What do yoga, volleyball, and a traditional Indigenous coming of age ceremony known as a Flower Dance have to do with overturning intimate partner violence?

For starters, each activity focuses on building healthy relationships, trust, and empowerment and practicing self-care and wellness. At two of its spring workshops and a 2022 summer sports camp it ran as part of Amplify Healing Connections -- which seeks to strengthen resilience to prevent domestic and intimate partner violence through positive childhood experiences -- the

McKinleyville Healthy Relationships Coalition incorporated activities that foster cultural, social, and emotional connection to encourage youth to make healthy relationship choices.

[caption id="attachment_29391" align="alignleft" width="398"]

Flower Dance demonstrations (Credit: Native Women's Collective/Facebook)

Flower Dance demonstrations (Credit: Native Women's Collective/Facebook)[/caption]

McKinleyville Healthy Relationships Coalition is a partnership between the

McKinleyville Family Resource Center, the

Native Women’s Collective, and

Open Door Community Health Centers, along with the

Food Sovereignty Lab at Cal Poly Humboldt,

Native Strength Revolution, which offers yoga and other wellness programs to Indigenous people, and

Project Rebound, a Cal Poly Humboldt program for formerly incarcerated students and those impacted by the system. For Amplify, the coalition decided to direct their efforts to its program involving Indigenous girls, young women, and femmes.

McKinleyville is a small, rural town on California’s far North Coast in Humboldt County, about five miles north of Arcata. What is now known as McKinleyville is unceded ancestral territory and the current homeland of the Wiyot Tribe, with some overlap with the Yurok Tribe. In the Wiyot language, the region is known by several names, since there were many small villages in the area, according to the McKinleyville Alliance for Racial Equity's Baseline Racial Equity Report of 2020-2021. The report notes that most Indigenous people in the region were killed, kidnapped or driven from their homeland by white settlers, starting in the 1850s, and documents the racism and discrimination against them and other people of color in the community, both historic and ongoing. One resident commented that "Many who are working to reduce racism in McKinleyville believe that focusing on eliminating the experience of racism for youth is a top priority." Said another: “We do need allies to have a safe conversation, so we can all make improvements together.”

[caption id="attachment_29389" align="alignright" width="319"]

Tall Trees Grove in McKinleyville, CA (Shutterstock)

Tall Trees Grove in McKinleyville, CA (Shutterstock)[/caption]

Aristea Saulsbury is the prevention programming and community outreach project manager at

McKinleyville Family Resource Center, a nonprofit organization designed to support, enrich, and sustain community life in this Redwood Coast enclave. In addition to her professional capacity in this partnership, Saulsbury is reconnecting with her Indigenous roots and raising a 7th grade girl, who participated in the workshops and three-day sports camp. “It’s been really cool to bridge these work relationships while continuing on my own reconnection journey and getting to be my whole self at work,” says Saulsbury. “We faced a lot of obstacles, but we kept the focus on the youth; it was so worth it.” She has a solid relationship with team partner Marlene’ Dusek, of the Native Women’s Collective, which helped navigate the hardships. “We were able to roll with the challenges and even laugh at them and keep going. It’s risky mixing the personal and the professional but in a remote community it’s essential.” Says Dusek: “Focusing on joy is critical. Joy is a radical act.”

Combining culture and healthy competition

The goals of the coalition’s workshops and volleyball camp were wide ranging. They sought to promote and embody healthy relationships, be it with a participant’s own body, movement, and exercise, or connections with the land, community, ceremony, Indigenous languages, and culture.

The series was initially conceived as four workshops leading up to a three-day volleyball camp. The coalition scaled the workshops back due to the pandemic and budget constraints. Things shifted, Saulsbury said, from what she dubs the traditional power dynamic model when collaborating with nonprofits to organize an event – something that often consists of a loop between participants and organizers (survey, feedback, revisions, implementation). Instead, the coalition tried an alternative approach: “Here’s what we can offer. What would you like to do?”

The Native Women’s Collective had previously run a volleyball camp, and youth were keen to do it again. The first workshop, with approximately 50 participants including about 25 youth, was an online yoga workshop facilitated by Native Strength Revolution, an organization with roots in Arizona and Alabama that hosts wellness classes for Indigenous peoples. COVID-19 forced the workshop online, so organizers dropped off wellness kits to youth participants’ doors. These included yoga mats, water bottles, native snacks, herbal tea, and other goodies. The care package served to create some excitement ahead of the event.

There were some silver linings to being forced online: More people could participate, and youth reported being joined by other family members interested in doing yoga. And the online workshop was enjoyed by Indigenous youth from a wider geographic area. The recording of the session has also proven a useful in-house resource to share with other youth. Finally, some shy participants were encouraged to keep their cameras off, if that made them more comfortable participating.

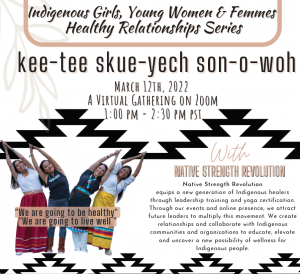

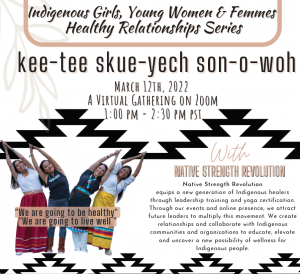

From Native Strength Revolution (Credit: Facebook)

From Native Strength Revolution (Credit: Facebook)

The McKinleyville crew proved adept at making lemonade out of lemons during this challenging time. Yoga and meditation, says Dusek, felt like a gentle but effective place to start exercising during the pandemic before moving on to the more vigorous volleyball camp. Similarly, Saulsbury notes that the yoga workshop was a way of acknowledging the stress of the pandemic and other outside factors that can get in the way of taking care of ourselves. The host organization also made available a free app for indigenous youth who wanted to continue with a yoga regimen.

Period positivity and a coming of age ritual

The second workshop, which was held in person, focused on period positivity and showcased the cultural coming of age process known as a Flower Dance, in addition to health information about menstruation. It featured free period products—pads, liners, and tampons, which were supplied by Open Door Community Health Centers, along with instructions on using reusable menstrual cups.

Saulsbury says that

Malia Honda, a primary care provider and Open Doors director with a long family history with the local Indigenous community and a deep commitment to healthcare and cultural equity work, provided information and answered questions. Participants were encouraged to send their questions anonymously via an app, another example of meeting youth where they’re most comfortable. During the workshop there was a screening of an on-point documentary that won best short documentary at the Sundance Film Festival,

Long Line of Ladies, recently featured in the New York Times. The short film profiles a teen from McKinleyville anticipating her Flower Dance, who was on hand at the workshop to field questions from her peers.

https://youtu.be/NlIMKjb_w8s

The Indigenous-made movie focuses on a coming of age ceremony for Ahty Allen and her family, who are members of the Karuk tribe. The film profiles a teen who anticipates her "Ihuk" or Flower Dance -- a ceremony that takes place after a young woman has her first menstrual cycle. According to the documentary, the ritual was practiced by the tribe for generations before the California Gold Rush, during which Native American girls and women became victims of sexual violence. The practice became dormant for over 120 years until its revival in the 1990s by a group of Karuk people.

The filmmakers spent more than four months with the tribe, family, and featured youth, before shooting the film over the course of a week. Out of respect, the documentary focuses on the lead-up to the event—a warm welcome into womanhood by her community—but intentionally doesn’t film the ceremony. After fasting, a young woman is blindfolded on a journey through the woods for four days, then emerges to perform a dance that signifies her entrance into womanhood. The film follows Ahty as she prepares for the big day – trying on a special ceremonial skirt, chatting with others about what it means to take the leap. In one scene, she practices being blindfolded with a “taáv”, a veil-like covering made of laurel feathers, while members of her community teach her the traditional dance steps that accompany this rite of passage.

Saulsbury notes that the youth who participated in this workshop were full of questions about the ritual, and some will pursue that path themselves in the future. Adult participants shared feelings of sadness about not having had the opportunity to participate when they were young. The intergenerational discussion proved productive and poignant.

Bonding over volleyball

The summer volleyball camp was about a lot more than sports and spiking a ball over a net, though there was plenty of coaching, skill development, and strength training. The benefits of working together, even if you don’t come from the same community, navigating through interpersonal issues, having the opportunity to be mentored, getting feedback, and trying different things were all part of the three-day camp held on a college campus. It was also a safe space, says Saulsbury, for the participants to explore competition and a socially sanctioned outlet for anger and aggression. Some participants, for instance, were dealing with the stress of their families facing evacuations due to rapidly encroaching wildfires at the time.

It was also a chance to connect with community. The event featured native-made food from local caterers, acorn prep instructions, and a traditional salmon fish pit. Surplus salmon went to Project Rebound members who took the extra fish dinners to juvenile hall, where they were eagerly received. Some also went to families displaced by wildfires in the area. The opportunities to consider community beyond the camp emerged organically. “That was an unexpected connection and benefit,” says Saulsbury. There were also opportunities to learn words in Indigenous languages and discover other other aspects of Indigenous culture in an authentic way.

The health center partner provided COVID rapid tests and support after what turned out to be false positive results during the camp -- just another hiccup along the way. Thirty youth signed up for the camp, which drew from a vast geographic reach, courtesy of word of mouth. Some families drove three hours to have their daughter attend; some even flew in from the Southwest. “We were able to show up for each other during the camp and demonstrate what community is all about,” says Saulsbury, who notes there were organizational difficulties happening behind the scenes that the participants weren’t aware of and were intentionally shielded from. “We’ve all been through so many traumatic events—relationship issues, racism, violence, wildfires, the pandemic. We were able to model what it looks like to support each other through tough times.”

Lessons Learned

Take existing resources and bolster them

Combine the skills and talents of individual teams to create a thriving partnership that doesn’t duplicate what’s already in place and breaks down silos. Operate from a strengths-based platform and build from there.

Make engagement easy

It’s important to eliminate barriers to access for youth programming. In rural communities, such as McKinleyville, that can mean providing transport so teens can get to an activity, explains Saulsbury. Similarly, be prepared to tackle the less-desirable logistical matters—securing spaces, producing materials, planning itineraries—so participants can focus on the fun, cultural, physical, and social programmatic aspects and activities.

Embrace intergenerational learning

During the workshops and camp, youth enjoyed engaging with, learning from, and hearing stories from big sisters, moms, and aunts in the community. Likewise, adult women expressed gratitude about witnessing and learning about local Indigenous culture, such as the Flower Dance, that wasn’t available to them in their youth.

Be aware that planning events requires people power

To avoid stress, burnout, and overwhelm, make sure you have enough people in place to help make events a reality. It usually takes more hands, hearts, and minds than you think you’ll need, say these organizers. Enlist as much assistance as you can get and delegate as needed.

Nurture relationships

Connection is especially important in rural communities, says Saulsbury, when there is often overlap in professional and personal relationships and stakeholders hold roles in multiple spaces, which can prove challenging. That said, sustaining relationships is essential in remote regions and demands attention and TLC.

Give grace to team members when life happens

Commit to working in ways that fit with the needs of each partner and the individuals within those partnerships. Focus on kindness, respect, and compassion in the face of personal obstacles, unexpected roadblocks, and other hurdles.

__________________________________________________________________________

Amplify Healing Connections seeks to strengthen interventions designed to prevent domestic violence and promote health and well-being for adolescent youth and their adult allies. Launched in March 2021, the 22-month program, with funding from the Blue Shield of California Foundation, is a collaboration with six California-based, multi-sector partnerships, each involving at least one community-based organization and one health care provider serving youth 12-18 years old. Youth-service organizations play a pivotal role in promoting healthy communication and providing a strong, nourishing environment for young people and their caregivers. Coordinated efforts across community organizations can amplify positive childhood experiences (PCEs) and help prevent, reduce, and even reverse the impact of early adversity.

Stories in this series:

Flower Dance demonstrations (Credit: Native Women's Collective/Facebook)[/caption]

McKinleyville Healthy Relationships Coalition is a partnership between the McKinleyville Family Resource Center, the Native Women’s Collective, and Open Door Community Health Centers, along with the Food Sovereignty Lab at Cal Poly Humboldt, Native Strength Revolution, which offers yoga and other wellness programs to Indigenous people, and Project Rebound, a Cal Poly Humboldt program for formerly incarcerated students and those impacted by the system. For Amplify, the coalition decided to direct their efforts to its program involving Indigenous girls, young women, and femmes.

McKinleyville is a small, rural town on California’s far North Coast in Humboldt County, about five miles north of Arcata. What is now known as McKinleyville is unceded ancestral territory and the current homeland of the Wiyot Tribe, with some overlap with the Yurok Tribe. In the Wiyot language, the region is known by several names, since there were many small villages in the area, according to the McKinleyville Alliance for Racial Equity's Baseline Racial Equity Report of 2020-2021. The report notes that most Indigenous people in the region were killed, kidnapped or driven from their homeland by white settlers, starting in the 1850s, and documents the racism and discrimination against them and other people of color in the community, both historic and ongoing. One resident commented that "Many who are working to reduce racism in McKinleyville believe that focusing on eliminating the experience of racism for youth is a top priority." Said another: “We do need allies to have a safe conversation, so we can all make improvements together.”

[caption id="attachment_29389" align="alignright" width="319"]

Flower Dance demonstrations (Credit: Native Women's Collective/Facebook)[/caption]

McKinleyville Healthy Relationships Coalition is a partnership between the McKinleyville Family Resource Center, the Native Women’s Collective, and Open Door Community Health Centers, along with the Food Sovereignty Lab at Cal Poly Humboldt, Native Strength Revolution, which offers yoga and other wellness programs to Indigenous people, and Project Rebound, a Cal Poly Humboldt program for formerly incarcerated students and those impacted by the system. For Amplify, the coalition decided to direct their efforts to its program involving Indigenous girls, young women, and femmes.

McKinleyville is a small, rural town on California’s far North Coast in Humboldt County, about five miles north of Arcata. What is now known as McKinleyville is unceded ancestral territory and the current homeland of the Wiyot Tribe, with some overlap with the Yurok Tribe. In the Wiyot language, the region is known by several names, since there were many small villages in the area, according to the McKinleyville Alliance for Racial Equity's Baseline Racial Equity Report of 2020-2021. The report notes that most Indigenous people in the region were killed, kidnapped or driven from their homeland by white settlers, starting in the 1850s, and documents the racism and discrimination against them and other people of color in the community, both historic and ongoing. One resident commented that "Many who are working to reduce racism in McKinleyville believe that focusing on eliminating the experience of racism for youth is a top priority." Said another: “We do need allies to have a safe conversation, so we can all make improvements together.”

[caption id="attachment_29389" align="alignright" width="319"] Tall Trees Grove in McKinleyville, CA (Shutterstock)[/caption]

Aristea Saulsbury is the prevention programming and community outreach project manager at McKinleyville Family Resource Center, a nonprofit organization designed to support, enrich, and sustain community life in this Redwood Coast enclave. In addition to her professional capacity in this partnership, Saulsbury is reconnecting with her Indigenous roots and raising a 7th grade girl, who participated in the workshops and three-day sports camp. “It’s been really cool to bridge these work relationships while continuing on my own reconnection journey and getting to be my whole self at work,” says Saulsbury. “We faced a lot of obstacles, but we kept the focus on the youth; it was so worth it.” She has a solid relationship with team partner Marlene’ Dusek, of the Native Women’s Collective, which helped navigate the hardships. “We were able to roll with the challenges and even laugh at them and keep going. It’s risky mixing the personal and the professional but in a remote community it’s essential.” Says Dusek: “Focusing on joy is critical. Joy is a radical act.”

Tall Trees Grove in McKinleyville, CA (Shutterstock)[/caption]

Aristea Saulsbury is the prevention programming and community outreach project manager at McKinleyville Family Resource Center, a nonprofit organization designed to support, enrich, and sustain community life in this Redwood Coast enclave. In addition to her professional capacity in this partnership, Saulsbury is reconnecting with her Indigenous roots and raising a 7th grade girl, who participated in the workshops and three-day sports camp. “It’s been really cool to bridge these work relationships while continuing on my own reconnection journey and getting to be my whole self at work,” says Saulsbury. “We faced a lot of obstacles, but we kept the focus on the youth; it was so worth it.” She has a solid relationship with team partner Marlene’ Dusek, of the Native Women’s Collective, which helped navigate the hardships. “We were able to roll with the challenges and even laugh at them and keep going. It’s risky mixing the personal and the professional but in a remote community it’s essential.” Says Dusek: “Focusing on joy is critical. Joy is a radical act.”

The series was initially conceived as four workshops leading up to a three-day volleyball camp. The coalition scaled the workshops back due to the pandemic and budget constraints. Things shifted, Saulsbury said, from what she dubs the traditional power dynamic model when collaborating with nonprofits to organize an event – something that often consists of a loop between participants and organizers (survey, feedback, revisions, implementation). Instead, the coalition tried an alternative approach: “Here’s what we can offer. What would you like to do?”

The Native Women’s Collective had previously run a volleyball camp, and youth were keen to do it again. The first workshop, with approximately 50 participants including about 25 youth, was an online yoga workshop facilitated by Native Strength Revolution, an organization with roots in Arizona and Alabama that hosts wellness classes for Indigenous peoples. COVID-19 forced the workshop online, so organizers dropped off wellness kits to youth participants’ doors. These included yoga mats, water bottles, native snacks, herbal tea, and other goodies. The care package served to create some excitement ahead of the event.

There were some silver linings to being forced online: More people could participate, and youth reported being joined by other family members interested in doing yoga. And the online workshop was enjoyed by Indigenous youth from a wider geographic area. The recording of the session has also proven a useful in-house resource to share with other youth. Finally, some shy participants were encouraged to keep their cameras off, if that made them more comfortable participating.

The series was initially conceived as four workshops leading up to a three-day volleyball camp. The coalition scaled the workshops back due to the pandemic and budget constraints. Things shifted, Saulsbury said, from what she dubs the traditional power dynamic model when collaborating with nonprofits to organize an event – something that often consists of a loop between participants and organizers (survey, feedback, revisions, implementation). Instead, the coalition tried an alternative approach: “Here’s what we can offer. What would you like to do?”

The Native Women’s Collective had previously run a volleyball camp, and youth were keen to do it again. The first workshop, with approximately 50 participants including about 25 youth, was an online yoga workshop facilitated by Native Strength Revolution, an organization with roots in Arizona and Alabama that hosts wellness classes for Indigenous peoples. COVID-19 forced the workshop online, so organizers dropped off wellness kits to youth participants’ doors. These included yoga mats, water bottles, native snacks, herbal tea, and other goodies. The care package served to create some excitement ahead of the event.

There were some silver linings to being forced online: More people could participate, and youth reported being joined by other family members interested in doing yoga. And the online workshop was enjoyed by Indigenous youth from a wider geographic area. The recording of the session has also proven a useful in-house resource to share with other youth. Finally, some shy participants were encouraged to keep their cameras off, if that made them more comfortable participating.

From Native Strength Revolution (Credit: Facebook)

The McKinleyville crew proved adept at making lemonade out of lemons during this challenging time. Yoga and meditation, says Dusek, felt like a gentle but effective place to start exercising during the pandemic before moving on to the more vigorous volleyball camp. Similarly, Saulsbury notes that the yoga workshop was a way of acknowledging the stress of the pandemic and other outside factors that can get in the way of taking care of ourselves. The host organization also made available a free app for indigenous youth who wanted to continue with a yoga regimen.

From Native Strength Revolution (Credit: Facebook)

The McKinleyville crew proved adept at making lemonade out of lemons during this challenging time. Yoga and meditation, says Dusek, felt like a gentle but effective place to start exercising during the pandemic before moving on to the more vigorous volleyball camp. Similarly, Saulsbury notes that the yoga workshop was a way of acknowledging the stress of the pandemic and other outside factors that can get in the way of taking care of ourselves. The host organization also made available a free app for indigenous youth who wanted to continue with a yoga regimen.