West County Health provider welcoming baby to the exam room (WCHC)[/caption]

West County Health provider welcoming baby to the exam room (WCHC)[/caption]

Dr. Ellen Bauer remembers her feeling of exhilaration when she first imagined the idea for Project 100.

The former public health director of Sonoma County, Bauer joined West County Health Centers in 2020 as its chief administrative officer. Concerned about the problems that the clinic’s low-income families faced, she was interested in taking a public health approach to give the 100 or so babies born each year in the lower Russian River area – one of the poorest parts of the county -- their best chance at a healthy and joyful life. The name Project 100 spoke to her, she said, because it seemed like a concrete way to keep a laser focus on prevention and healthy early development for those 100 babies -- one of the most effective ways to transform the long-term health of a community Bauer had experience organizing community health care coalitions, working with childhood trauma expert Robert Anda and others to train more than 60 people in Sonoma County to do outreach about adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) such as neglect and abuse and the toxic stress such experiences can create, which research links to depression, diabetes, heart disease, substance use and other serious health problems. “Dr. Anda talked about it being the public health discovery of our generation,” said Bauer. “And in West County, it is a huge opportunity.” [caption id="attachment_30907" align="aligncenter" width="567"] Project 100 members looking at the systems mapping project (Dr. Ellen Bauer on far right)[/caption]

The project seeks "to level the playing field for all babies in the area,” Bauer said. “When I came to West County Health Centers, I wanted to continue my work with community partnerships, to focus on prevention and work ‘upstream’ to create healthy environments for babies and children in the lower Russian River area.”

“Upstream,” in this case, meant involving the lower Russian River community in a Self-Healing Communities model, often described as one in which a culture of illness turns from conflict and despair into a culture of healing by involving community members as agents of change. The question for the community in Project 100 was, what did those 100 babies need to live their best lives?

“We thought this is something that is incredibly important but small enough that we can wrap our arms around it,” said Bauer.

Jason Cunningham, the chief executive officer of West County Health Centers, agrees. He has worked there for more than 20 years and has served as the health center’s CEO since early 2020, although he also continues to see patients as a physician (“it’s always my favorite part of the job”). In Project 100, Cunningham is excited to use the design thinking tools he and other WCHC staff learned in programs with the Center for Care Innovations, he says, to help make equity a reality in an area suffering from generational poverty, lack of jobs, addiction, untreated mental illness and homelessness.

Project 100 members looking at the systems mapping project (Dr. Ellen Bauer on far right)[/caption]

The project seeks "to level the playing field for all babies in the area,” Bauer said. “When I came to West County Health Centers, I wanted to continue my work with community partnerships, to focus on prevention and work ‘upstream’ to create healthy environments for babies and children in the lower Russian River area.”

“Upstream,” in this case, meant involving the lower Russian River community in a Self-Healing Communities model, often described as one in which a culture of illness turns from conflict and despair into a culture of healing by involving community members as agents of change. The question for the community in Project 100 was, what did those 100 babies need to live their best lives?

“We thought this is something that is incredibly important but small enough that we can wrap our arms around it,” said Bauer.

Jason Cunningham, the chief executive officer of West County Health Centers, agrees. He has worked there for more than 20 years and has served as the health center’s CEO since early 2020, although he also continues to see patients as a physician (“it’s always my favorite part of the job”). In Project 100, Cunningham is excited to use the design thinking tools he and other WCHC staff learned in programs with the Center for Care Innovations, he says, to help make equity a reality in an area suffering from generational poverty, lack of jobs, addiction, untreated mental illness and homelessness.

“The design thinking we received through those CCI programs really set the stage for Project 100,” he said. “We feel like community health centers are uniquely positioned to help solve some of the wicked problems – the seemingly intractable problems – that are plaguing this area. But we have to work collaboratively with the community, because we can only do this together. We want to use human-centered design and systems thinking to help us learn and tap into community wisdom.”

The three convening organizations in Project 100 -- West County Health Centers, River to Coast Children’s Services, and the Guerneville School District -- assembled "an amazing group" of parents, grandparents, caregivers, nonprofit employees, educators, health care workers, addiction specialists, health care workers, and government and business leaders to work on the project, Cunningham said. The Spanish-speaking community in the lower Russian River area has also been very involved with Project 100's systems mapping project, reporting that isolation, racism toward Latinos, fear of being deported, and lack of trust in the wider community serve as barriers to seeking help or health care. "I think that is one of the most surprising things we learned in our systems mapping -- how isolated the Latino community feels," he says.

“The design thinking we received through those CCI programs really set the stage for Project 100,” he said. “We feel like community health centers are uniquely positioned to help solve some of the wicked problems – the seemingly intractable problems – that are plaguing this area. But we have to work collaboratively with the community, because we can only do this together. We want to use human-centered design and systems thinking to help us learn and tap into community wisdom.”

The three convening organizations in Project 100 -- West County Health Centers, River to Coast Children’s Services, and the Guerneville School District -- assembled "an amazing group" of parents, grandparents, caregivers, nonprofit employees, educators, health care workers, addiction specialists, health care workers, and government and business leaders to work on the project, Cunningham said. The Spanish-speaking community in the lower Russian River area has also been very involved with Project 100's systems mapping project, reporting that isolation, racism toward Latinos, fear of being deported, and lack of trust in the wider community serve as barriers to seeking help or health care. "I think that is one of the most surprising things we learned in our systems mapping -- how isolated the Latino community feels," he says.

A Tourist Town Where Low-Income Residents Struggle to Survive

Guerneville, a small town in the heart of the lower Russian River, is a tourist hotspot for Bay Area locals and beyond. Music festivals like the Russian River Jazz and Blues series attract people from as far away as Europe and Australia to the tiny Sonoma wine country river town. But not enough tourist dollars trickle down to the area’s low-income residents to offset the steep rise in housing and rental prices ushered in by AirBnbs renting for upwards of $369 a night or upscale ranches with “rustic chic” cabins, organic meals and wine tastings for up to $653 dollars a night. [caption id="attachment_30912" align="aligncenter" width="581"] Robert Cray performs at the Russian River Blues Festival in Guerneville on June 10, 2018. (Credit: Sterling Munksgard)[/caption]

Seeking affordable housing, many low-income people in Sonoma County moved to the lower Russian River, one of the more remote parts of the county. Unfortunately, they found themselves buffeted by soaring rental prices and by climate change. The neighboring census tracts of Guerneville, Forestville, and Monte Rio show the highest poverty rates in Sonoma County (37%, 34%, and 41%, respectively, live below 200% of the federal poverty line).

The community has also weathered multiple natural disasters in recent years, Bauer said, including two wildfires in 2017 and 2020 resulting in mass evacuations and filling the air with smoke and ash. The Russian River also flooded its banks in 2017 and 2019, spilling into the downtown areas of Guerneville and Monte Rio, and causing further evacuations, property loss, job displacement, extensive damage to local schools and school closures, a catastrophe soon followed by the Covid pandemic and increased social isolation. “These layers of emotional stress have taken a toll, resulting in health challenges that our current systems are not equipped to address,” Bauer said.

A lot of low-income families who live in small former summer cabins tucked into the hills and canyons along the Russian River also face economic threats. “It’s one area in our county where people have moved for affordability,” Bauer said. “It’s one of the last bastions of slightly affordable housing, but even that's changing. There are struggles and issues with vacation rentals eating into available housing stock for residents. In addition to economic challenges, there's significant intergenerational trauma and poverty that just keeps getting passed on, along with issues of addiction and unaddressed mental health."

"The time seemed ripe to come together as a community across sectors to understand the forces affecting early childhood development and to talk about where we wanted to see change in our community," she concluded.

[caption id="attachment_30909" align="aligncenter" width="584"]

Robert Cray performs at the Russian River Blues Festival in Guerneville on June 10, 2018. (Credit: Sterling Munksgard)[/caption]

Seeking affordable housing, many low-income people in Sonoma County moved to the lower Russian River, one of the more remote parts of the county. Unfortunately, they found themselves buffeted by soaring rental prices and by climate change. The neighboring census tracts of Guerneville, Forestville, and Monte Rio show the highest poverty rates in Sonoma County (37%, 34%, and 41%, respectively, live below 200% of the federal poverty line).

The community has also weathered multiple natural disasters in recent years, Bauer said, including two wildfires in 2017 and 2020 resulting in mass evacuations and filling the air with smoke and ash. The Russian River also flooded its banks in 2017 and 2019, spilling into the downtown areas of Guerneville and Monte Rio, and causing further evacuations, property loss, job displacement, extensive damage to local schools and school closures, a catastrophe soon followed by the Covid pandemic and increased social isolation. “These layers of emotional stress have taken a toll, resulting in health challenges that our current systems are not equipped to address,” Bauer said.

A lot of low-income families who live in small former summer cabins tucked into the hills and canyons along the Russian River also face economic threats. “It’s one area in our county where people have moved for affordability,” Bauer said. “It’s one of the last bastions of slightly affordable housing, but even that's changing. There are struggles and issues with vacation rentals eating into available housing stock for residents. In addition to economic challenges, there's significant intergenerational trauma and poverty that just keeps getting passed on, along with issues of addiction and unaddressed mental health."

"The time seemed ripe to come together as a community across sectors to understand the forces affecting early childhood development and to talk about where we wanted to see change in our community," she concluded.

[caption id="attachment_30909" align="aligncenter" width="584"] Firefighters trying to stop 2020 wildfire in northern California (Shutterstock)[/caption]

The lower Russian River has already demonstrated remarkable resilience for making it through all manner of catastrophic natural disasters, Bauer added. “The community has a spirit of self-reliance and willingness to help neighbors in times of trouble. There already is a bit of, ‘Hey, bad things are happening, we don’t know when help is coming, so we need to help each other.’ It's a nice thing to build on.”

The initiative got its genesis last spring, when West County Health Centers, the nonprofit Russian River Area Resources and Advocates (RRARA, informally known as “rah-rah”), and Sonoma County Supervisor Lynda Hopkin's office held a Design Jam session to examine how the beleaguered community could help heal itself. The organization pinpointed child health as a pressing opportunity for collective action, and out of that session came plans for a new park and a new community recreation center as well as Project 100.

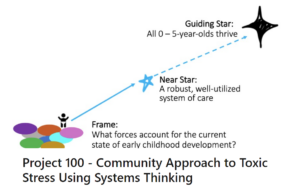

Project 100 is focused on addressing toxic stress in the area’s babies and young children, many of whom face hunger, poverty, homelessness or parental drug use. Toxic stress – severe, repeated stress that is overwhelming -- has an especially outsized effect on the long-term health of children up to age five: It can disrupt their developing brain architecture and raise the risk of stress-related disease.

Project 100’s short-term goal is to create a robust system of care that fosters each baby’s healthy early childhood development, using standard measures to track improvement. Its long-term goal is to use systems thinking to create a healthy, nurturing environment in the community in which all children can flourish.

[caption id="attachment_30906" align="aligncenter" width="603"]

Firefighters trying to stop 2020 wildfire in northern California (Shutterstock)[/caption]

The lower Russian River has already demonstrated remarkable resilience for making it through all manner of catastrophic natural disasters, Bauer added. “The community has a spirit of self-reliance and willingness to help neighbors in times of trouble. There already is a bit of, ‘Hey, bad things are happening, we don’t know when help is coming, so we need to help each other.’ It's a nice thing to build on.”

The initiative got its genesis last spring, when West County Health Centers, the nonprofit Russian River Area Resources and Advocates (RRARA, informally known as “rah-rah”), and Sonoma County Supervisor Lynda Hopkin's office held a Design Jam session to examine how the beleaguered community could help heal itself. The organization pinpointed child health as a pressing opportunity for collective action, and out of that session came plans for a new park and a new community recreation center as well as Project 100.

Project 100 is focused on addressing toxic stress in the area’s babies and young children, many of whom face hunger, poverty, homelessness or parental drug use. Toxic stress – severe, repeated stress that is overwhelming -- has an especially outsized effect on the long-term health of children up to age five: It can disrupt their developing brain architecture and raise the risk of stress-related disease.

Project 100’s short-term goal is to create a robust system of care that fosters each baby’s healthy early childhood development, using standard measures to track improvement. Its long-term goal is to use systems thinking to create a healthy, nurturing environment in the community in which all children can flourish.

[caption id="attachment_30906" align="aligncenter" width="603"] Credit: West County Health[/caption]

Systems thinking, something relatively new to many organizations but which has long been practiced by First Nations communities and other indigenous peoples, is a practice intended to help bring clarity to thorny and seemingly irremovable challenges, with a focus on helping systems heal and thrive. Tools used in systems mapping — which can include actor mapping, iceberg mapping, and forces mapping, among other things — are exercises that help people discover patterns and interconnectedness. The goal is to find sustainable pathways to move forward while being willing to adapt to more change as the system continues to evolve.

The difference in Project 100’s approach to a healthy childhood is that people often focus on why certain children are not thriving, but systems thinking "helps us shift our mindset from thinking that certain children are not thriving to thinking that the systems around children are not fostering thriving," according to Project 100 team member Alexis Wielunski, a program director at the Center for Care Innovations.

[caption id="attachment_30911" align="alignright" width="300"]

Credit: West County Health[/caption]

Systems thinking, something relatively new to many organizations but which has long been practiced by First Nations communities and other indigenous peoples, is a practice intended to help bring clarity to thorny and seemingly irremovable challenges, with a focus on helping systems heal and thrive. Tools used in systems mapping — which can include actor mapping, iceberg mapping, and forces mapping, among other things — are exercises that help people discover patterns and interconnectedness. The goal is to find sustainable pathways to move forward while being willing to adapt to more change as the system continues to evolve.

The difference in Project 100’s approach to a healthy childhood is that people often focus on why certain children are not thriving, but systems thinking "helps us shift our mindset from thinking that certain children are not thriving to thinking that the systems around children are not fostering thriving," according to Project 100 team member Alexis Wielunski, a program director at the Center for Care Innovations.

[caption id="attachment_30911" align="alignright" width="300"] Russian River flowing in the Sonoma County town of Guerneville, California (Norm Lane)[/caption]

A federally qualified health center (FQHC), West County Health Center serves more than 11,000 patients of all ages in rural western Sonoma County across 10 sites. Although West County Health is not the health care provider for all the approximately 100 babies born in the lower Russian River area each year, said Bauer, “We asked ourselves how can we support collective action to make sure that all 100 get what they need?”

To help answer that question, in the last half of 2023 the three convening organizations in Project 100 invited people from all sectors of the community to contribute their experience. And over the last year they’ve worked on a systems mapping project to help them figure out the barriers to care.

During the process they learned that some participants in the first systems mapping workshop were skeptical, “Like, ‘Oh, here we go again’; I understand that because there’s just such a pattern of people being excited and trying to start something and then it fizzles out.” But despite their reservations, Bauer said, “people were very, very engaged” – something that she saw increase as time went on.

[caption id="attachment_30910" align="aligncenter" width="627"]

Russian River flowing in the Sonoma County town of Guerneville, California (Norm Lane)[/caption]

A federally qualified health center (FQHC), West County Health Center serves more than 11,000 patients of all ages in rural western Sonoma County across 10 sites. Although West County Health is not the health care provider for all the approximately 100 babies born in the lower Russian River area each year, said Bauer, “We asked ourselves how can we support collective action to make sure that all 100 get what they need?”

To help answer that question, in the last half of 2023 the three convening organizations in Project 100 invited people from all sectors of the community to contribute their experience. And over the last year they’ve worked on a systems mapping project to help them figure out the barriers to care.

During the process they learned that some participants in the first systems mapping workshop were skeptical, “Like, ‘Oh, here we go again’; I understand that because there’s just such a pattern of people being excited and trying to start something and then it fizzles out.” But despite their reservations, Bauer said, “people were very, very engaged” – something that she saw increase as time went on.

[caption id="attachment_30910" align="aligncenter" width="627"] Dr. Jason Cunningham talking at Project 100 workshop (Credit: West County Health)[/caption]

The group created a map that’s a blueprint for understanding and reshaping the “nurturing” of early childhood in the lower Russian River area. Out of 1,000 forces that the workshop group identified on sticky notes, 44 were consolidated into themes. What the convening organizations then did, as part of systems mapping, is to create “loops,” she explained. “If there’s a theme around parental drug use, for instance, we say, well, what are the things that contribute to parents’ drug use? It could be low wages, layoffs or other things that contribute to homelessness. And that contributes to less bonding with your baby.”

Through the systems mapping, the group learned that community residents urgently needed both formal and informal support. This included food, health and education services as well as informal family, neighborhood connections and parents group support – and many people were just not getting them, which affected family and household well-being.

“The mapping process helped us understand the specific forces in our community that impact the ability of a household to create a safe and stable, nurturing environment and the ability to create the buffering and support their babies’ brains and bodies as they get started,” Bauer said. “We know from the research that that is critical for early development.”

If a family cannot access care and support, its trajectory may continue to be negative, she says -- “and we really want to shift that by creating stable and nurturing environments for those babies.”

Dr. Jason Cunningham talking at Project 100 workshop (Credit: West County Health)[/caption]

The group created a map that’s a blueprint for understanding and reshaping the “nurturing” of early childhood in the lower Russian River area. Out of 1,000 forces that the workshop group identified on sticky notes, 44 were consolidated into themes. What the convening organizations then did, as part of systems mapping, is to create “loops,” she explained. “If there’s a theme around parental drug use, for instance, we say, well, what are the things that contribute to parents’ drug use? It could be low wages, layoffs or other things that contribute to homelessness. And that contributes to less bonding with your baby.”

Through the systems mapping, the group learned that community residents urgently needed both formal and informal support. This included food, health and education services as well as informal family, neighborhood connections and parents group support – and many people were just not getting them, which affected family and household well-being.

“The mapping process helped us understand the specific forces in our community that impact the ability of a household to create a safe and stable, nurturing environment and the ability to create the buffering and support their babies’ brains and bodies as they get started,” Bauer said. “We know from the research that that is critical for early development.”

If a family cannot access care and support, its trajectory may continue to be negative, she says -- “and we really want to shift that by creating stable and nurturing environments for those babies.”

Turning the Curve

By the second workshop, even the skeptics in the community seemed to be feeling energized and excited, according to Bauer. [caption id="attachment_30913" align="aligncenter" width="562"] Participants in the Gaining Clarity session of Project 100, held in July 2023, ponder their choices for the journey map. (West County Health)[/caption]

Participants peppered the map with sticky notes to mark their reactions. By doing so they located bright spots in the community where things were happening, Bauer said, “or there was energy around particular issues, which could really ripple out if we addressed them. People put stickies everywhere. And afterwards we had everyone stand back to see what stood out to them, ‘what looks interesting, what has energy and what looks really frozen. And where did they think would be a place we could focus on?’ The 17 leverage points were narrowed down to six, including proactive screening for maternal and child health, addressing family stressors, and elevating community voices.

Community voices are more important now than ever, say advocates. “Project 100 looks at what is needed in the community and how we could do it more intentionally,” says Soledad Figueroa, director of River to Coast Children’s Services, which provides counseling, newsletters, low-cost car seats, emergency food and supplies, and vouchers for safe, equitable child care to low-income families in the lower Russian River area.

“Many of our Latino families are very isolated,” she says. “Buses only run a few times during the day, and lots of people live a couple miles or more from a bus stop. They may not have a car or gas money or be able to easily walk a couple miles to the bus stop with a baby and a small child so that they can access services or resources. And there is also isolation due to language and the lack of culturally competent care.” With the torrent of anti-immigrant rhetoric from rightwing U.S. politicians, some of the Latino families that River to Coast serves feel “scared and vulnerable,” she says.

In addition, some new Latino parents in the area are struggling with a new kind of family separation, she noted. One mother fleeing persecution recently crossed the border with her family and was processed for entry to the United States along with her daughter. However, her husband and young sons, who were traveling with her, were barred from entry. “The judge said the reason that only the mom and daughter were approved is because they were only admitting females,” Figueroa said. Now the mother is isolated and working around the clock to save money to help her husband and children left behind.

“At this point we really need more mental health services in Spanish and other languages for our community,” she said. “It is not something the Latino community traditionally looks for, but it is also a service that is hard to find. And the stress on our families is too great.”

Figueroa also hopes the proposed recreation center is built soon – “it’s not a good idea to leave teenagers with nothing to do all summer,” she said ruefully. Her hope is that Project 100 will find additional funding and continue to push forward.

Participants in the Gaining Clarity session of Project 100, held in July 2023, ponder their choices for the journey map. (West County Health)[/caption]

Participants peppered the map with sticky notes to mark their reactions. By doing so they located bright spots in the community where things were happening, Bauer said, “or there was energy around particular issues, which could really ripple out if we addressed them. People put stickies everywhere. And afterwards we had everyone stand back to see what stood out to them, ‘what looks interesting, what has energy and what looks really frozen. And where did they think would be a place we could focus on?’ The 17 leverage points were narrowed down to six, including proactive screening for maternal and child health, addressing family stressors, and elevating community voices.

Community voices are more important now than ever, say advocates. “Project 100 looks at what is needed in the community and how we could do it more intentionally,” says Soledad Figueroa, director of River to Coast Children’s Services, which provides counseling, newsletters, low-cost car seats, emergency food and supplies, and vouchers for safe, equitable child care to low-income families in the lower Russian River area.

“Many of our Latino families are very isolated,” she says. “Buses only run a few times during the day, and lots of people live a couple miles or more from a bus stop. They may not have a car or gas money or be able to easily walk a couple miles to the bus stop with a baby and a small child so that they can access services or resources. And there is also isolation due to language and the lack of culturally competent care.” With the torrent of anti-immigrant rhetoric from rightwing U.S. politicians, some of the Latino families that River to Coast serves feel “scared and vulnerable,” she says.

In addition, some new Latino parents in the area are struggling with a new kind of family separation, she noted. One mother fleeing persecution recently crossed the border with her family and was processed for entry to the United States along with her daughter. However, her husband and young sons, who were traveling with her, were barred from entry. “The judge said the reason that only the mom and daughter were approved is because they were only admitting females,” Figueroa said. Now the mother is isolated and working around the clock to save money to help her husband and children left behind.

“At this point we really need more mental health services in Spanish and other languages for our community,” she said. “It is not something the Latino community traditionally looks for, but it is also a service that is hard to find. And the stress on our families is too great.”

Figueroa also hopes the proposed recreation center is built soon – “it’s not a good idea to leave teenagers with nothing to do all summer,” she said ruefully. Her hope is that Project 100 will find additional funding and continue to push forward.

The Path Forward

Chris McCarthy is the founder of the Innovation Learning Network Coaching & Consulting (ILN) and a longtime partner and advisory board member of CCI. A systems thinking and human-centered design expert who worked for years at Kaiser Permanente and HopeLab and calls himself “a change rebel for good,” he coaches numerous clients, one of which is Project 100. Asked what it was like to coach Project 100, where the three convening organizations all share equal power, McCarthy smiled. “Normally, I would predict deep complications, but it was just the opposite,” he said. ‘Rather than competing, the three groups all complemented each other beautifully. This has been a dream collaboration, where it’s really about the mission. The community is not overly large and it’s very tight-knit, and their dollars for impact are more precious to them. I feel that they’re thinking more wisely and keenly about how to use those resources.” [caption id="attachment_30925" align="alignleft" width="394"] A young patient in a dental chair at West County Health Centers (Credit: WHCH)[/caption]

He particularly enjoyed holding a workshop about leverage points -- “a very important systems concept.” McCarthy had all the participants try to keep a spoon level while holding it at the very end of the handle, using only a thumb and index finger. “It’s nearly impossible to hold a spoon that way, although holding it in the middle is very easy." There was a lot of laughter and dropped spoons during the exercise, he said. "It was a lot of fun, and they fully understood the concept by the end – 'find the leverage points that will make the most difference!'”

McCarthy also had kudos for the convening organizations, which put together the systems map after the workshops. “As the core team, they created the map, which is often a deeply frustrating experience. It’s very, very hard work and an emotional roller-coaster. But they created space for both frustration and joy,” he said, adding that the finished map was enthusiastically received.

At present, a new organization that emerged alongside Project 100 from the initial Design Jam -- the County Connection and Research Group -- has been working hard to strengthen connections between people and neighborhoods in the community. It just submitted an application with the Ag & Open Space District in Sonoma County to build a new park in Guerneville, and eventually, a new community center. It's also in the early stages of planning Design Jam #2.

Meanwhile, Bauer is applying for grants which, if successful, could sustain Project 100 for years. And beyond the initial focus on Project 100, our work together, she says, “is building community capacity for this under-resourced community to be resilient to face challenges in the future.”

[caption id="attachment_30916" align="alignright" width="300"]

A young patient in a dental chair at West County Health Centers (Credit: WHCH)[/caption]

He particularly enjoyed holding a workshop about leverage points -- “a very important systems concept.” McCarthy had all the participants try to keep a spoon level while holding it at the very end of the handle, using only a thumb and index finger. “It’s nearly impossible to hold a spoon that way, although holding it in the middle is very easy." There was a lot of laughter and dropped spoons during the exercise, he said. "It was a lot of fun, and they fully understood the concept by the end – 'find the leverage points that will make the most difference!'”

McCarthy also had kudos for the convening organizations, which put together the systems map after the workshops. “As the core team, they created the map, which is often a deeply frustrating experience. It’s very, very hard work and an emotional roller-coaster. But they created space for both frustration and joy,” he said, adding that the finished map was enthusiastically received.

At present, a new organization that emerged alongside Project 100 from the initial Design Jam -- the County Connection and Research Group -- has been working hard to strengthen connections between people and neighborhoods in the community. It just submitted an application with the Ag & Open Space District in Sonoma County to build a new park in Guerneville, and eventually, a new community center. It's also in the early stages of planning Design Jam #2.

Meanwhile, Bauer is applying for grants which, if successful, could sustain Project 100 for years. And beyond the initial focus on Project 100, our work together, she says, “is building community capacity for this under-resourced community to be resilient to face challenges in the future.”

[caption id="attachment_30916" align="alignright" width="300"] A screening at West County Health Centers can be fun (West County Health)[/caption]

“There’s a saying in public health that “what's predictable is preventable," she said. “That's echoed in our work to prevent the impacts of toxic stress in our community. It is predictable that unbuffered toxic stress in early childhood significantly increases the risk of poor outcomes over the lifespan. You can predict what's going to happen. With Project 100, we're seeking to get to the root cause of what makes us sick and identify community solutions to address those needs.”

And that can open the door to transformation.

“We are working to create a culture where we examine current systems and decide if we are willing to accept the status quo. Humans have created systems and humans can change systems,” said Bauer. “And we can do that together by seeing those places where the systems aren't working and trying new things that fit – within the resources and the culture of our community.”

She and others in Project 100 call this model “right-fit solutions.” In other words, Bauer says, “what's going to work in the lower Russian River is not necessarily what's going to work in San Francisco or Berkeley. We must figure out what is going to work for the lower Russian River.”

One advantage is the small size of the target population, Bauer notes. “The relatively small number of babies born each year has created an enticing ‘hook’ to engage community members in challenging the status quo,” she said. “Focusing on one hundred babies creates some intrigue: With a small number like this, it is like a test. Can we really knit ourselves together? Can we make sure that every family has a car seat? It's not like 20,000 babies, and you’d need to find a warehouse! But here we could ask every group involved in Project 100 to be responsible for two car seats, and we’d have enough.”

It takes a village, as they say. And the lower Russian River seems particularly receptive to this small but ambitious project.

“I think it does come down to culture, and one of the reasons why I was interested in doing Project 100 in this area,” Bauer says. “There was already the feeling that we're sort of on our own out here and we’ve got to help each other. There has been a real thirst for connection after COVID. People are eager to reconnect. And if we succeed, it could really change lives.”

A screening at West County Health Centers can be fun (West County Health)[/caption]

“There’s a saying in public health that “what's predictable is preventable," she said. “That's echoed in our work to prevent the impacts of toxic stress in our community. It is predictable that unbuffered toxic stress in early childhood significantly increases the risk of poor outcomes over the lifespan. You can predict what's going to happen. With Project 100, we're seeking to get to the root cause of what makes us sick and identify community solutions to address those needs.”

And that can open the door to transformation.

“We are working to create a culture where we examine current systems and decide if we are willing to accept the status quo. Humans have created systems and humans can change systems,” said Bauer. “And we can do that together by seeing those places where the systems aren't working and trying new things that fit – within the resources and the culture of our community.”

She and others in Project 100 call this model “right-fit solutions.” In other words, Bauer says, “what's going to work in the lower Russian River is not necessarily what's going to work in San Francisco or Berkeley. We must figure out what is going to work for the lower Russian River.”

One advantage is the small size of the target population, Bauer notes. “The relatively small number of babies born each year has created an enticing ‘hook’ to engage community members in challenging the status quo,” she said. “Focusing on one hundred babies creates some intrigue: With a small number like this, it is like a test. Can we really knit ourselves together? Can we make sure that every family has a car seat? It's not like 20,000 babies, and you’d need to find a warehouse! But here we could ask every group involved in Project 100 to be responsible for two car seats, and we’d have enough.”

It takes a village, as they say. And the lower Russian River seems particularly receptive to this small but ambitious project.

“I think it does come down to culture, and one of the reasons why I was interested in doing Project 100 in this area,” Bauer says. “There was already the feeling that we're sort of on our own out here and we’ve got to help each other. There has been a real thirst for connection after COVID. People are eager to reconnect. And if we succeed, it could really change lives.”