The way pediatrician Maggie Gilbreth tells it, she wrote her grant proposal to the Resilient Beginnings Network over a holiday weekend in 2020 as a way to work through frustrations with the healthcare system. “I really just felt something was very broken with how we were treating each other and interacting as a team,” says Gilbreth, who takes care of pediatric patients at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital (ZSFGH). “For me it was really about workplace culture and community. If we can’t treat each other with more compassion and respect, how can we bring those values to our patients and families?”

After the grant proposal was accepted, the Children’s Health Center team, based at the ZSFGH and Trauma Center, joined RBN. Since that time, the team has made major strides in practicing healing and trauma-informed care both with patients and among team members. Children’s Health Center is thinking big: It envisions becoming a healing organization with a trauma-and-resilience based care model for patients and care team members. But the center doesn’t screen for ACEs (adverse childhood experiences), Gilbreth says, because the team simply assumes that the ACEs burden of its patients and caregivers is high. (Based on a 2018 clinic pilot study, most CHC patient caregivers have at least one adverse childhood experience, and almost half have experienced four or more ACEs.) Instead, the organization has focused resources on interventions to buffer toxic stress, which is linked to ACEs and other forms of trauma.

Still, addressing ACEs informs everything the center does. “We really do have many elements of a trauma-informed clinical environment that affects not only our patients but also our team members,” notes Gilbreth, who points to several such initiatives. One is a project led by pediatrician Danielle McBride and social worker Katherine Hallinan, in which they helped design cloud-based and electronic health record-integrated tools and workflows that make it easier to link young patients to developmental services at San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD).

Maggie Gilbreth, MD

The project embodies this RBN team’s maxim that those closest to the problem are closest to the solution. The ideas originated from parents who participated in a clinic-wide 2020-21 journey-mapping exercise, where they talked about the difficulty they had navigating the school district, which often created insurmountable barriers, they said, to the services they urgently needed. By incorporating what they learned by listening to parents, McBride and Hallinan were able to create improvements at a systems level.

The health center has successfully helped dozens of parents by educating providers and creating a toolkit that includes explanations of procedures, pre-filled forms, suggested language on discussion points, and ways to support parents as they complete each step in the complex process of accessing testing and connecting to developmental resources and other services. “There’s been such positive feedback about the SFUSD toolkit,” says Gilbreth. “Now all the clinics in the San Francisco Health Network have access to this tool. It’s been really appreciated; there’s an acknowledgement of just how difficult it is to get kids the services they deserve.”

This kind of success does not come easy, Gilbreth notes. “The system is not designed to center patient and family voices,” says the RBN team lead, who is a certified Spanish-English bilingual provider. “I really want to applaud Katherine and Danielle for [wanting] their RBN time to be focused on elevating patient voices and how we think about the work we do.” It takes more time and effort, she says, and isn’t the typical structure, but it is an intentional approach to re-center patients and families.

Programs designed to help high-risk families

The health clinic has multiple touchpoints for high-risk families. It is a HealthySteps site, which means the caregivers of patients from birth through age five can get additional support to help their family thrive. The HealthySteps team, where Hallinan is a lead clinician, addresses parenting questions, connecting with community partners and assisting parents with their own mental health needs. CHC also has on-site behavioral health clinicians who can address mild-to-moderate mental health needs of patients six years and older.

In addition, primary care patients of all ages at CHC can be connected to the Health Advocates team, whose role includes linking families with community programs that assist with basic needs such as food, housing, employment, and financial assistance. Health advocates check in with families after a visit via phone to ensure connections to resources are made.

And the center is also home to the Bridges Clinic, which offers support to the families of patients transitioning to a new place and culture. The Bridges Clinic includes a family navigation program, co-led by family resource navigator Maite Garcia, who like Hallinan and McBride, is part of the RBN team. Bridges navigators, which include bilingual and bicultural team members, support services to help newcomers make a home in San Francisco regardless of insurance or documentation status. Family navigators help to connect recent refugees and new immigrants with dental care, mental health care, legal services, and other community resources.

Gilbreth describes Garcia’s group as the gold standard for social determinants of health (SDOH) screening and resource connection. Gilbreth adds that the clinic is fortunate to have several teams and care members that contribute to SDOH screening and resource connection, including Health Advocates, a behavioral assistant, and navigation services for patients with severe mental health needs. As part of RBN, Garcia has brought these groups together to discuss issues and learn together. Garcia is delighted to share what she knows but she doesn’t impose her vision on other groups, says Gilbreth. She’s a natural connector who brings people together, including community experts, to address challenges that navigators and families face. Prior to this approach, groups were working in their own silos, sometimes for the same patients.

There is, of course, an economy of scale to collaborating together. Now the leads of different programs try to coordinate and communicate to avoid duplication of services or outreach. And sharing successful strategies and external resources is becoming more routine.

The work done by the RBN team at the Children’s Health Center augments other trauma care at the San Francisco hospital.

The Children’s Health Center – a San Francisco Health Network clinic – serves a low-income, BIPOC community in an area of the city with a history of redlining. Sixty to 70 percent of patients identify as Latinx; about 10% identify as Black. The clinic has around 30,000 visits a year, with 10,000 unique patient visits and 8,000 primary care patients. Team members are bicultural and bilingual, speaking English, Spanish, Cantonese, Mandarin, Vietnamese, and Thai; interpreters are available for patients who speak other languages. The center’s RBN team also includes Dominique Nash, the clinic’s eligibility supervisor and clinic leadership team representative, and Amanda Rodriguez, a consultant with expertise in trauma-informed care training and systems change.

Managing and supervising the RBN team has provided an opportunity to learn new leadership skills, notes Gilbreth. A transactional approach that focuses only on deliverables by a certain date, for example, isn’t trauma-informed, she says. “Every person on our team is valued and has unique interests, skills, and expertise,” explains Gilbreth. “I tend to give people a lot of space.” She favors a slow and steady pace versus one that is pressured. ‘I want it to feel like it’s happening in a way that works for people,” she says. ‘There is never enough time. I wish I had 20 hours a week to do RBN work, that would be great. But I don’t. At least, it doesn’t feel like COVID is sucking all the air out of the room anymore — it feels like there is space and time to have new conversations and move initiatives forward.”

A trauma-informed practice supports employees, too

Children’s Health Center’s RBN team has buy-in from the top. Leadership gave the go-ahead to close clinic for one hour a month for an “all hands gathering” to support trauma-informed and resilience-based practices. “There has been an explosion of support for RBN work and ideas generated across the leadership team and within the RBN team,” says Gilbreth.

In the beginning, the meetings were in a lecture hall and had an educational focus, with videos about trauma-informed care. With feedback from staff, the meetings have evolved into group activities, held in a meeting room with food and coffee in the mix. “It hasn’t happened yet but maybe one day it will involve a nap,” she half-jokingly adds, of a group activity that focuses on reflection. “We never paused before, ever. I feel like we’re learning how to build new habits. No one ever taught me to stop and pause and listen and not be reactive with people. So for me personally, it’s been a huge area of growth.”

At the center’s gathering, eligibility, nursing, providers, specialists, and behavioral health staff all come together at the same time, rather than holding separate meetings. “This is so not rocket science but it is so awesome,” says Gilbreth. Out of one gathering came the suggestion to create a clinic community board that can help staff feel connected and relieve stress. The board includes everything from staff and pet photos to resource links, inspirational quotes, and recipes.

It’s a collective learning experience, she says, with the hope that the team is building a foundation of rapport and trust, which can help make it easier to have the tough conversations around what to do when something escalates in clinic. As one example, Gilbreth points to a team discussion that helped a relatively new provider handle a challenging situation that involved contacting Child Protective Services (CPS) and concerns around equity with regard to the clinic’s CPS referrals.

“We have a whole program we’re piloting around high-risk consultation and trying to provide balance and another way forward that’s not typically suggested for a lot of these cases,” she says of an issue that hadn’t been on her radar but bubbled up organically from this experience. “Now we have a nurse, behavioral health worker, and a provider meet and talk about difficult cases and offer support to team members who are feeling scared about what to do beyond what they’ve been told in training, which is: ‘You could lose your license if you don’t call CPS.’”

Even when everyone agrees contacting CPS is the right call, they assist providers on how to present a case and discuss the kind of outcome they are looking for, which is unique to each family. Difficult decisions made in isolation and based on fear are often not the best decisions, adds Gilbreth, who notes they don’t always have the intended impact or best serve children or families. “There are layers of potential trauma here—for the child, the parent, and the health care team,” she says. “We’re trying to intentionally and thoughtfully address it all.”

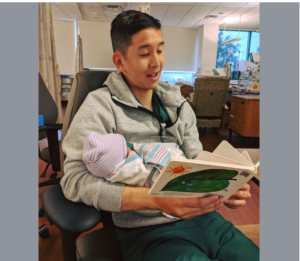

RBN builds on previous work done by the Children’s Health Center, including a pilot program training parents to read to their babies, which is shown to improve early language and brain development. Credit: ZSFGH Twitter

In October 2022, the Children’s Health Center also held an all-clinic, all-day RBN retreat, staffing the clinic with minimal coverage on the day so as many people as possible could attend. The off-site retreat, designed with the clinic’s core values in mind included Ayesha McAdams-Mahmoud, a national expert on storytelling, to help facilitate connective activities and group reflection. Since October, many in clinic have commented on how important it was to get to know each other better, and to work collaboratively on problems as they come up. The retreat was a great jumping off point to continue to build on the center’ four main operating principles: reflection, connection, celebration, and restoration.

CHC’s RBN team has other goals. It is exploring how it can provide more culturally consistent care, especially for black patients. CHC pediatrician McBride is partnering with others on the ZSFGH campus to envision a model for black-centered pediatric care, in part to close the health equity gap (given disparities between well child visits and vaccinations for Black children as compared with White children). Such a model, which would be in partnership with other programs within the larger health system, is a ways down the track. As a first step, McBride and Hallinan are conducting a listening tour with Black families who come to CHC for care, to generate ideas, learn, and understand where the organization currently falls short.

Gilbreth sees herself as something of a misfit in healthcare. But she is clear that cultural change within large institutions and systems—weeding out racism and sexism, incorporating patient voices, and addressing the trauma and resilience of patients and staff alike—requires innovative thinking and change. “Systems produce outcomes that they are designed to produce, and the system now perpetuates unequal health outcomes,” she says. “We think by doubling down on our current system rather than radically re-envisioning how we provide care that we’re going to make a difference. I think we actually need to radically re-envision ourselves.”

Gilbreth is optimistic that real change is possible –”we have so much momentum right now” – but she is also realistic: “I’m really not sure what parts of what we have been doing will sustain beyond the grant cycle. Maybe that’s fine. Maybe some of the most impactful pieces will continue. I do worry. I feel like we’re building and building and then it might all fall at the last moment, which feels not trauma informed to me to pull it out from under people. There are never enough resources to meet demand –maybe that’s not the point. Maybe changing the environment in which you deliver the services you can deliver is the point.” Or put another way, as a mentor once, told her: Maybe it’s not so much about what you do, but how you show up to do the work.

Still, as Gilbreth notes, there is good, strong research to support the value of “treating” trauma—just like a pediatrician would follow the current science when it comes to treating a child with, say, an ear infection. Why should caring for patients and their families who have experienced trauma be any different from tackling a routine case of otitis media?

Lessons Learned

Find out what your organization is already doing well and make it better. There’s no need to reinvent the wheel or fix what isn’t broken. Acknowledge the good work that has already been done and build on it to incorporate a trauma-informed approach.

Cultivate connection. COVID has taken a toll. The transition to remote work and telehealth appointments has come with a cost: Perhaps the biggest loss has been that communication within teams and organizations has taken a hit. Look for ways to connect, such as Children’s Health Center’s all-staff trauma-informed care gathering. The pandemic has highlighted the need to be more intentional about focusing on staff communication. CHC started with a 2- to 5- minute pause for reflection in their regular monthly meetings and grew from there.

Look for ways to collaborate. Sometimes different team members may be working on the same issue for a patient and their families without realizing it. Find ways to work together to avoid replicating services or feeling disjointed in terms of offering care. Avoid operating in silos.

Include and elevate patient voices. Don’t assume that an organization knows what’s best for the community members it serves. Ask patients and their families how you might best meet their needs. Hold listening sessions. Journey map with patient families. Say “yes” to as many of the communities requests as you can reasonably accommodate in terms of providing care. Remember: The people who are closest to the problem are also likely closest to the solutions.

Prioritize racially and culturally consistent care. Families want to see faces like their own when they seek medical care. And they want to be able to speak in their preferred language with their health care team. Hiring should prioritize staffing and leadership to reflect the demographics of the residents that a health center serves.

Think beyond grant programs and create a longer runway for funding. As part of leadership buy-in, prioritizing culture change and figuring out ways to sustain these changes needs to be addressed from the start. Even a small amount of change can be meaningful and might be all that is possible with existing resources. Don’t let wanting to do it all paralyze an organization or team from starting to bring about change.

Children’s Health Center is part of the Resilient Beginnings Network, a learning program that promotes trauma- and resilience-informed care so that 100,000 young children and their caregivers in the San Francisco Bay Area have the support they need to be well and thrive. The Resilient Beginnings Network is powered by the Center for Care Innovations, an Oakland-based nonprofit that fosters health equity and innovation in the health care safety net, and by Genentech Charitable Giving.

Find this useful or interesting? We’re constantly sharing stuff like this. Sign up to receive our newsletter to stay in the loop.