Tribal Partners and Community Health and Wellness

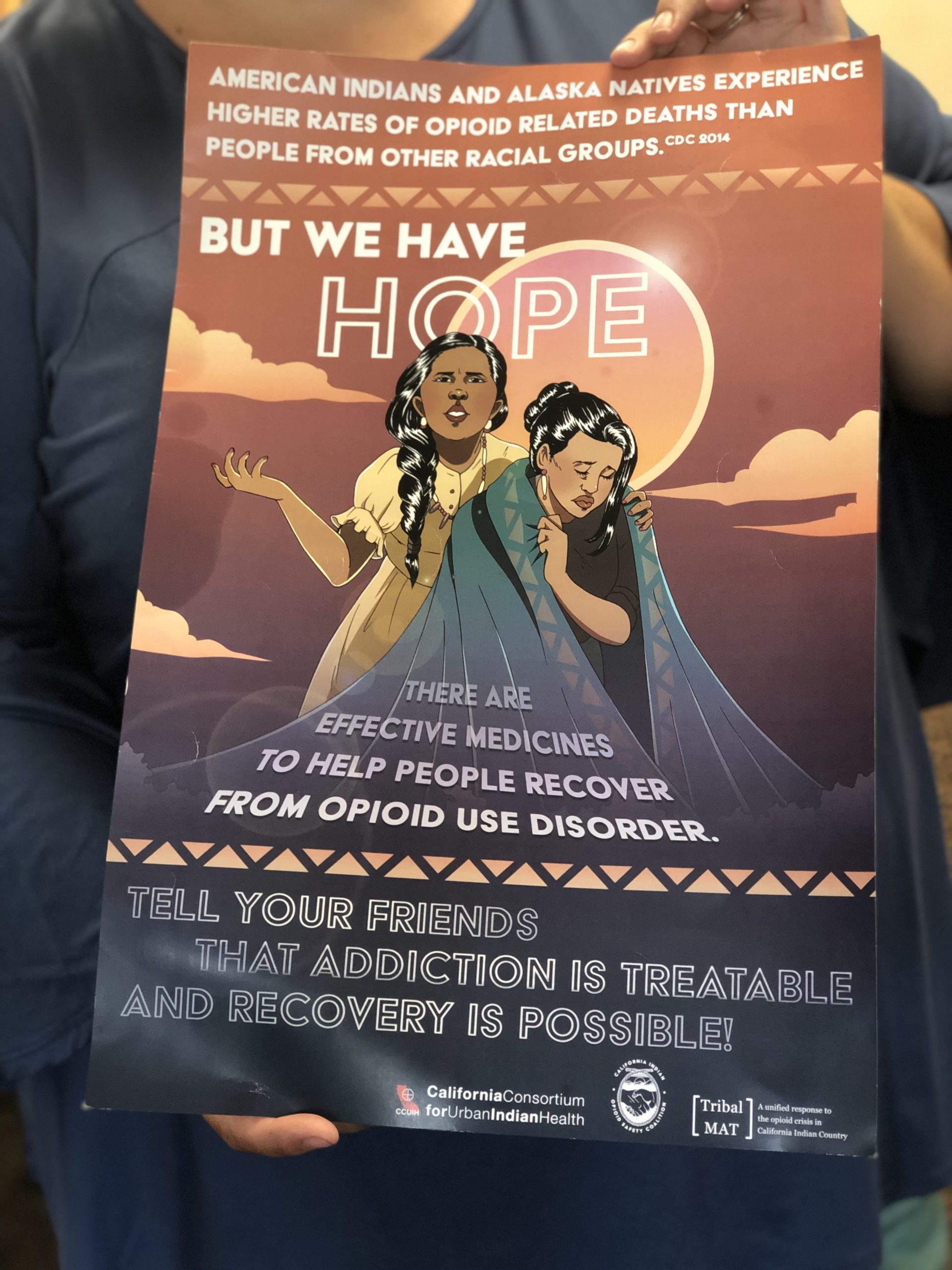

Founded in October 2017, Rx Safe Del Norte already had a grasp on the importance of education, stigma reduction, a holistic approach to treatment, and relationship building in facing this chronic concern. During this collaborative, the grassroots group learned more about the power of partnerships to help combat the problem. From its tribal members it learned how crucial it is to understand Native American sovereignty, tradition, stories, and hierarchy and their role in Indian culture and health. It also gained greater insight on generational and historical trauma, destruction of culture, and access to indigenous medicine and life ways. “Families are a big part of people’s recovery,” says Brubaker. “Historical trauma adds another layer to this work we need to consider and address.”

The coalition learned more about the diversity of its indigenous citizens too. “There is a lot of indigenous knowledge around wellness and pain management that needs to be respected by the community and medical providers,” says Brubaker. “And that wellness may look different to indigenous communities. People may not see the relationship of river health to a substance use disorder. But we know that our river health is directly related to the health of our indigenous people for various reasons — sustenance, cultural and family practices, social supports, the environment.”

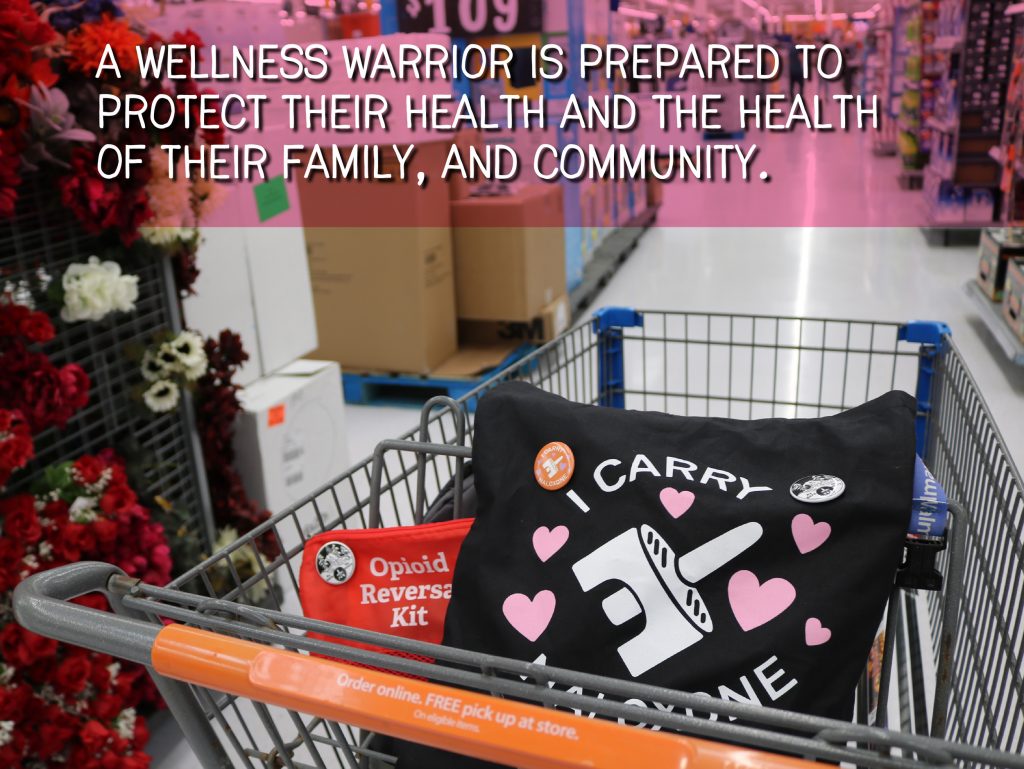

One of the coalition’s campaigns, Wellness Warrior, highlights indigenous wellness activities such as the making of a salve with wormwood or The Red Road, an indigenous alternative to substance disorder recovery programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous. “There is no Pan-Native American experience, even for those who are in the same region,” Brubaker notes. “Something that non-indigenous folks don’t understand is that each tribe and rancheria is a separate nation and has their own culture and governance that needs to be understood.”

These partnerships have been crucial to all the coalition’s work. “We are able to bring in people from all these different agencies to focus in on ‘how might we?’ make something like this happen — insert prototype idea here,” explains Brubaker. “This also helps build culturally appropriate services in our community, with indigenous agencies working with other non-native government agencies. These are the people who can give concrete input on how something would work in a day-to-day way.”

Dare to Think Big

The Del Norte coalition might represent a small community but it dreams big. When COVID-19 almost derailed many of the coalition’s plans to do outreach to educate, destigmatize, prevent, treat, heal, and save lives as part of this collaborative — from tabling events working with people with lived experience, to hosting a large, in-person health and wellness conference —the organization quickly changed course. Brubaker, the co-facilitator on the project, jokingly says the coalition went to “Zoom University” to make meetings a reality. They also turned to social media—hosting live events on Facebook, for instance—to reach key constituents. “COVID-19 put a big wrench in everything. We were forced to go the virtual reality road,” says Brubaker. “But it worked.”

Indeed, the shift had unexpected benefits. Beginning June 2020, a five-week wellness and recovery webinar series featuring 39 different events was held in partnership with California Rural Indian Health Board, Open Door Community Health Centers, United Indian Health Services, Yurok Tribe Health and Human Services, and Yurok Tribe Wellness Coalition. The webinar events were diverse: They included everything from panels on harm reduction and training with overdose-reversing medications such as naloxone, sessions on self-care, presentations on alternatives to opioids, and discussions on how to decolonize community interventions. The series was designed to educate the community, offer prevention tools, provide healing practices, and save lives. The virtual summit reached people beyond the county and helped the coalition form new relationships with first responders, elected officials, health care professionals, and people in recovery in Del Norte and neighboring Humboldt counties.

The newest relationship, with the California Rural Indian Health Board, helped strengthen loose partnerships, which enabled Rx Safe Del Norte to collaborate with more tribal organizations, according to Brubaker. The newest large connection, says Brubaker, was the Crescent City Police Department. The police chief attended a training and the coalition has partnered with the police department around naloxone training. The events helped build trust, solidify relationships, and helped to facilitate collaborations, she says.

Many of the event’s presentations, designed to appeal to professionals, frontline workers, and the general public, are now housed on the coalition’s YouTube channel. A panel on lived experience, which features Yvonne Guido, a certified substance use disorder counselor with Two Feathers Native American Family Services, and indigenous teenager Charlene Juan, has reached more than 1,300 viewers via Facebook — more than triple the viewership of most of the series sessions and far more observers than a typical in-person community conference here might attract.

Finding culturally appropriate speakers, promoting their presentations, and offering speaker fees was important to both Rx Safe Del Norte and its partners, notes Brubaker, of the virtual series that was much less costly to run than an in-person event.

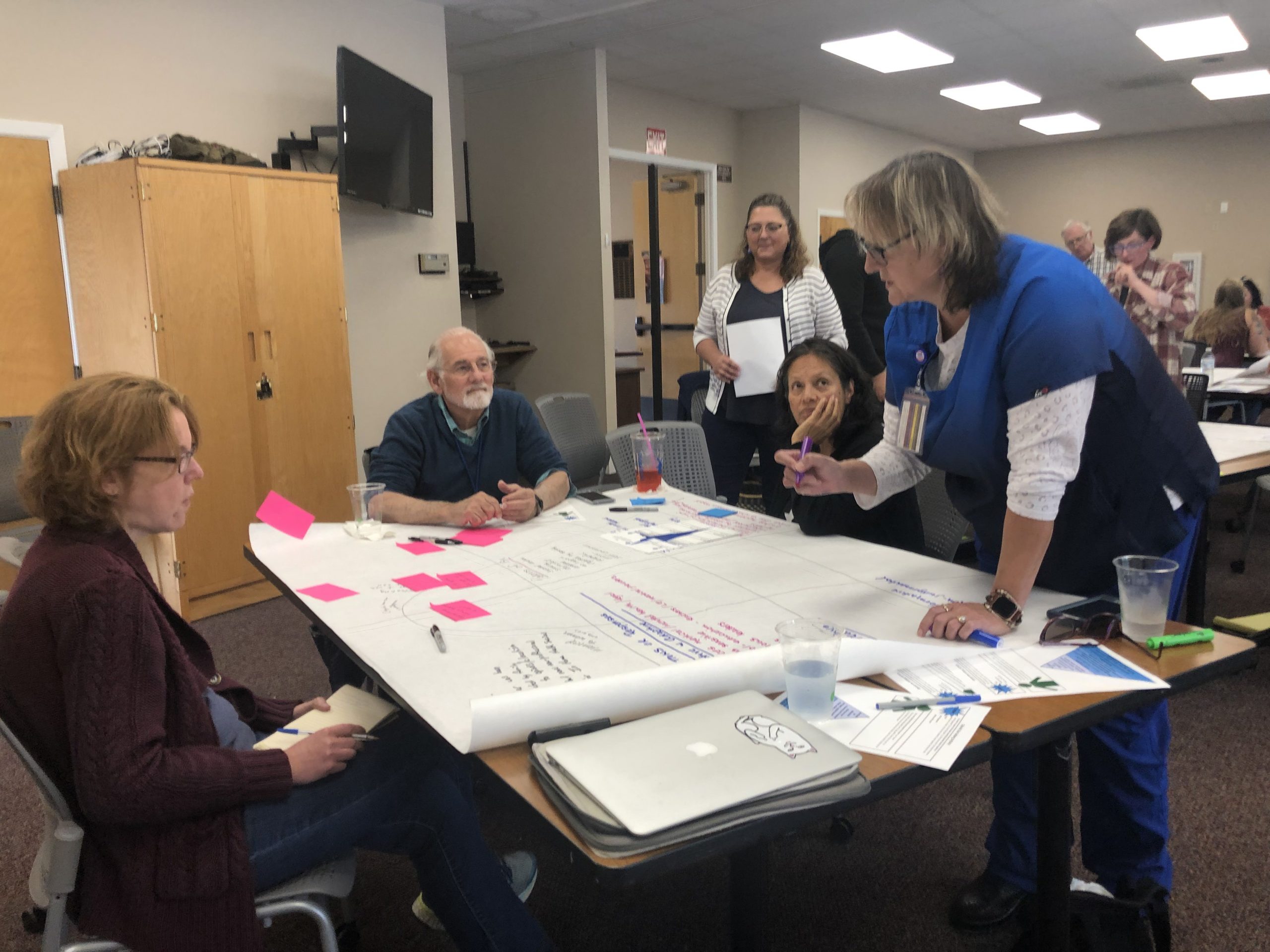

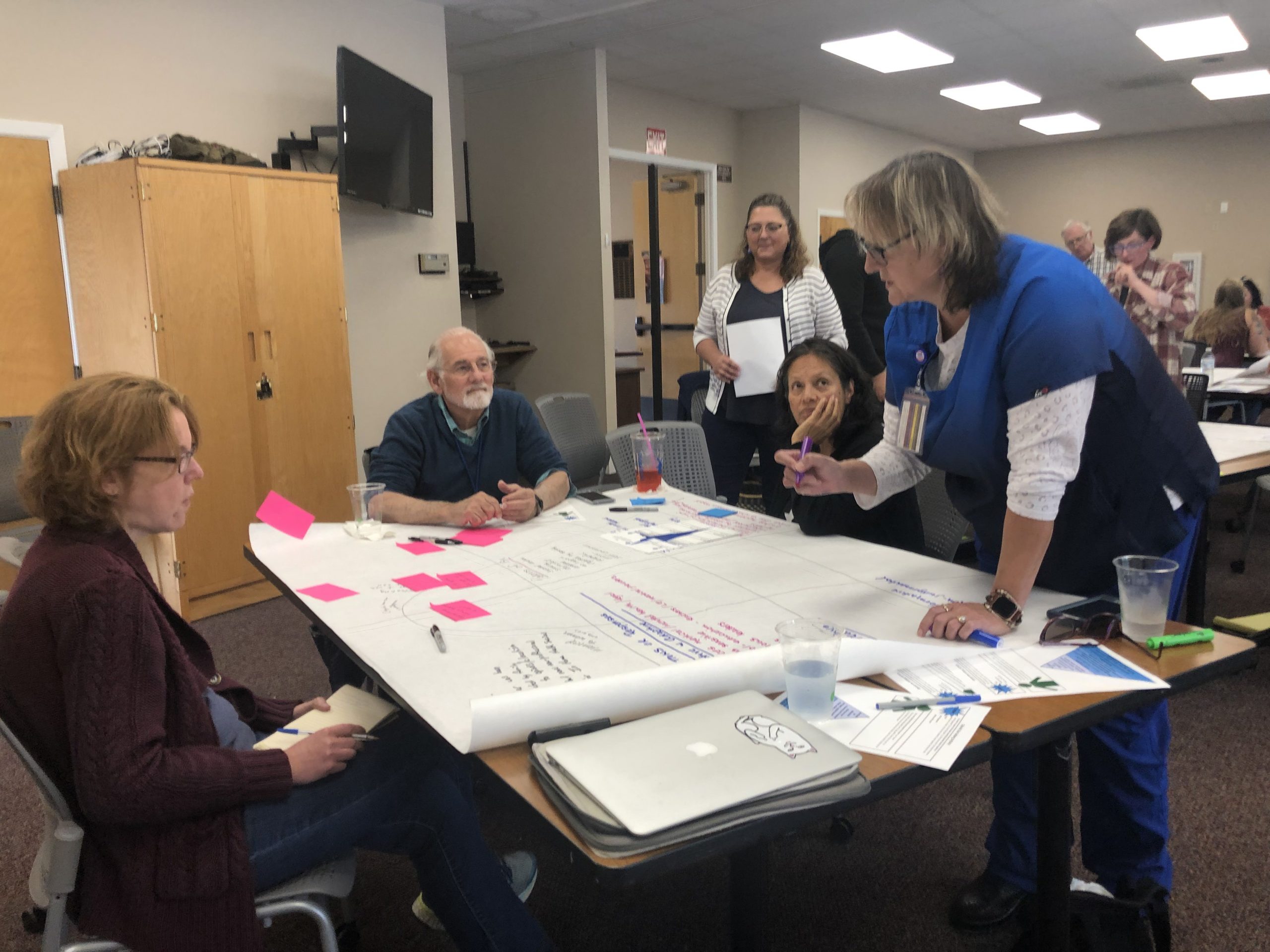

Prior to the pandemic, the group also held six in-person workshops to better understand the complexities of substance use disorder in the community and to brainstorm actions to address this systemic problem. Meetings were conducted with around 10 to 60 stakeholders, including first responders, residents with lived experience, and groups involved in medications for addiction treatment, which is known by the acronym MAT in the substance disorder community. This combination of prescription drugs with psychological and behavioral therapy is one approach to address and manage rampant morbidity and mortality associated with opioid addiction. Studies have shown that medications for addiction treatment (typically methadone, buprenorphine, or naloxone) reduce the risk of overdose deaths by 50 percent and increases a person’s time in treatment, according to a first-person account in Kaiser Health News.

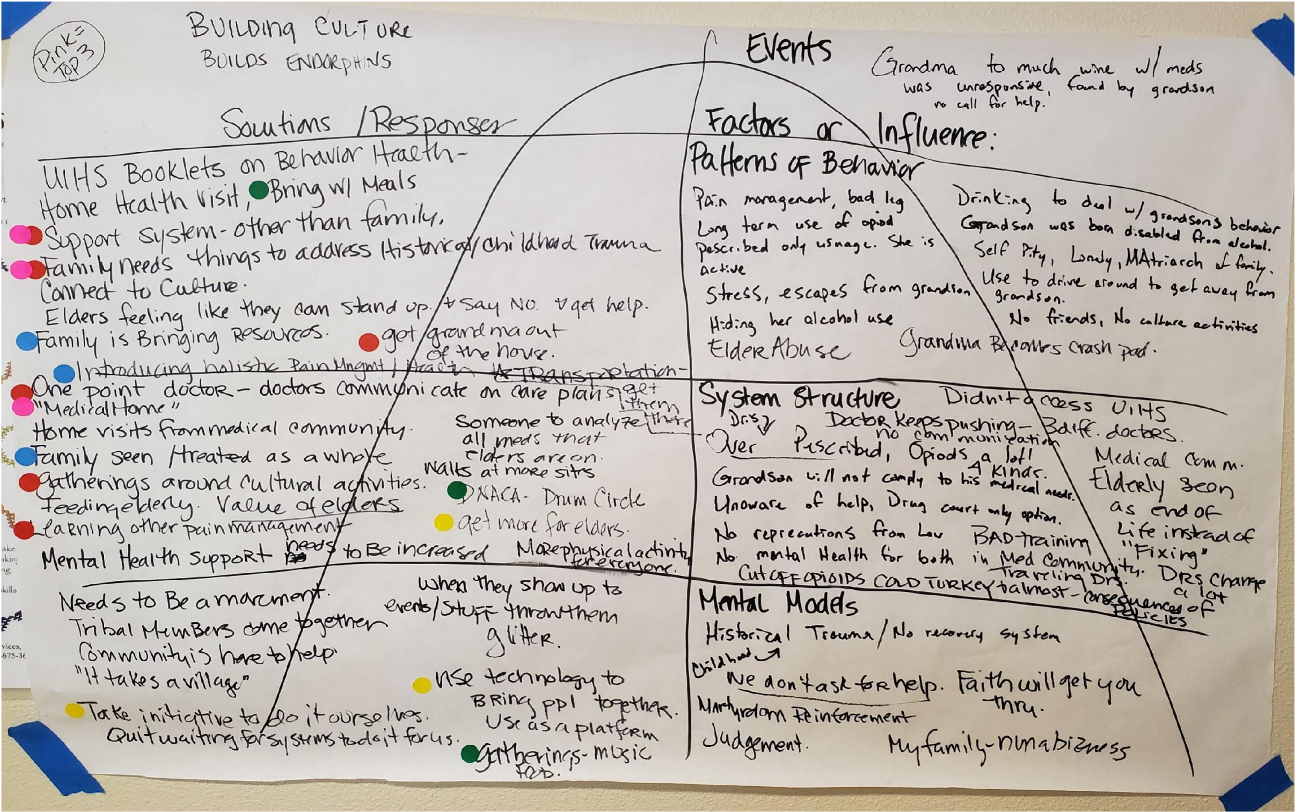

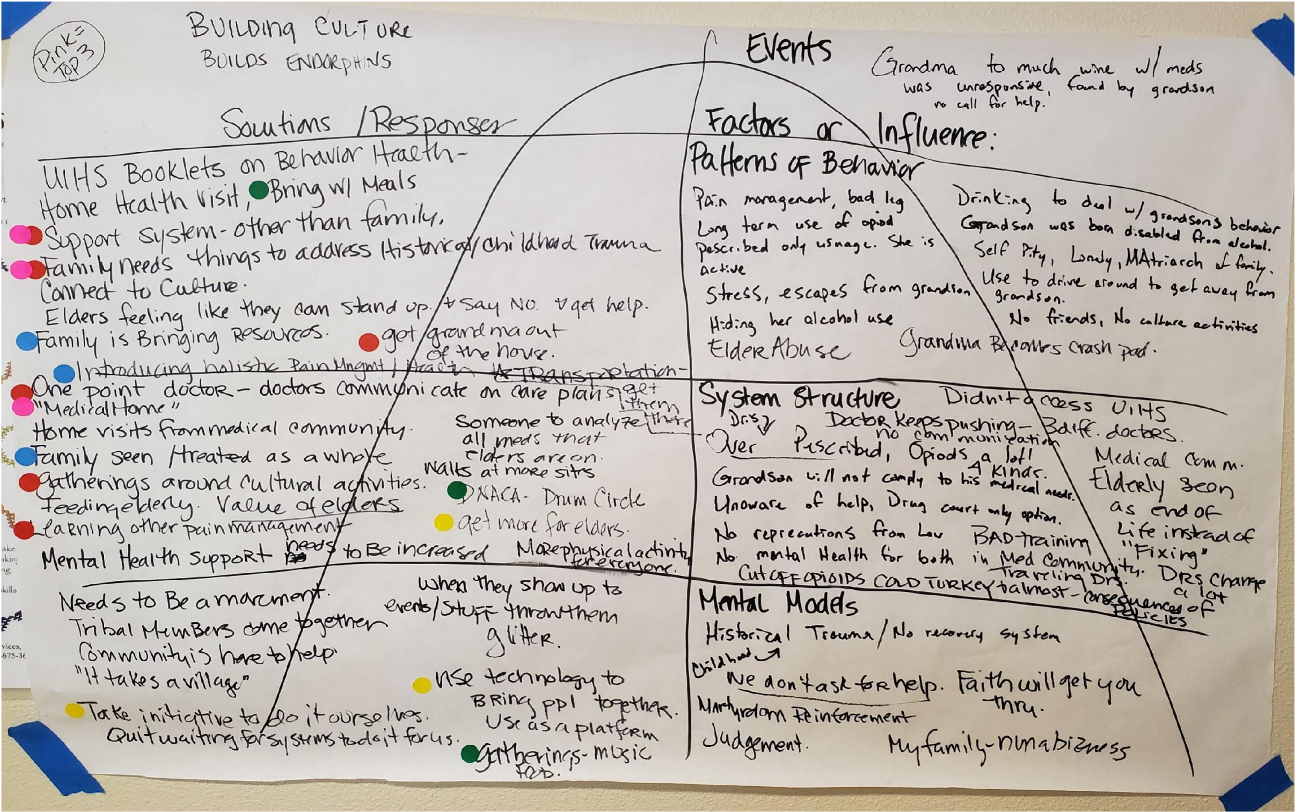

At these interactive workshops participants took part in a relatively new exercise known as iceberg mapping. This visual systems thinking tool is designed to help facilitate change around complex, multi-system problems. Iceberg mapping helps an individual or group discover patterns of behavior, supporting structures, and mental models that underlie a particularly vexing, multi-level concern, with an end-goal of looking for solution pathways. “When systems are siloed we compete for funding and resources in a very small community and that can create barriers to care,” notes Brubaker. “We are always struggling to braid these things together and improve access.” Another important benefit of the systems mapping exercise: all stakeholders “felt seen and heard by the process,” according to Brubaker.

While their online COVID-19 workarounds were well received, Brubaker acknowledges they still had challenges reaching Native Americans in areas such as Klamath, where access to technology and Wi-Fi is challenging. And they struggled with connecting with residents in recovery whose housing situations may not have stabilized. But given the obstacles the pandemic posed for their project goals, they were pleased with the audiences they did reach.

While their online COVID-19 workarounds were well received, Brubaker acknowledges they still had challenges reaching Native Americans in areas such as Klamath, where access to technology and Wi-Fi is challenging. And they struggled with connecting with residents in recovery whose housing situations may not have stabilized. But given the obstacles the pandemic posed for their project goals, they were pleased with the audiences they did reach.

Working Closely with Community Partners

Other key components of the coalition’s work during the CCI collaborative included the completion of the North Coast Resource Hub, an online resource that helps both those in crisis and those in recovery. The guide, funded by the North Coast Health Improvement and Information Network, includes more than 200 resources, from health and treatment options to shelter and clothing sources. The plan is to maintain and update the database and, in partnership with the information network, help to grow and fund the resource hub.

During the collaborative, Rx Safe Del Norte offered online tutorial trainings for administering naloxone, which can block the effects of an opioid overdose. Using funds from the California Department of Public Health, the coalition created more than 350 kits with two doses of naloxone and provided no-contact, pandemic drops for trained first responders and community members in Crescent City, Klamath, and Smith River. The coalition partnered with Yurok Tribe Wellness Coalition to ensure naloxone instruction reached the indigenous community. The tribal coalition offered community members a $50 stipend to attend trainings; and the substance use disorder coalition provided the online platform for the training, promoted it on social media, and included it in its wellness and recovery series.

One stated goal of Rx Safe Del Norte: Zero deaths from opioids by 2025. In 2017, there were 4 documented deaths due to opioid use. It’s not clear yet how many overdose deaths are prevented due to naloxone use, but that is something the coalition would like to track beyond emergency department data, which doesn’t account for all the potential overdoses in a community, Brubaker explains.

From the systems mapping work, another goal that emerged was the importance of collaborating with substance use resource navigators, who serve as community liaisons for people in need. “It was so clear how necessary these positions are, there were gaps present in our area and these community-funded positions are helping to fill that void,” says Brubaker, of Department of Health and Human Services resource navigators, who come from medical, mental health, substance use, and counseling backgrounds. “Law enforcement would tell us: ‘We see people in crisis every day, but we aren’t crisis managers. We’re not the right people to sit with these people.’”

In 2020, two substance use resource navigator positions were funded in the community. One is located at Sutter Coast Hospital in Crescent City, the county’s only hospital, and one at an Open Doors Community Health Center, also in Crescent City. “The coalition will help to continue to make sure that those positions are meeting the needs of those with opioid use disorder,” says Brubaker, “that they have access to resources and are working in collaboration.” The positions, Brubaker adds, look completely different than envisioned pre-pandemic, when it was hoped that navigators would work within the community, versus virtually.

But challenging times call for adaptation. “We will look at how those roles are working, what potential barriers and opportunities emerge, and how we can refine this role to lead to a more robust ‘no wrong door’ community,” Brubaker says. A “no wrong door” approach is a guiding principle for providers to ensure that all individuals presenting for help are given appropriate treatment services (or referrals, if needed), regardless of where they enter the system. “We are able to leverage the work we have done to help make these roles more robust and better connected,” she says, “DHHS and Open Door have used our YouTube library to train their case managers.”

Reaching Community Stakeholders

One of the outcomes from the collaborative workshops: A chance to form new relationships, including with law enforcement and elected officials. Those partnerships are vital, says Brubaker, to bring about important change in approaches and policies to treating drug addiction in the community.

For instance, at the start of the project, Brubaker thought introducing medications for addiction treatment in jails would be a straightforward addition in the county. That ended up being a tougher nut to crack and required substantial relationship building and education of medical staff in jails. “We thought we would knock out MAT in jails early on in this process, but it’s proven a hard, complex problem to tackle and we’re still building those relationships,” she explains. “It’s a work in progress: We take a couple of steps forward and a couple of steps back.” Still, Brubaker’s confident that such programming, which is becoming more common in incarcerated communities around the state, will find its way into Del Norte County jails, too. The wellness and recovery series, she says, was a good ice breaker to get the local sheriff’s department publicly on board with the MAT program. Medical staff in jail need to understand that MAT is a best practice, says Brubaker, who adds that the coalition needs funding to help move the project forward, and to educate and destigmatize within law enforcement, prosecution, and medical providers within the jail system. “We are starting at square one in a lot of ways.”

Opioid use disorder represents the deadliest drug epidemic in US history. In addition to the devastating effects on the health of individuals, families, and communities, opioid use disorder is also a major driver of high-cost health and medical service utilization, such as inpatient and emergency department care. The epidemic has caused an enormous economic burden on health and other government systems. Brubaker knows this only too well. She recalls hearing from a resident with lived experience who was in and out of jail 13 times because every time she re-entered the community, she ended up back in a housing situation that was not conducive to recovery as she was living with a drug dealer. Connecting community members with substance use disorder to resources — such as half-way houses and women’s shelters–and other support services is crucial, she says, to bring about sustained change.

It’s important to reach out to all system stakeholders to garner their buy-in, says Brubaker. One of the beauties of being in a small community, she adds, is that those kinds of connections aren’t typically tough to make. “We don’t have layers of staff to get to the people in power. You know who these people are and may already have a relationship with them,” she says. “It’s easier to make an appointment with that member of the city council, board of supervisors, or sheriff’s department if you routinely run into them at the grocery store.”

Next Steps

Rx Del Norte is experiencing a financial shortfall which is impeding the organization’s ability to continue aspects of its work. Brubaker says they are currently applying for grants to secure funding for follow-up to its systems mapping findings. That said, she’s proud of what the coalition has accomplished to date. “We hope to continue our work and go deeper with new online content for educational and training purposes, as well as promote what we have online now in our digital archives,” she says. “We will continue to build empathy, break down stigmas, increase access to resources, and reduce the barriers to treatment and recovery.”

Del Norte is home to a significant Native American population, which is both disproportionately impacted by the opioid epidemic and chronically undeserved by health care, notes Brubaker. Native Americans are 50 percent more likely to die of an opioid overdose than non-native people, according to a Washington Post analysis in June 2020. The county’s Native American communities include Elk Valley Rancheria, Resighini Rancheria, Tolowa Dee-Ni’ Nation, and Yurok Reservation, home to the largest federally recognized tribe in the state. Yurok Tribe Health and Human Services, Yurok Tribe Wellness Coalition, United Indian Health Services, and Tolowa Dee-Ni’ Nation Community and Family Services are active in Rx Safe Del Norte, whose fiscal sponsor is Open Door Community Health Centers. RxSafe Del Norte holds meetings at Open Door’s Crescent City clinic location.

Del Norte is home to a significant Native American population, which is both disproportionately impacted by the opioid epidemic and chronically undeserved by health care, notes Brubaker. Native Americans are 50 percent more likely to die of an opioid overdose than non-native people, according to a Washington Post analysis in June 2020. The county’s Native American communities include Elk Valley Rancheria, Resighini Rancheria, Tolowa Dee-Ni’ Nation, and Yurok Reservation, home to the largest federally recognized tribe in the state. Yurok Tribe Health and Human Services, Yurok Tribe Wellness Coalition, United Indian Health Services, and Tolowa Dee-Ni’ Nation Community and Family Services are active in Rx Safe Del Norte, whose fiscal sponsor is Open Door Community Health Centers. RxSafe Del Norte holds meetings at Open Door’s Crescent City clinic location.