Why do we treat addiction so differently than we do all other chronic diseases?

Addiction support group and counselor

That was the question Dr. Joe Sepulveda posed to his audience at a recent CCI webinar. A board-certified psychiatrist specializing in addiction treatment at the Family Health Centers of San Diego, he founded the organization’s Medications for Addiction Treatment program and oversees the program throughout the organization’s 23 primary healthcare clinics, seven behavioral health facilities, 14 different substance abuse treatment centers, and its mobile Clean Syringe Exchange Program.

In our May 19 webinar, he urged primary care providers to embrace addiction treatment as they do diabetes, hypertension, and other common chronic diseases: without bias or judgement. Watch the recording and view the slides below, and continue reading for our main takeaways.

Here are some of the main takeaways:

1. Addiction treatment suffers from decades of stigma – and that has to change.

Sepulveda contrasted the non-judgmental treatment offered primary care patients with chronic diseases like diabetes or hypertension with that offered people with an opioid use disorder – something that usually results in a quick referral to a drug treatment center. “It’s long been known that stigma is a big component as to why treatment for addiction has suffered,” Sepulveda said. “It’s traditionally been approached as a social problem, not as a health problem. But the reality is that it’s actually a chronic disease.”

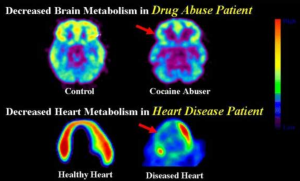

An underlying change in a biological structure indicates disease. (Courtesy: Joe Sepulveda, MD)

2. Addiction is a chronic disease of the brain

“The question I always get is, ‘Well, how do you know it’s a chronic brain disease?’” said Sepulveda. “First, when there’s a disease of the brain, you have a behavioral expression of it.” He pointed to Alzheimer’s, whose classic presentation is memory loss, and to schizophrenia, which involves unusual perceptions of reality and mood changes. For opioid use disorder, Sepulveda said, the classic presentation is cravings, which lead to uncontrollable compulsive use.

“But before all these symptoms develop, there are some fundamental long-term changes in biological structures, such as the brain,” he said. “For example, these PET imaging slides [see above] show that in someone addicted to cocaine, the green fluorescence indicating [healthy metabolism] has dissipated on the brain image to the right. And in a healthy heart, you’ll see a red glow, indicating healthy tissue, but if there is a heart attack or atherosclerotic plaque – some underlying disease of the heart – it will show up on the right-hand side as well. So in both addiction and a traditional medical condition, you have an underlying change in a biological structure, which indicates a disease.”

3. Addiction has a robust genetic component

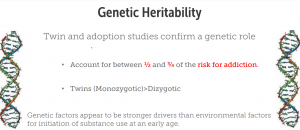

“From twin and adoption studies, we know that genetics plays a role in addiction,” Sepulveda said. “Based on those studies, we know that about a half to three quarters of the risk of becoming addicted to a substance comes from just genetics alone.”

He noted that identical twins, for instance, have a higher tendency to display a genetic predisposition to addiction than do fraternal, or dizygotic, twins, who develop from two different eggs. “It means that if you have a genetic predisposition for developing an addiction, those twins that have identical genetic codes will have a much higher rate of developing an addiction whereas those that do not have the same genetic code,” Sepulveda said. “And this is a very strong factor. It appears that this genetic predisposition has stronger drivers than environmental factors for initiating substance use, particularly at a young age.”

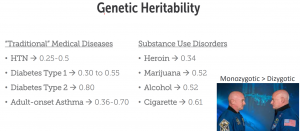

4. The genetic predisposition to addiction rivals that of many other chronic diseases.

Sepulveda showed the audience a chart that listed hypertension, diabetes (Types 1 and 2), and adult-onset asthma on one side, and substance disorders involving heroin, marijuana, alcohol, and cigarettes on the other (see illustration, below), along with numbers indicating the genetic contribution to the disease. (Zero meant there was no genetic component whatever.) For example, the genetic predisposition for hypertension is 0.25 to 0.5, while the genetic predisposition of developing alcoholism is 0.5. “You can see the numbers are pretty comparable,” Sepulveda said. “It’s no different if you compare the genetic predisposition of developing hypertension, diabetes, and asthma to that of someone developing an addiction to a substance.”

_________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________

5. The neurobiology behind addiction has been well mapped out.

Sepulveda began by discussing the amygdala, or “reptilian brain” — structures primed for the survival instinct in which dopamine plays a key role. “Crocodiles, for example, don’t have a developed brain like humans – they have a reptilian brain. They snap at something because they learn that with each snap the chance they will catch food is high and that’s a pleasurable experience, and dopamine is what drives that reward,” Sepulveda said.

“If the memory part of the brain remembers the experience as euphoric or pleasurable, it will drive the reptilian brain to want more and more of that. And we can see in imaging studies that the executive parts of the brain – the part that can reason and say no – are overwritten when the reptilian brain is driven. They’re just shut down. In essence, a person who has an addiction really doesn’t have control over their decision-making process or use patterns. It’s a disease; it’s an illness; and they’re driven to it.”

6. An addiction can happen to anybody

“It’s not just genetics or neurobiology – everyone is susceptible to developing an addiction if they are prescribed chronic opioid therapy,” Sepulveda said. “The reason we got into the opioid epidemic in the first place was the overprescribing of prescription opioids in order to treat the ‘fifth vital sign.’ [pain]. We thought it was okay to give opioids for an extended period of time. Well, what we found out is that if you give people chronic opioids, you can have as high as a 50% prevalence rate for developing an opioid use disorder over time.”

“We also know that it’s not just the length of time– it’s also the dose or strength of the opioid that’s going to make it more likely for you to develop an addiction,” he said. When people were on opioid therapy for more than 90 days at greater than 120 morphine equivalents, Sepulveda added, they were 100 times more likely to develop an opioid use disorder than those who were not. These findings, he adds, are among the reason physicians now recommend against using opioids for acute pain for more than 5 days.

7. In addiction cravings cannot be controlled

Sepulveda showed imaging of the brain of someone addicted to cocaine – a brain that looked normal until the person was shown cues and images of people using the substance. “That’s when the amygdala [the reptilian brain] lit up,” he said. “The person does not have control over this; they need help.”

To illustrate what craving and compulsive use feels like, he used an example of a patient quoted in USA Today. “Imagine yourself with this person, who is shaking their head and trying to hold back tears. And they say, ‘It’s like if God tells you that if you take another breath, your children will die. And you do everything, anything, not to take a breath, but eventually you do. That’s what it’s like. Your brain just screams at you.’”

Sepulveda invited members of the audience not to take a breath. ‘It’s impossible: As much volition and intent as you have, your brain is going to override that and you’re going to take a breath,” he says. “That is what it feels like to have an addiction.”

8. Providers should continue to support patients when they relapse

“People are savvier now, but I still occasionally hear, “Addiction was a choice because they chose to try the drug, so it’s their fault –why should I care?’” said Sepulveda. “Well, voluntary misuse doesn’t make this condition any less of a disease. If you chose to have a poor diet or work at a job that requires you to sit lots of hours, you’re going to be more likely to develop a health condition, whether that’s a heart condition or diabetes or Alzheimer’s. Nonetheless, the doctor or whoever is treating the condition is still going to treat that condition because they know it’s an illness – even if some personal life choices may have contributed to its development.”

He continued that “I also hear sometimes, ‘Well, you know, they relapse, they’re not really committed to this,’ and it leads to people being kicked out of programs. Again, if you approach this through the lens of a chronic disease, we have relapse rates with diabetes and other diseases of anywhere from 30% to 70% — similar to addiction — yet somehow we work with the patient and meet them where they’re at. We need to show that same understanding to people with substance use disorders, to remember that the brain takes time to heal.”

9. Medications for opioid use disorder allow people to lead a healthy life.

“One thing you will commonly hear is that medications for opioid use disorder is substituting one drug for another,” Sepulveda said. “And someone who says that doesn’t really understand what medications for opioid use disorder are doing. These really are medications that make a huge amount of difference, not just with the patient, but with the patient’s families and restore them back to normal functioning. They also do a great job of decreasing mortality. The biggest thing that people need to realize is that we need to approach this illness with heart and compassion.”

10. Providers need to build trust

“Remember that these patients [with an addiction] have dealt with stigma for most of their life,” he said. “They’ve been shunned by institutions. They’ve been shunned by emergency departments when they needed help. So they have this wall for their own self-protection. The first thing that you need to do with this population is to build trust. If the patient is not ready to implement the amount of change you want, you need to build up trust and a relationship. That will eventually morph into the patient feeling that they can not only come to you for what they need, but also that you have their best interest at heart. And that will win them over to make change.”

Further Reading

Tackling America’s Deadliest Drug Epidemic: How CCI Helped Transform Addiction Treatment During the Pandemic. March 15, 2021.

CCI and Partners Develop Effective New Tool for Primary Care Clinics Rolling Out Medications for Addiction Treatment, May 17, 2021.

Systems Thinking Reveals New Pathways for an Addiction Treatment Coalition. February 28, 2021.

Find this useful or interesting? We’re constantly sharing stuff like this. Sign up to receive our newsletter to stay in the loop.