022, the clinic had 21 patients who had participated in remote medical appointments. That’s a 300% increase, or quadruple the number of clients accessing telehealth—well above the goal of five each for the two different virtual appointment options the department offers.

MCHD chart showing how completed telehealth appointments quadrupled during the VCIN program. Credit: MCHD

MCHD uses the mobile medical app Doximity and the online patient portal OCHIN MyChart (in conjunction with the web-based video platform Zoom). During the pilot, they conducted 14 Doximity visits and 7 MyChart visits. And while early connectivity issues saw around only a third of telehealth appointments completed, that number had jumped to over 75% by the end of the pilot project.

That’s an impressive win. That said, it was hard won, with plenty of obstacles along the way. Still, the program now serves as a model for other clinics eager to provide equitable virtual care, says Lynn Schulman George, integrated clinical services project manager at MCHD, who partnered with IT experts, clinical systems information staff, and health team providers to work through the kinks to implement this program.

“That clinic has solved a lot of the technical issues that can impede this kind of program, and those learnings can be applied elsewhere in our system,” says Schulman George. “We grew our provider pool—more of the staff are now comfortable providing virtual visits—and we have new tools for patients and providers to access the technology that’s appropriate for their needs.”

Beyond the barriers

The Multnomah County Health Department surveyed 70 BIPOC clients to get a handle on what kind of barriers they faced to accessing virtual care. The biggest impediment: having the proper tools and the skill set to successfully navigate a telemedicine visit. Some patients didn’t have a smartphone or weren’t familiar with downloading mobile apps. Others lacked access to the Internet. Some, especially seniors, expressed discomfort with conducting health care visits this way. They worried about security and privacy concerns. Others were stymied by what to do if they experienced connection issues, a call dropped out, or the program crashed mid-visit.

Most young people today are born and raised with technology as part of their lives, notes Schulman George, even if access is an issue. But with some clients—particularly older patients—there was a fear factor that could be summed up as “too fancy, too soon.” Some patients also expressed frustration around the need to email, text, download, and use more than one app.

All duly noted. To take a deeper dive into the concerns that come up around remote healthcare appointments, the team interviewed five patients and five providers. They found that some clients and staff didn’t even know that telehealth was an option. So the department knew early on it needed to do a better job on education, training, and spreading the word. It reached out via a lobby slide show, posters, flyers, pamphlets, social media, and other sources. (The department offered information in nine different languages: English, Spanish, Russian, Vietnamese, Chinese, Somali, Oromo, Amharic, and Tigrinya. The languages chosen were those most frequently requested within the patient population and/or serve patients who would benefit greatly from having such written resources about virtual visits.)

As part of its equity approach, MCHD employs community health workers to reach out to its immigrant and BIPOC communities, among others. (Credit: Twitter)

For the pilot, some virtual visits were conducted in English, with at least one visit occurring with an interpreter. Visits conducted in Spanish were with a provider who is fluent in the language, so no interpreter was needed in those cases. The health department contracts with a language service for interpreters on in-person, phone, and video calls as demand dictates.

The patient access center was also given a script to describe and promote virtual visits and guidance. The center would help determine whether telemedicine was appropriate for the patient’s needs, since some conditions required or were better suited for in-person visits. However, many were tailor-made for virtual care. Conditions that the department deemed well suited to telehealth visits included back ache; medication management; sore throat, flu, and sinus trouble; skin rash or infection; bug bites and minor burns; anxiety and depression; minor cuts and wounds; nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea; sprains and other minor injuries.

For such routine care, the advantages for patients were clear. Virtual visits were convenient (they could be done at home, on a work break, even in a parked car) and saved time and money (no childcare, fuel, parking, or public transit costs). Remote care also helped patients avoid exposure to potential illnesses such as COVID or spreading illness to someone else.

Equity in telehealth is another way in which MCHD is ensuring equity and recognition for all its BIPOC patients. Above, the health hub’s commemoration of Indigenous Peoples Day.

Of course, both patients and providers needed technical support to deal with connectivity issues and logistical problems early on. Schulman George gives kudos to Lorenzo Ortega, a nurse practitioner at the clinic, who conducted most of the telehealth visits for the pilot. His patience and persistence meeting patients remotely, despite all the obstacles thrown his way—both on the clinic end and on the patient front—was the number one reason for the pilot’s success, she says. Even in the age of technology, people power has intrinsic value: Ortega recognized the opportunity that this kind of innovation can offer and went the extra mile to make it happen.

To that point: it’s crucial to educate and train staff to have the skills, proficiency, and confidence to conduct a virtual visit and to talk it up with patients, who can sometimes get easily frustrated or disappointed if remote appointments don’t go off without a hitch (or if they are hesitant or wary to make the leap). Hiring more tech support for patients and providers is an ongoing department goal, according to Schulman George.

Telemedicine at MCHD’s student health centers was another virtual care initiative (Credit: MCHD on YouTube)

Given that this is rapidly-evolving innovation, providers also need to be prepared to pivot and learn new tools and systems. For example, since the pilot, MCHD providers have begun using Doximity Dialer to further streamline the virtual access process. A provider can initiate a call right in the patient’s electronic health record (EHR) and simply send a text link to a patient’s mobile phone, which they click on to start a visit. It does not reveal the provider’s caller ID, thus protecting their privacy. Instead, it displays the number of a health clinic, doctor’s office, or hospital that patients may be familiar with, making it more likely they will answer the call or return a missed call. The new technology integrates easily into Epic, the department’s EHR, says Schulman George, which saves time and makes video visits more efficient.

Once patients figured out how to download OCHIN MyChart and the Zoom app, they tended to prefer using that technology because it provided more information overall, says Schulman George. MyChart synchs with Epic as well. Each platform has its pros and cons (see below) and patients are given a recommendation about which one to connect on, depending on their medical condition. That said, patients get to decide which kind of appointment they sign up for. “We always go with what the patient desires,” says Schulman George. “They can override the recommendation.” After all, converting a patient to virtual visits when needed is a victory on any platform.

Lessons Learned

Replace outdated hardware

Old computers with ancient software can create unnecessary technical issues when trying to integrate new innovations such as video visits. It makes sense to keep computers current to avoid that potential complication.

Lean on tech experts for equipment recommendations

These kinds of programs depend on the right kind of technology for the job, and it’s important that a platform can be integrated with your EHR. Ask IT for advice on webcams and sound bars best suited for successful patient-provider visits. It pays to invest upfront.

Find the right people for the project

Introducing innovation requires team members who are tech savvy (or at least willing to learn), motivated, flexible, and patient. Look for staff who will stay the distance despite hurdles and curve balls.

Be open to different platforms to meet patient needs

Doximity is easy to use on a cell phone and works well with straightforward patient problems, the health department discovered. For complex, chronic health conditions, such as diabetes or heart issues, where a provider may want to reference lab reports, EHRs, or online resources, MCHD found that virtual visits via OCHIN MyChart proved the better fit.

Continue to educate patients and providers

Think beyond the pilot to ongoing efforts to train patients and staff on telehealth appointments, look to expand the service to other clinics, and keep promoting the program in multiple mediums to BIPOC patients.

___________________________________________________________________________

The Virtual Care Innovation Network is a community health collaboration founded and funded by Kaiser Permanente in partnership with CCI, National Health Care for the Homeless Council, the primary care associations in each of the nine states in which Kaiser Permanente provides care, and regional associations in California. Its goal is to design or redesign virtual care models so they continue after the pandemic abates and beyond. VCIN seeks to solve some of the complex challenges associated with the implementation, improvement, and sustainability of virtual care, also commonly known as telehealth or telemedicine.

Find this useful or interesting? We’re constantly sharing stuff like this. Sign up to receive our newsletter to stay in the loop.