How many times have you been coached to:

- Learn from your mistakes?

- Fail fast and early?

- Rapidly prototype?

- Or develop a growth mindset?

As a person often providing this advice, and struggling to follow it, I have found some clarity in my recent experiences as a quality improvement leader at Kaiser Permanente and my first months as Executive Director at the Center for Care Innovations.

Failure as Rocket Fuel

My first inspiration starts close to home with 3-year-old puzzle making. This is a hard puzzle for my daughter Maya (even when her twin sister Liora helps).

Maya’s success in this puzzle does NOT depend on her spatial relations skills. She succeeds because she rapidly she tries her ideas, fails, and learns. It takes Maya 50 seconds to find a piece that fits. She fails 11 times before she succeeds. Many of her guesses aren’t great, but it doesn’t matter. She doesn’t overthink each idea (or do a PowerPoint or ask permission): she just tries it. She doesn’t mourn or feel bad each time a piece doesn’t fit: her cost of failure is zero. She quickly sees what doesn’t work, and moves on, until piece-by-piece she completes the puzzle.

Just think about the projects you’ve led that involved months — or years — of planning without a single prototype to test assumptions or whether you’re on the track to meet customer needs.

How often has the urgency for results, or over-investment in our ideas, driven us to go big and experience high-cost failures? Or to rationalize our middling results?

We can bring Maya’s clarity in “assembling a truck puzzle” to our big messy, inspirational adult projects, and craft solutions with same shame-free, experimental mindset.

Pumping Failure Fuel into Organizational DNA

As Steve Spear documented, Toyota has an organizational DNA that defines how they deliver astounding results. With practice, we can build fertile failure into our organizational DNA. Let’s start in two areas where a humble learning mind-set is super critical:

- The Big Flop

- Testing and prototyping

The Big Flop (or Sentinel Event)

A Big Flop, or a serious event (including patient harms that require regulatory or accreditation reporting), is often a major opportunity for systemically changing operations to improve care, or services.

But, as Amy C. Edmonson has found, organizations have major challenges avoiding the blame game in these situations: even though executives estimate that a failure is blameworthy only 2 to 5 percent of the time, they say their organizations treat them as blameworthy 70 to 90 percent of the time. Social psychologists have documented this Fundamental Attribution Error experimentally for over 40 years: we are much more likely to blame people rather than their situation. As American children age they blame people rather than situations more than children from other cultures, possibly incorporating American’s self-reliance values.

One of my proudest experiences at The Permanente Medical Group (Kaiser Permanente’s northern California medical group) was how our clinical leadership and my team responded to a major failure of our regional colorectal cancer screening poop test kit outreach system. Our team was responsible for reliably sending out kits and reminder messages in the name of physicians. The overall program has reduced colon cancer incidence by 52 percent.

In 2012, we discovered that over a five-month period we had sent test kits or messages to over 50,000 members late, early, or in the wrong sequence. For example, we sent reminder messages to complete a poop test to members before we sent the test; or, we took a month to send a kit after we sent a letter from the member’s physician that the kit would arrive in a week. Members started complaining to their physicians and medical center staff. It took a while, but we finally stopped dismissing the complaints from medical centers and realized we had a big problem.

We could have blamed a single individual who didn’t follow procedures (which was actually true!); instead, we acknowledged that this important clinical process for over 500,000 members should not depend on one person’s infallibility. We described to leadership how our system had failed, and how we were going to figure out why, and then make it incrementally better, addressing the biggest risks first. Remarkably, our senior quality leaders did not take off our heads or look for an easy fix.

Too often, the required Root Cause Analysis (RCA) process used in health care leads to weak retraining, policy writing, and accountability solutions: “RCA results in the tombstone effect: though its purpose is to guard against a similar incident in the future, it may instead function primarily as a procedural ritual, leaving behind a memorial that does little more than allow a claim that something has been done.”

Ultimately, we didn’t find a single root cause to this failure. But rather we used this big failure to transform our improvement and operations approach. We built new technology and more reliable operations incrementally through dozens of small tests. We made it vastly easier for medical center staff to reach us. We gave members a phone number to a dedicated support team that would listen to them, but then work with us to rapidly diagnose and fix problems.

Rapid Testing and Prototyping

This brings us back to Maya. As my daughter Maya showed in building her truck puzzle, the more rapidly (and safely) that you can reject wrong ideas, the faster you reach your goal. It is NOT easy for us to let go of our great ideas, and it is NOT easy for leaders to set clear goals and let their teams figure out exactly how to get there.

A great deal of popular science has described how we become less creative as we grow up. Organizations and people can practice and improve their innovative thinking and creativity. (Our Catalyst and Safety Net Innovation Network programs are a core part of our mission.) I think the missing jewel in this research, though, is the finding that children are better at experimenting without fear of failure.

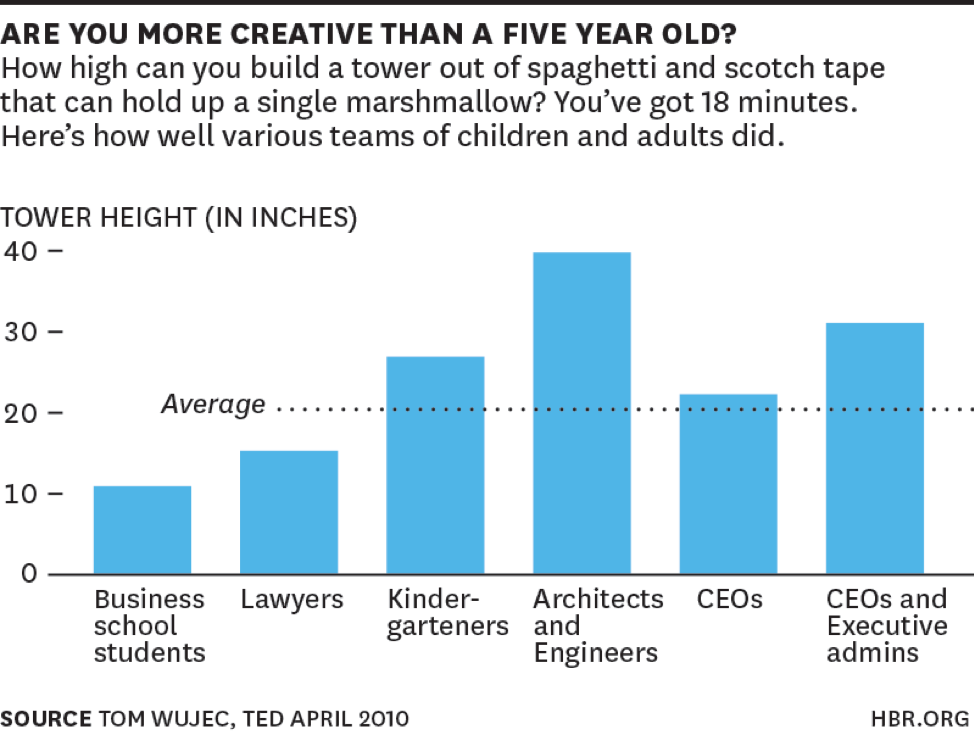

One of the most vivid illustrations of the rapid prototyping skills of children is Tom Wumec’s Marshmallow Challenge. Teams of four have 18 minutes to build the tallest possible free-standing structure, with a marshmallow on top, using a yard of masking tape and 25 sticks of spaghetti. Based on dozens of iterations, Wumec found that kindergarteners built taller towers than CEOs, lawyers, and business school students. Only architects and engineers (technical knowledge does matter sometimes!) and CEOs with executive admins built taller towers than kindergarteners.

The Marshmallow Challenge kindergartners start trying structures with the marshmallow on top right from the start; the business school students plan and compete for whose ideas are best for almost the whole time, testing only at the end.

As we age, we start to know lots of stuff; and, our advancement depends, or we think it depends, on our smart ideas being correct. We too quickly dismiss or are not open to ideas that contradict what we already believe. We don’t rapidly test our assumptions before proceeding with long implementation planning cycles.

In my first months at CCI, I had the chance to visit many Federally Qualified Health Centers where leaders make a deep investment of their time and organizational resources to support rapid learning on the way to achieving strategic goals:

- At West County Health Centers, I met Dana Valley, Associate Director of Quality Management, who built and supports a results reporting and improvement system for strategic quality goals: every care team and medical assistant reflects on their testing successes and failures each month and ideas they will try next. Dana’s team makes it easy for teams to see on run charts how their ideas work or don’t work.

- Brenda Johnson, CEO, and Ida Saito, COO, at La Clinica in Medford, Oregon showed our Population Health Learning Network site visit team their improvement system, Ease in the Change, which they designed to build full team ownership of the problem and opportunity, testing and failure, and spread and sustain process. They described their initial ideas as “standard work version 1.0.”

What can I do today?

As with exercising your creativity muscles, there are specific behaviors we can practice every day to make us more humble puzzle solvers:

1. Create a process for second order problem solving.

At times of major crises (e.g. natural disasters, new product failures) our strongest tendency is to move to crisis management, blame someone, or find and try solution (like retraining), and move on. We owe it to our customers to use these big bad failures (plus our smaller misses) as occasions for understanding and testing solutions to core problems.

Our big failure with poop test kit outreach at Kaiser Permanente led to a new process called a SPA (Systematic Preventive Action). For small failures, we used the one-hour SPA template. For big ones, we had the one-week SPA template.

2. Cultivate challenging assumptions and alternative viewpoints.

Make your leadership, product, improvement teams more diverse and actively cultivate a speak-up culture. Research has consistently found that these teams might feel less comfortable, but perform better. Reserve time in decision and solutioning meetings for team members to talk about what could go wrong, or to unpack the assumptions behind the conclusion. Create a designated skeptic in the team meetings and rotate the role.

At CCI we are experimenting with team huddles twice per week, adapting the daily huddles often used in organizations pursuing Lean management. One huddle focuses on identifying and addressing problems in today’s or this week’s work. The second huddle focuses on raising longer term ideas. By protecting just 15 minutes each week, and looking for every staff person to share their perspective, we now have a much richer view of our true challenges and opportunities.

3. Manage your words and actions to value productive failure, always.

Even one blaming statement in a stressful failure situation can undermine many months, or years, of culture change efforts. As an influential leader, no matter what your level of authority in your organization, people are watching you. What do you say and do when failure happens? How do you approach developing a new product?

At Kaiser Permanente, our regional clinical outreach and technology teams created rapid customer feedback or prototyping systems. We started noticing a lot more failures that were invisible before: we could see now when puzzle pieces didn’t fit. When my team reported a failure to me, they would often look embarrassed or sad. I worked to actively control my body language and words. I would smile and say:

- “That is a great discovery! How did we find this out?”

- “That is great that our early warning system caught this before it affected many [or any] members.”

- “What is your thinking about mitigating any effects on customers?”

- “How are you thinking about doing a SPA to learn about and address the cause?”

- “This is great news! Now we can fix the problem!”

4. Create a rapid testing village in your team.

It is not easy to change away from a culture focused on PowerPoint development, planning meetings, leadership sign-offs, and top-down deployments. As you start to empower your team, make it everyone’s job to shrink big changes into small tests to accelerate your project, program, or product.

At CCI, our team is trying to make it easier for the teams we support in Kaiser Permanente’s PHASE in the Community program to test changes: how can they find ideas, inspiration, tools, and contacts more quickly? Could we build an easily navigable virtual change package? Our team members were excited, but appropriately skeptical, on the assumptions behind this big idea. They shrunk the work into a series of small tests to transform our cardiovascular care content that we have begun already.

If you are successful changing your failure culture, your team will start pushing back at you saying something like “stop analyzing it so much, just try it!”

Find this useful or interesting? We’re constantly sharing stuff like this. Sign up to receive our newsletter to stay in the loop.