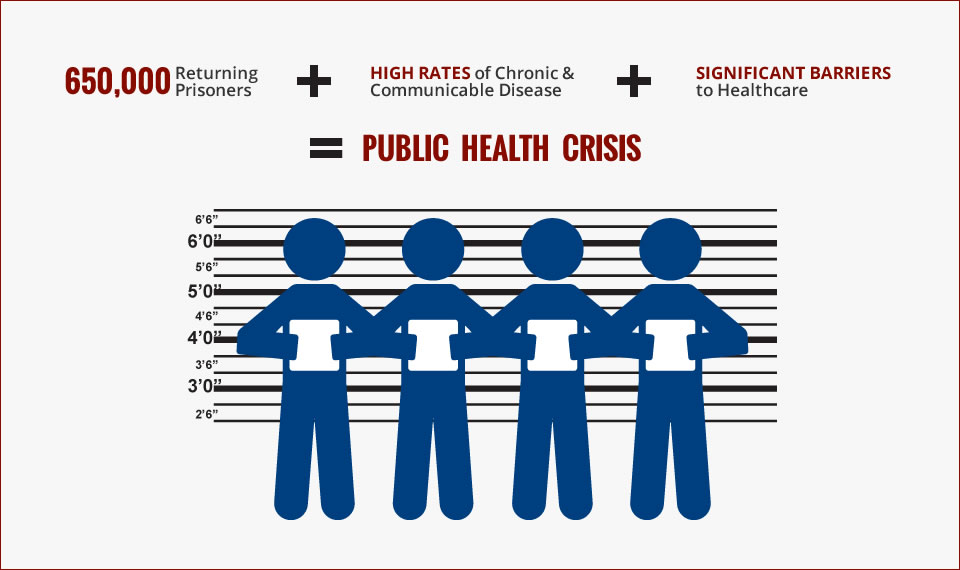

In 2006, a group of San Francisco physicians recognized that the health care system wasn’t meeting the needs of people coming home from incarceration. Individuals were being unnecessarily hospitalized and dying due to a lack continuity of care from the prison to the community.

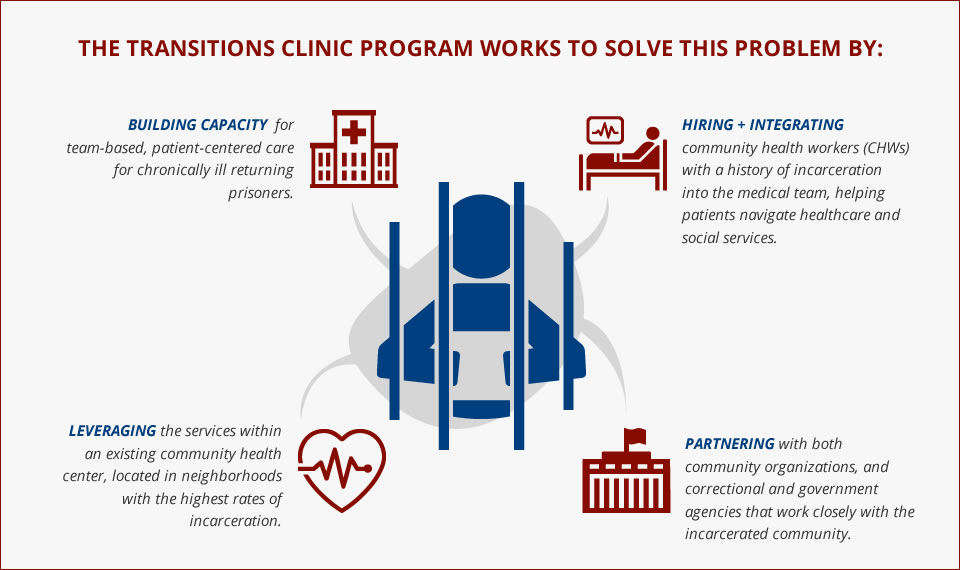

So this group of changemakers launched the Transitions Clinic program. In partnership with the local community, Services for Prisoners with Children, City College of San Francisco, UCSF, and the San Francisco Department of Public Health, they developed a new model of care that provides:

- Integrated program within current primary care team to provide care appropriate to recently released individuals and their families.

- Specially trained community health worker (CHW) with past history of incarceration to assist with patient navigation, care management, and chronic disease self-management support, as well as provide culturally competent care.

- Patient centered services. This includes access to primary care within two weeks of release, behavioral health integration, medication assisted treatment for substance use disorders, re-entry support, and more.

- Partnerships with criminal justice systems and existing community organizations that serve formerly incarcerated individuals to address healthy re-integration and prevent re-incarceration.

It was heralded as a model for other clinics across California. And today it’s grown into the Transitions Clinic Network, which supports clinics in 12 states and Puerto Rico in implementing this model.

We talked with Executive Director Shira Shavit and Program Manager Anna Steiner to learn more.

Your co-design process is one of the reasons why we’re so inspired by you guys. From the start, you reached out to the community to help you build this new model of care. What did you learn?

SHIRA: When anybody does this work, you are very well-intentioned, and you may have what seem to be really good ideas. But then when you share those with people who are actually utilizing the services or impacted by the system, sometimes you realize that your ideas may be missing the mark. One example that was early on was that in San Francisco we had an offer from the county jail to utilize some space that they had across the street from the facility that would have allowed for people coming out of jail to get health services immediately upon release. From a clinical perspective that seemed like a really great idea: People would leave the jail, they could come across the street get their medications filled, and then they could get their health needs addressed. But when we floated that idea by the community advisory board and people we were working with, they all actually thought it was a terrible idea. They said, “Nobody’s going to go across the street. They want to get as far away from the jail as possible.” It was a really stark reminder that without having experienced incarceration, you really don’t understand some of the struggles that people face.

It’s also where the idea of having a community health worker with a history of incarceration being embedded within the primary care team came from. The community said we really need to focus more on health and wellbeing, not just on the individual physical health conditions — which was at that time with the focus of primary care — but really to expand to address their mental health, their behavioral health issues, and then all of the social determinants of health.

And what became apparent to me over time was just how much mistrust people had of the health system that came both from their experiences prior to incarceration and then also during incarceration. It became very clear that people were not comfortable engaging with the health system without having somebody embedded within that system who that had shared experience, who they could trust, who they could really connect to.

Was it difficult to recruit community health workers? Was that same mistrust also a barrier for hiring?

SHIRA: By already including community members early in the design process, we were able to utilize that for the hiring process. The word was out in the community that we were looking for someone good for the position. So, I think it just really underscores that in this program, traditional hiring models, like posting on Craigslist or some online forum, are really not the best way to get individuals for these positions.

At the same time, you’re creating a pipeline of jobs into the health care field. How is this helping communities heal?

SHIRA: That’s a major goal of our organization — create more opportunities for people impacted by the criminal justice system. And as you know, having a criminal record makes it much more difficult for people to get employment, especially in the health care sector. And I think what our work has shown over time is that kind of flies in the face of the belief that people coming out of incarceration have nothing to give to the community. In fact, we’ve proven the opposite — people coming out have so much to give. They’re able to leverage their own experiences and their passion to give back to their own communities.

What does prison do to a person’s health?

ANNA: Something that we struggle with is that most systems don’t screen people to find out if they have been incarcerated. Providers may not know unless patients feel emboldened and empowered to share that information.

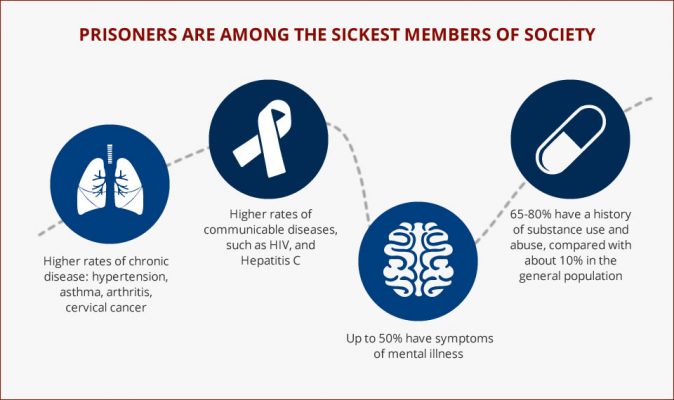

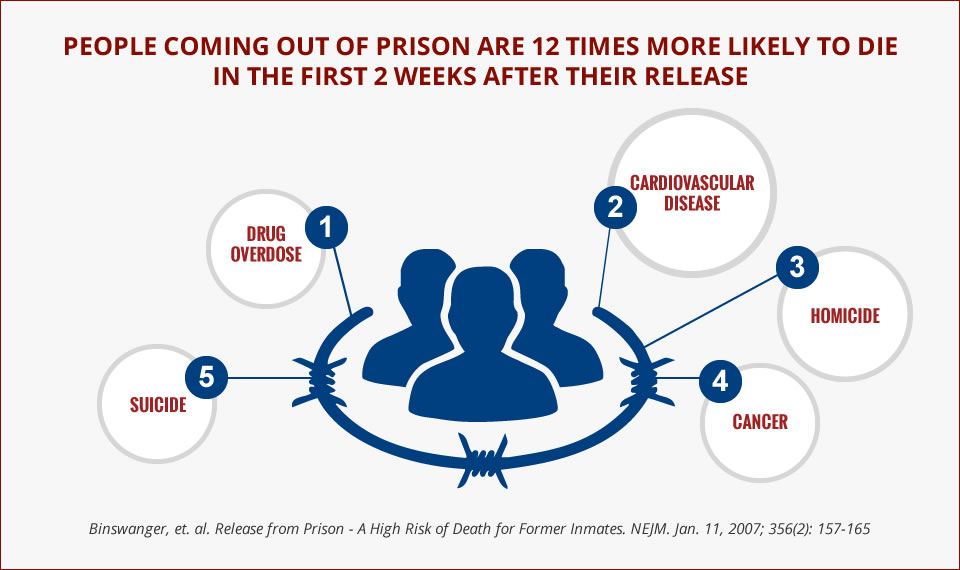

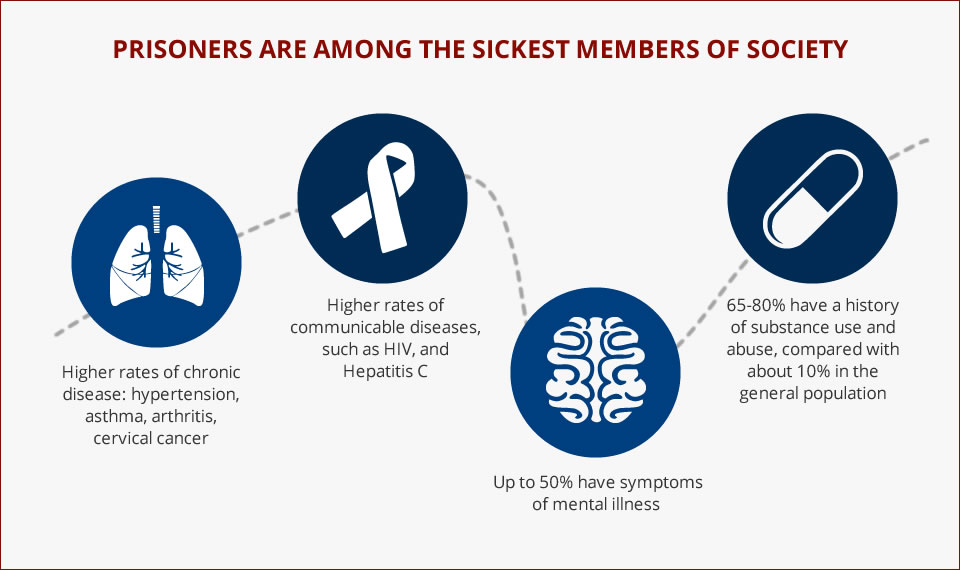

As for some of the major health concerns: People impacted by the criminal justice system have higher rates of chronic medical conditions and behavioral health conditions. The incarcerated setting can precipitate or exacerbate these conditions — You don’t have many choices around what you eat or when you exercise. Another thing that’s very specific to people who’ve been incarcerated, both exposure to violence and solitary confinement. These conditions can lead to patients have post-traumatic stress disorder or something that we’ve been calling “post-incarceration stress syndrome.” So, there’s claustrophobia post release. A lot of people develop anxiety or panic that’s associated with being having been in small spaces. For example, once released it may be difficult to get on a crowded train or bus. We know there’s a higher rate of substance this disorder among these patients and overdose is actually the number one cause of death upon release. The population is also aging. Aging is actually accelerated when you’re incarcerated. When we’re talking about incarcerated populations, 55 is considered geriatric. So, there’s this weathering process that happens with people in prison due to the conditions and increased stress.

SHIRA: Also, we see higher rates of transmission of infectious diseases. Hepatitis C is a really good example. It has been documented to be up to 40 percent in our state prison system, as compared to 2 percent in our general population. That’s because we have people inside who are sharing needles for IV drug use and tattooing. Because they don’t have access to methods like harm reduction and clean needles, there’s a very high spread of these communicable diseases. People are also living in very close quarters. For instance, if there’s a flu outbreak, they’re much more likely to be exposed.

What’s the impact of your model of care?

SHIRA: In one randomized controlled trial that we performed here in San Francisco, we saw that individuals coming out of prison who engage with our program were 50 percent less likely to use the emergency department as compared to the control. Subsequent studies have shown that individuals in our program are less likely to be hospitalized for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. When they are hospitalized, they’re hospitalized for almost a full day less as compared to controls. And we also have seen that individuals in our program are less likely to have a technical violation for probation or parole. And for those who are reincarcerated in the first year post-release, they spend a significant less amount of time in jail as compared to their counterparts., we’re seeing a real impact on both health outcomes and some criminal justice outcomes of these individuals.

You’re forging relationships with correctional partners and reentry organizations. Why is it so important to go beyond the four walls of the clinic?

SHIRA: People coming out of incarceration have really complex, comorbid diseases — very high rates of substance use disorder, mental health diagnoses, as well as chronic medical conditions. When people come out of incarceration all of the social determinants of health really are up in the air. They don’t have a place to live. They have don’t have a way to make money and may not have access to food. They may not be reconnected with family. These are all of the pieces that people need in their lives to be stable and healthy. So, if health systems really want to move the needle and improve health outcomes for these patients, you really have to think more broadly about what really impacts health. But in order to do that, it really requires transformation at the system level.

The Transitions Clinic Network was founded to better help clinics implement this model. We realized that this is quite a deep process that requires clinics to transform how they practice. They have to change their systems. They have to do things differently. They have to be able to open those clinic walls to better bridge across multiple systems such as the community social services and the criminal justice system. In order to do that, it requires changing business as usual.

What did it take to grow into a network that spans 12 states and Puerto Rico?

SHIRA: When we just started doing this work, our colleagues around the Bay Area started reaching out saying, “Hey, we’ve heard about this. Tell us more.” So, we started informally sharing with colleagues. And then we came to the realization that this really is system transformation. It requires much more than a few conversations. So, we thought maybe we should formalize the process and not only create training and coaching material to help clinics, but connect them together. The best innovations that have come out of our work have come from all of the different sites that have taken this core model, implemented it within their own settings, and adapted it to the needs of their own communities. This is where we’re learning from each other as a network.

What innovations are you testing?

SHIRA: We utilize data in order to determine where to innovate. For example, in one of our studies looking at our patients across 13 sites, we saw surprisingly high rates of food insecurity among people coming out that were correlated with higher ED visits and hospitalizations. As a result, many of the sites have worked with their local food banks to have food pantries on site at their clinics and implemented cooking classes where they teach individuals coming home from incarceration how to use food pantry items to prepare meals. We realized this was really critical when you have somebody who’s been incarcerated either for a long period of time or in and out of the system of incarceration; they may have had little experience in cooking or shopping for themselves.

Another innovation that we are disseminated across sites, came after one of our sites started sending their community health workers into the jail to meet with individuals prior to release. The jail had been making appointments for these individuals for primary care post release and only 33 percent of people were showing up. And after the community health workers started meeting with the clients inside, the show rates went to 70 percent.

What advice would you give to clinics wanting to start this work?

SHIRA: Engage the community in the work from the beginning. Embed the community health workers into the primary care team and create good structures of supervision to support them. Facilitate them providing input and feedback at every step of the implementation process as well as in the daily care of patients. They are the experts and that’s the reason we call our community health workers our “special sauce.”

Find this useful or interesting? We’re constantly sharing stuff like this. Sign up to receive our newsletter to stay in the loop.