We’re ramping up our work on addiction treatment with the launch of three new programs aimed at increasing access to medications for addiction treatment, also known as MAT, for opioid use disorder.

MAT is the use of Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for opioid, alcohol, and opioid use disorders. These medications can be used on their own, as well as in combination with psychosocial therapies, to support recovery from substance use disorders.

To walk us through this approach, we talked with Dr. Brian Hurley, our clinical director for Addiction Treatment Starts Here: Primary Care

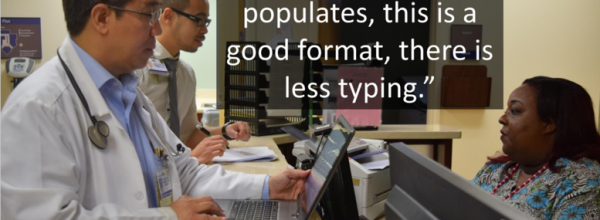

You’ve said that the first step to understanding substance use disorders — and in particular, opioid use disorder — is recognizing that they are treatable chronic brain diseases. Why is that?

Prior to the development of medications for addiction treatment, there wasn’t anything other than support and counseling available to people with substance use disorders. Because of this legacy, the reflex from primary care has historical been to refer patient with opioid use disorder to treatment outside of primary care clinics — patients would be told to go to talk to somebody else about their substance use.

But now we have validated medications feasible for use in primary care settings. Medications for opioid use disorder have tremendous efficacy and many patients respond, even in the absence of the counseling and psychosocial support that we typically arrange for people with other types of the substance use disorders. So, this has really changed the framing of opioid use disorder — which has always been a chronic brain condition — because we hadn’t previously had medication tools feasibly offered in primary care to address them. Medications for opioid use disorder are can be effectively prescribed in a routine primary care and can make a huge impact on people’s lives.

So that’s why I start with opioid use disorder as a chronic brain condition that responds to medications. I think this framing helps people understand that primary care providers can offer treatment that have a big impact on the public health impact of the opioid epidemic in a way that wouldn’t have been possible before the development of these medications.

How exactly does MAT treat opioid use disorder?

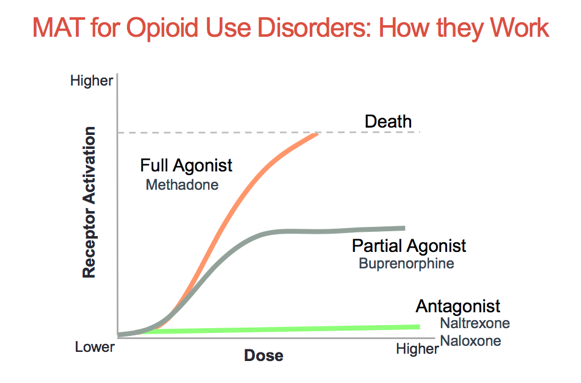

Medications for opioid use disorder treat opioid use disorder by stabilizing the opioid receptor systems in the brain that are dysfunctional. However, each of the three FDA-approved molecules have different mechanisms.

Methadone is a “full agonist” — the more you take, the more effect it has on your opioid system. The role of methadone in opioid use disorder is to induce tolerance so that people with opioid use disorder stop using their problem opioids because methadone makes them tolerant.

Buprenorphine works very differently than methadone. Buprenorphine does give you a partial opioid activation, but strongly binds and blocks opioid receptors, so it blunts the effects of other opioids.

And then naltrexone blocks opioid receptors, and because the opiate receptors in your brain are bound and occupied, but not activated, people use less of their problem opioids.

At the same time, the best practice for treatment of chronic conditions require both pharmacologic and lifestyle interventions. How does MAT go beyond just medication?

Medication, counseling, and support are the three active components of opioid use disorder treatment.

Most chronic conditions that have behavioral components. Treating opioid use disorder is not unlike treating diseases of obesity. With obesity, somebody needs counseling on knowing what to eat, how to maintain exercise and other physical activity, and they might need medications for their heart disease or their hypertension or their diabetes that might be associated with their obesity. But they also need support. Even if you have all the diabetes prevention skills in the world and are on an anti-diabetic medication, if everyone in your household eats cake all day long, you’re probably still going to have high blood sugars because it’s hard to eat appropriately in that kind of environment. So, I think all three — medications, counseling, and support — are really important in any kind of behavioral medicine condition.

When should providers start MAT?

When a patient with an opioid use disorder is identified, the medication should be first, before the patient is referred for specialized counseling. Opioid use disorder can be quickly lethal, so if providers withhold a medication to stabilize their opioid receptors in their brain, there is six times the increased risk of death. So that’s why I always recommend starting with the medications first.

But medications first does not need medication only. It just means that you stabilize somebody’s opioid brain system, so you break the cycle of intoxication and withdrawal. Or you stabilize the brain, so patients can build a program of recovery on top of the stabilization that medications have given them, where they can begin to pursue other types of counseling and support recovery activities.

Fewer than 10 percent of people across the country actually receive this kind of treatment for opioid use disorder. What’s stopping more patients from accessing MAT?

There are three big reasons.

The first is organizational capacity. Most addiction treatment has been siloed away from general health care. We fund it and regulate it as a separate branch of health care, and patients have learned to expect that their addiction treatment will be separate from the rest of their health care. And so, trying integrate addiction treatment technologies back into general health settings is dissonant with the organizational silos that have been historically developed and ossified to separate addiction treatment from other health services. There’s a lack of widespread organizational capacity to systematically identify opioid use disorder in primary care and rapidly treat patients with opioid use disorder. Opioid use disorder can be quickly fatal. However, there is a perception issue of addiction as a social problem, not a medical problem. By way of illustration, if a patient presents to the emergency department with opioid use disorder, the standard is, “Leave here and go to a treatment program,” rather than, “Let’s start using a medication right now.” Health care treats cardiac attacks — which can also be quickly fatal — very differently. We quickly get an EKG to monitor that person. We quickly provide medications to relieve the stress on the heart, so that it lowers the risk of death associated with a heart attack. We quickly mobilize medical treatments. With people with an opioid use disorder, even if they’re identified, we don’t always get toxicology testing and rapid ignition of appropriate medications like we would with any other condition with comparable risk of death.

And even if there is a clinician who is interested in prescribing a medication for opioid use disorder, there are a variety of organization barriers including that the pharmacy may not stock the appropriate medication for opioid use disorder, or the nurse may not be familiar with how to administer it, or the medical record doesn’t easily let you document this service. Many health care facilities don’t build a system the same system around opioid use disorder as is available for the other types of potentially fatal medical conditions.

The second reason is individual provider readiness. Individual providers have their own attitudes and beliefs. Even if you can get an organization to build appropriate processes, individuals in that organization don’t always follow established processes. A lot of people have their own beliefs surrounding opioid use disorder that aren’t evidence-based. I’ve had conversations with otherwise excellent clinicians who tell me, “I don’t ever want to prescribe” a medication for opioid use disorder. It’s not because of lack of information about evidence supporting the use of these medications, but instead comes from preconceived attitudes around the treatment of people with opioid use disorder with medications.

The third big reason that medications are underutilized is patient readiness. Now oftentimes the treatment gap sometimes looks as though it’s the fault of the treatment community for not capitalizing on opportunities. But addiction is a really unique health condition because most of the people that have opioid use disorder either don’t think that they have it or aren’t ready — at a given moment — to do anything about it.

One of the big studies out of a National Survey on Drug Use and Health looks at people who didn’t get treatment. Ninety five percent said, “Because I didn’t want treatment.” Addiction treatment historically is available only when patients are ready to commit to abstinence. But many of our patients will be dead before they’re ready for abstinence from all non-tobacco intoxicants. So, we need to lower the threshold of when and how people can access medications for opioid use disorder, so that people can get medication first. One of my colleagues in Northern California oftentimes says, “Look, don’t ask people about their opioid use. If they’re not ready to tell you that they use opioids inappropriately, they’re just not going to tell you. But one of the big game changers is to make sure that people know that if they ask for medications for opioid disorder, that you’ll offer it to them.” And that can make a big difference — make sure that people know that medications are available, and they can start them without many contingencies or barriers.

Right now, we’re witnessing an evolution in language, as “medication-assisted treatment” has become “medications for addiction treatment.” Why the shift?

“Medication-assisted treatment” is paradoxically a stigmatizing term. It implies this idea that the medications are not themselves effective treatments, which is false. And it implies that in order to get medications for addiction treatment, you have to be enrolled in some separate program outside of primary care; that’s also not true. This phrase makes them sound somehow distinct from the other effective treatments that we routinely offer in medical care.

I understand that the term originated and developed out of the concept of highlighting the role of psychosocial treatment as the primary ingredient in substance use disorder treatment, and the medications are simply adjunctive to a psychosocial treatment. The evidence though says that medications for opioid use disorder can be tremendously effective on their own — even if somebody isn’t participating in a psychosocial treatment.

Calling it “medications for addiction treatment” begins to walk back some of that stigmatizing frame. So rather than these medications being implied as adjunctive to some other treatment, we call them what they are: medications for addiction treatment.

It’s the same as the way that we call anti-depressants medications for depression. Depression responds to psychosocial treatments and to medications. So, I don’t think there’s any real doubt about antidepressants themselves functioning as an active treatment. We could draw a similar analogy with metformin and insulin. These are both medications for diabetes. We don’t call them medication-assisted diabetes treatments. We call them medications for diabetes.

Using the term medications for addiction treatment destigmatizes, and in fact, it even normalizes the role of medication in the treatment of people with opioid use disorder.

What’s next on the horizon? Where is the field going?

I think that we’re going to continue to see the advent of additional medications to treat opioid use disorder and an eventual widespread application of these medications within general medical settings.

Despite the effectiveness of these medications, integrating psychosocial treatment delivered in primary care can go a long way not just for opioid use disorder, but for all kinds of behavioral conditions, particularly for depression and anxiety care. So, I think that integrated behavioral health care really an important next step in the treatment of opioid use disorders and other behavioral health conditions in primary care settings. Parallel care, where patients obtain physical health care at one facility and mental health care in another facility, is an outdated model. Delivering behavioral health care in the context of general medical settings is the winning strategy, because if effective, cheaper, patient centered, and reduces provider strain.

One thing that is going to help the spread of medications for opioid use disorder is providers experiencing how well they work. One of the historic concerns is that few clinicians outside of specialized settings prescribed these medications, and few in primary care knew many patients who were taking medications for opioid use disorder. These medications were seen as specialized and esoteric. But once a provider has prescribed these medications to four or five patients with an opioid use disorder, these historical perceptions melt away, which has a huge destigmatizing effect. This destigmatizing effect makes a big difference for provider readiness. It shifts these medications from being seen as esoteric and specialized technology to where primary care providers see just how feasible and effective medications for opioid use disorder are in primary care settings.

Find this useful or interesting? We’re constantly sharing stuff like this. Sign up to receive our newsletter to stay in the loop.