For our Population Health Learning Network (PHLN), CCI is providing the opportunity to the 25 participating teams to visit one of six organizations that are exemplars in at least two aspects of population health management. The goal is to provide both inspiration and the practical, nitty gritty details needed to help PHLN teams take action and move their own population health work forward.

Recently, we visited to Cherokee Health Systems in Knoxville, Tennessee, and I learned firsthand about its inspiring integrated model that brings together behavioral and primary health care.

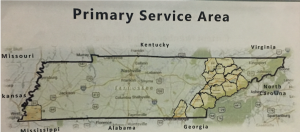

Cherokee is an FQHC that was initially established in 1960 as a community mental health center. It has grown to provide a blend of primary care and behavioral health services in 48 clinical locations across Tennessee. The organization focuses on low-income and medically underserved populations, serving as a provider for a patient base of nearly 78,600 individuals. In 2015, the National Committee for Quality Assurance honored its whole health approach and recognized the organization’s work as a Patient-Centered Medical Home.

During our site visit, we took a deep dive into Cherokee’s integrated care model, addiction medication program, homegrown Bio-Psycho-Social Assessment, NextGen customization, and care coordination.

Here’s what I learned:

Integrated care is an ideology and culture, not a service or a program.

Cherokee believes deeply that integration isn’t a checkbox, but a means to an end. Its end goal includes improved health outcomes of a population, health equity, improved access, a focus on wellness and prevention, patient-centered care, and evidence-based clinical and program decision-making.

To Cherokee, an integrated model has the following characteristics:

- Shared care delivery functions across a team of primary care providers and behaviorists.

- Guaranteed access to behavioral health expertise “wherever behavioral problems show up,” whether that’s in a behavioral heath visit, primary care visit, or elsewhere.

- Improved communication and care coordination.

- Expanded health management support.

- Supported patient engagement.

Behavioral health and primary care staff are equally responsible for closing gaps in physical care.

Cherokee believes that when you bring a behaviorist into the flow of health care from the start, it helps that behaviorist be seen as part of the overall team. Then, when behavioral issues arise, it becomes easier and more streamlined to involve behaviorists. But that also means that behavioral health has to assume responsibilities outside of their official scope of practice. For example, when a behaviorist looks at a patient dashboard and sees that patient is overdue for a mammogram, it’s their responsibility to talk to the patient about the lapse in care. Cherokee has trained their staff to “look at the red and fix it,” meaning it’s up to everyone to close gaps in care, based on the patient dashboard they’ve developed and customized in NextGen.

Cherokee believes that when you bring a behaviorist into the flow of health care from the start, it helps that behaviorist be seen as part of the overall team. Then, when behavioral issues arise, it becomes easier and more streamlined to involve behaviorists. But that also means that behavioral health has to assume responsibilities outside of their official scope of practice. For example, when a behaviorist looks at a patient dashboard and sees that patient is overdue for a mammogram, it’s their responsibility to talk to the patient about the lapse in care. Cherokee has trained their staff to “look at the red and fix it,” meaning it’s up to everyone to close gaps in care, based on the patient dashboard they’ve developed and customized in NextGen.

Cherokee also believes that behavioral health has to practice like primary care. What that means is that integrated behavioral health must fulfill should follow the four C’s of primary care: contact, comprehensive, coordinated, and continuous. Behavioral health must be ready to deal with anything that comes through Cherokee’s doors, be organized and synchronized with other elements of care, and fit within the context of a longitudinal partnerships.

Some of the key features of Cherokee’s integrated model include:

- A behaviorist on the primary care team.

- A consulting psychiatrist on the primary care teams.

- Shared panel and population health goals.

- Shared support staff, physical space, and clinical flow.

- Shared clinical documentation, communication, and treatment planning.

Cherokee offers addiction medicine as part of its continuum of services.

Cherokee started as a community mental health center and as such, has always offered some sort of addiction support services, including traditional intensive outpatient treatment. But two years ago, they expanded the support they offer by starting a medication-assisted treatment, or MAT, program. The opioid crisis has hit Cherokee hard; currently there’s an average a one death per day in their county from opioid-related causes. Cherokee recognized that the crisis was particularly playing out in its women’s health department, where pregnant women need access to MAT. Its MAT program provides services geared toward addressing mainly alcohol and opioid addiction; since launching, Cherokee providers have treated 443 patients, 80 percent for opioids and 20 percent for alcohol. They have encountered a few challenges and successes with their program including:

- No-show rates. Initially, they had a 90 percent no-show rate for their MAT groups. However, once they added a pharmacist and the opportunity to refill medications during the group visits, their no-show rate decreased to 5 percent.

- Waiver restrictions. Tennessee is currently the only state where Nurse Practitioners and RN’s cannot be waivered to prescribe opioid addiction medication like buprenorphine. Currently only four Cherokee providers are waived, and there is only one provider actively seeing patients and prescribing. There is still a reluctance from providers to get waived, despite education efforts on the part of their provider champion. As they wait for more providers to get waived, they have hired two Certified Peer Recovery Specialists to provide support and can bill for some of the services they provide.

Cherokee makes its integrated model work regardless of payment.

According to their CEO Dennis Freeman, Cherokee’s guiding philosophy is “do the right thing and the money will follow.” Given their patient and payor mix (30 percent of their patient population is uninsured; the State of Tennessee did not expand Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act), Cherokee is often experimenting with different and innovative ways of providing care, and then finding ways to pay for services. One of their seven organizational strategic emphases include to “go where the grass is brownest” meaning that a core priority is to go where the need is greatest. For example, they recently opened a clinic in Memphis. If you’re not familiar with the local geography, Detroit, Michigan, is closer to Knoxville than Memphis. There are no direct flights between the cities, and the drive is about six hours. But there was a need in Memphis for the kind of care they provide, and so they committed to expand their services, despite logical and geographic challenges.

With regards to population health management, according to their CEO, “you can’t afford not to do it,” and by “do it,” he means that as we move toward value-based payment, safety net health care organizations need to learn how to manage populations by closing gaps in care, investing in IT and data capacities to help close those gaps, and better manage and coordinate care. He pointed out that Cherokee has $1.2 million in incentive payments to gain or lose depending on how well they can close care gaps and achieve quality measures; that money can be used to help provide services to their large uninsured population.

Lots of time on the EHR backend saves on the frontend and provides the right pathway that makes clinical sense.

For years, the IT department heard the No. 1 complaint from clinicians when using their EHR was cumbersome documentation. Based on this feedback, IT decided to move toward an EHR that focuses on entering discreet data points versus narrative responses and IT built out completely customized interfaces and reports. Today, Cherokee has developed a patient dashboard that provides up-to-date and accurate patient data, and its centralized care coordination team uses daily outreach reports to identify gaps in care and non-compliant patients. The success of Cherokee’s data and IT systems and tools stems from the inclusion of clinical leadership from both primary care and behavioral health and designing systems that work for clinical staff.

They’ve developed a Bio-Psycho-Social Assessment (BPSA) that they use to guide the care they deliver.

Cherokee has 35,000 assigned Medicaid lives, and are engaged in several value-based contracts with their payors put them at risk for quality target and cost targets. This forces them to ask:

- Who are these patients? What is driving their use of services?

- Who are the sickest and what resources do they need?

To answer these questions, Cherokee has developed a Bio-Psycho-Social Assessment (BPSA) to account for patient complexity. The BPSA quantifies patient complexity from biological, psychological, and social domains. Points are assigned to conditions and combined into an overall score. The following domains include:

- Patient information: Includes general patient information like age, income, BMI, language, living arrangements, appointments, no show rate, and care plan engagement.

- Claims data: Includes medical and behavioral health diagnoses, prescriptions, BHC visits, and hospital in-patient and ER use.

- Social factors: Includes non-medical needs that are discussed at intake. For patients not seen, social factor scores are estimated based on that patient’s zip code.

The BPSA took two years for Cherokee to get right. But now that the system has been developed, it’s easy to update and provides accurate data at the point of care. Developing the BPSA was an upfront investment, and Cherokee continues to work hard to get claims data, but the payoff is that it produces a score that is displayed on each assigned patient’s dashboard and is used by care teams to close gaps in care.

Telemedicine of “part of everyday life at Cherokee.”

Staff at Cherokee remarked that they are often asked to give presentations on their use of telemedicine, but they find it challenging to decipher and distinguish telemedicine for the way they normally provide care. They use telemedicine both in the clinic and outside of the clinic, to link patients to specialists as well as Cherokee staff that might be located elsewhere. For example, their Director of Primary Care Services, Dr. Febe Wallace, lives and sees patients via telemedicine from her home in Lexington, Kentucky. Beyond telemedicine, Cherokee is working toward developing an app that will work just like Uber; you can request to videoconference with a provider when you need it. Although they wouldn’t be able to bill for encounters generated through the app, they see it as an ER diversion tool and a way to continue to extend care to patients outside the four walls of their clinic. Whether telemedicine or an app, Cherokee stressed the importance of mobility in integrated care: all of their staff have and use laptops, and all have 4G enabled Wi-Fi, so that they can access their EHR and patient dashboard whether providing care in the clinic, in patients’ homes, or elsewhere in the community.

Staff at Cherokee remarked that they are often asked to give presentations on their use of telemedicine, but they find it challenging to decipher and distinguish telemedicine for the way they normally provide care. They use telemedicine both in the clinic and outside of the clinic, to link patients to specialists as well as Cherokee staff that might be located elsewhere. For example, their Director of Primary Care Services, Dr. Febe Wallace, lives and sees patients via telemedicine from her home in Lexington, Kentucky. Beyond telemedicine, Cherokee is working toward developing an app that will work just like Uber; you can request to videoconference with a provider when you need it. Although they wouldn’t be able to bill for encounters generated through the app, they see it as an ER diversion tool and a way to continue to extend care to patients outside the four walls of their clinic. Whether telemedicine or an app, Cherokee stressed the importance of mobility in integrated care: all of their staff have and use laptops, and all have 4G enabled Wi-Fi, so that they can access their EHR and patient dashboard whether providing care in the clinic, in patients’ homes, or elsewhere in the community.

Cherokee’s mission is to provide quality training opportunities to both their staff and others in the safety net.

Over the years, as people learned about Cherokee’s system of integrated care, they wanted to come and learn firsthand from the organization. People asked to shadow providers, but so much shadowing created a strain on provider/patient relationships. Cherokee realized that it needed to streamline the way they responded to requests. So it developed a training academy, and now offer nine, two-day onsite learning programs per year. To date, the organization has trained individuals from all 50 states and shared its experience in clinics across the country. Recognizing provider shortages (especially in rural areas, where they operate many of their clinics) and the need to develop providers and behaviorists to serve safety net populations, their training academy is key mechanism to inspire and train the current and future generations of safety net providers.

Quick communication, not long meetings.

Despite not believing in meetings, there is culture of collaboration that starts at their executive level and extends into care teams. Care teams have many different tools to communicate and coordinate care, including their patient dashboard, morning huddles, via the EHR, weekly integrated team meetings, and standing orders. Their executive leadership believes in shared decision-making, but also that they often can’t wait for weekly meetings to make decisions. As such, they often make decisions by “mini” communication through 1- to 2-minute check-ins that are quick and efficient. Short emails and text messages are used in place of adding agenda items to meetings scheduled a week out.

“The Cherokee Way.”

While visiting Cherokee, we learned that to be a successful employee, you need to be willing and able to wear many hats; “You have to be a swiss army knife.” During our site visit, we heard time and time again that resistance to providing truly integrated care was not “the Cherokee Way.” And that when hiring, they look for flexibility, fit with culture and values, and then competency. In fact, the CEO was said to have two core jobs: (1) being the guardian of the organizational mission, and (2) the Chief Talent Scout. The average tenure of Cherokee staff is 25 years.

Cherokee is an inspiring place to visit and an exceptional organization to learn from. The staff are leaders and innovators in delivering patient-centered care, from using cutting edge technology to stressing the importance of relational care. To learn more, visit www.cherokeehealth.com, which has information on the many training academies offered throughout the year.

Find this useful or interesting? We’re constantly sharing stuff like this. Sign up to receive our newsletter to stay in the loop.