As the COVID-19 virus enveloped Northern California, community health clinics in two of San Francisco’s poorest neighborhoods were faced with an urgent challenge: How could they equalize the playing field and get people in their communities vaccinated when the city’s public health systems were struggling with limited resources?

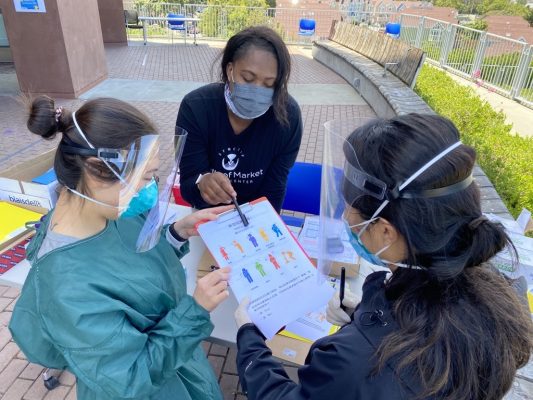

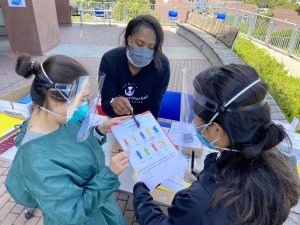

South of Market Health Center medical team reviews testing intake forms during a COVID-19 testing event (Credit: SMHC)

Enter the South of Market Health Center (SMHC), one of the first community health clinics in San Francisco and one that was created in direct response to the inner city’s lack of access to health care to the poor and medically underserved.

For almost 50 years, SMHC has operated on the principle that healthcare is a right of every citizen and has a mission to increase access to care, regardless of the individual’s cultural, social, or economic circumstances. Dr. Asa Satariano, CEO of South of Market Health Center, and her executive leadership team realized that they had to do things differently if they were going to save more lives in their vulnerable communities.

To start with, the unequal vaccination rates among low-income people of color and wealthier, whiter communities were compounded by huge inequities in the rates of infection by the coronavirus.

In San Francisco, Latinos had a far higher infection rate than whites, comprising 25% of COVID-19 infections while making up only 15 percent of the population. In the Mission District alone, which had the highest number of COVID-19 infections in the city, Latinos made up 95% of those infected. In Bayview Hunters Point, 18% of the neighborhood in one census tract had developed COVID-19, compared to a tract in the city’s Noe Valley neighborhood, where only 1.6% reported infections – meaning the Bayview census tract’s confirmed infection rate was more than 10 times higher. “If the [Bayview] tract were its own county, it would have the worst share of cases of any urban region in the country,” the San Francisco Chronicle declared.

Meanwhile, Asians in the City comprised 46% of all coronavirus deaths, despite making up only 34% of the population. Likewise, Blacks in San Francisco County – as well as Alameda and Santa Clara Counties – died of COVID-19 at twice the rate as every other race, according to the California Department of Public Health.

Zeke Montejano and PNPs Ali Rodriguez and Simone Ippoliti at a COVID-19 testing and vaccine event

These statistics were all too familiar to Simone Ippoliti, site director of the Bayview Child Health Center, a clinic of South of Market Health Center, who was working with patients in Bayview-Hunters Point, one of the poorest neighborhoods in San Francisco. “It was almost surreal to be in the city during the pandemic, where a lot of tech employees were glad to be working from home and being with their families,” she said, “because for months on end, a week didn’t pass without us being on the phone with one of our families in which a loved one had either been hospitalized or died from COVID.” It felt almost as if the rest of the city was busy baking homemade bread and hiking while her neighborhood was locked down and grieving.

Ippoliti is a pediatric nurse practitioner, working in a health center that serves the historically Black community of Bayview-Hunters Point, which is home to tens of thousands of African Americans, Latinos, Asians, whites, and immigrants from around the world. She and her staff work closely with Zeke Montejano, the director of clinic operations at the South of Market Health Center, whose clientele includes both displaced Californians and thousands of day laborers and families from Mexico, Central America, Asia, and other places in a SOMA neighborhood overflowing with tech startups.

Barriers to access

The Bayview has long been a vibrant part of the city, but with only one unreliable light rail line to downtown San Francisco and back, transportation is a problem. Both Ippoliti and Montejano were thrilled as California began distributing the vaccine, but they also noticed some red flags. Trying to reach the most vulnerable, the city had opened two mass vaccinations centers in its lower southeast quadrant running from Chinatown and the Tenderloin down to the Mission and Bayview-Hunters Point. However, Ippoliti noted that many people who wanted the vaccine did not have access to public transportation to get to the closest mass vaccination site, while some homebound people remained unvaccinated because they could not take mass transit at all. “Even those who qualified for the vaccine had a very hard time getting it,” she said.

If their patients were going to achieve herd immunity against the coronavirus, she and Montejano reasoned, vaccine distribution had to be more equitable. The question was, how could two small clinics achieve vaccine equity when giant health systems nationwide had faltered?

South of Market Medical team doing intake

The answer lay in part with the strong relationship the clinics were building with their clients and community-based organizations, an approach that holds important lessons for other clinics and health systems trying to distribute vaccines to other underserved communities. “It starts with community trust and human connection,” said Ippoliti. While large healthcare organizations can seem distant and disconnected, her clinic is literally part of the neighborhood. “People want to see service providers that feel like part of their community, that don’t look like they’re part of a massive institution or part of the government,” she said. “It helps for us to be right here on Third Street in the Bayview, actually right down the road.”

In their race to inoculate their patients against the coronavirus, the two clinics together provided nearly 10,000 COVID-19 vaccines. Unlike some health centers who had trouble reaching low-income residents and people of color, “we had folks lining up outside our doors at one o’clock to three o’clock in the morning, they were so anxious to get vaccinated,” Ippoliti recalled. By March 23 of this year, when the priority was still vaccinating people 65 and older, healthcare and education workers, the Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood alone had vaccinated 36% of its residents – a rate over baseline higher than almost all other neighborhoods in the city. As the San Francisco Chronicle reported, “The Bayview… has one of the lowest median household incomes in the city, at just over $65,000, yet is one of the neighborhoods furthest ahead in vaccinating residents beyond the high-priority baseline.”

Ippoliti and Montejano recalled how moving it was to be able to vaccinate elders in assisted-living homes, who were ecstatic at the chance to see their grandchildren and families for the first time in over a year. “The vaccination was a moment of joy that they would be able to be reunited during this worst of times, in which so many people had died without being able to have their loved ones beside them,” said Ippoliti.

She remembers in particular an immune-compromised patient she was able to vaccinate, “and her mom was just over the moon – she had been hunting for a provider to vaccinate her for so long.” Montejano also encountered a 42-year-old woman starting chemo who had reached out to all the providers she knew for the COVID vaccine, without success. After Ippoliti vaccinated her, the woman wept with relief.

“Not throwing away my shot”

How was South of Market Health Center able to get such relatively high vaccination numbers? On a recent Zoom call, Ippoliti and Montejano talked about their thoughts on why their clinics were able to get such high vaccination rates – and what other clinics might do to get more patients vaccinated:

1. Locate clinics and vaccination fairs in the neighborhoods you serve

One advantage the clinics had over large, better-funded healthcare organizations is that they weren’t part of the larger system that had bred so much distrust. “Some individuals would ask me at vaccination sites, ‘Are you from the government?’” Montejano recalls. “We replied that we were not.” And it was just so clear to us that if we were, there would be no trust. Sometimes community clinics have to do something and rebrand themselves to gain the trust of the community.” When people learned that the staff was from the neighborhood community health center, many agreed to get the COVID vaccine.

That was especially important because Black and immigrant communities have strong reasons for distrusting both the government and health care. African Americans have experienced historical racism in the medical system that has left many anxious and suspicious of U.S. healthcare providers. Latinos also report a higher level of distrust of physicians than whites, and the recent surge in abuse of immigrants at the border and child/parent separation has made them even more wary of authorities.

In addition, community members had been barraged for months with false information on the internet and social media. Rumors abounded: The COVID vaccines are unsafe. The vaccines include tracking devices. The vaccines make women sterile. There was talk that a certain vaccine included human fetal tissue, leading to opposition from Catholic churches.

Alarmed by lower-than-expected vaccine numbers, physicians and nurses in nearby Davis and Vacaville, California, released an impassioned remake of Hamilton’s “My Shot” in March of 2021 with the blessing of Lin-Manuel Miranda, that encouraged people to get their shots.

The message was both timely and important. “There was a lot of hesitation we had to overcome, especially because the vaccine had been developed so quickly,” said Montejano. “Our Latino community had significant reservations related to the misinformation they’d heard. They would joke with us, ‘You’re not going to put a tracer on me, right? You’re not going to put a GPS on me?’ And of course, our staff would reassure them and sometimes joke back as they gave them the vaccine” – a type of banter and camaraderie that helped ease the tension.

2. Work with community partners to build up trust

When COVID-19 tests first became available, Bayview Child Health Center teamed up with HOPE SF and the Bayview YMCA during a weekly food pantry distribution to build a coalition of service partners that could meet families where they were at in terms of addressing vaccine concerns – and providing vaccines in spaces they already knew and trusted.

Connecting with an organization with strong local ties helped remove some of the barriers. As months went on, people on the community simply accepted that the health center was the place to go for testing. Later, it became a well-trusted and culturally responsive weekly pop-up testing and vaccination site. “Co-locating those services at the beginning of the pandemic allowed us to build that trusting relationship,” Ippoliti said. “We had the same team coming to do tests or vaccinations every time, so people would get to know us,” said Ippoliti. “And after a while, they began asking for us by name.”

South of Market Health Center has built many other connections before and during the pandemic. It worked with the Central City SRO Collaborative based in the Tenderloin district, which helps organize tenants in the city’s single room hotels. They have also partnered with the local YMCA for the COVID-19 vaccination drive and food distribution, as well as after-school programs, Conard House, HOPE SF (the cross sector public housing initiative), the Samoan Community Development Center, FACES SF, and other neighborhood groups. To further expand their reach, they so worked closely with Chinese and Vietnamese interpreters from the city’s Department of Health Services.

“COVID-19 shifted the center’s thinking about trauma and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) on a community level,” said Leena Singh, DrPH, about the South of Market Health Center, which is a participant in CCI’s Resilient Beginnings Network. A coach and advisor for RBN’s health care participants, Singh explains that the South of Market Health Center and its Bayview Child Health Center were early pioneers of ACEs screening, “so they have taken what they know about this field and funneled it into supporting the community in this latest community trauma. Their approach has been to think about this work through the lens of trauma that patients go through, deal with misinformation and shift decisions to the community.”

3. Keep communication thoughtful and consistent

The mission to deliver vaccines to underserved communities was hampered by a lack of vaccines available at the national level, Ippoliti said. In her view, a lot of nationwide efforts around vaccine equity were “patchwork, ad hoc, and inconsistent across the board.” Mused Ippoliti: “I don’t think the CDC and other health organizations did the best job of educating our communities as to why vaccination was so important. They took that approach sort of late in the game, and I completely understand because we had just had a change of administration. But with the lack of information came a lack of confidence, even among our providers.”

4. Be open and transparent on immigration issueS

Patients prepare to get vaccinated during a South of Market Health Center Saturday clinic (Credit: Maggie Hallanan)

Fear of immigration services proved to be another major obstacle to vaccinations. “Undocumented immigrants worried they could not access government services if they were pursuing a visa or if they were here on asylum,” said Montejano.

Specifically, people who were trying to get documented feared that they could ruin their chances by accessing services. “We let people know that we do not need anything other than a name and date of birth to get vaccinated – any form of ID was accepted,” Montejano said. “And that you do not need anything for us to test you. We went through extensive measures to make things feel as transparent as possible so patients would trust that what we were doing was not going to affect them.”

5. Make house calls and push for the ability to use your own judgement

If you can’t bring all the community members to vaccination sites, why not take the vaccines directly to them?

“Even though we’re a pediatric clinic in Bayview, we did a lot of house calls for elderly individuals who were home-bound, because those were the people who needed vaccines the most,” Ippoliti says. The clinic was able to stay nimble because it had the latitude to make its own decisions without interference from a large bureaucracy, she says. “We had the latitude to make executive calls during the pandemic that felt more patient-centered than usual, and that made a big difference.”

6. Encourage cities to prepare for quarantine AND SELF-Isolation

Ippoliti was struck by the irony of San Francisco’s status as a poster child for pandemic response. “I think there’s a real narrative in San Francisco about how well the city is doing, and that COVID really wasn’t an issue here, but that just wasn’t the reality of families in the Bayview,” she said. “Community members are almost exclusively frontline workers, so they were Uber drivers, they were working in grocery stores or day care. COVID had profound social, financial, emotional, and physical ramifications for our families. It bred a lot of isolation, anxiety, and stress about financial survival. And because we have a lot of multigenerational homes where an entire family rents each bedroom, there was no isolating or quarantining, nowhere for people to go. They had come to accept that they were going to give their loved ones COVID.”

The city scrambled to negotiate for hotel rooms where people could quarantine, but it was too little, too late. With only one psychologist at the Bayview clinic, the providers faced a tsunami of medical and social crises. “Even if we had had partner agencies in place, the mental health burden from COVID was enormous,” said Ippoliti. “I was seeing kids, and their chief complaints were depression, suicidality, and anxiety. The resources did not even remotely meet the demand.” Worse yet, those lucky enough to be connected to therapy often did not have confidential spaces in their homes to speak to counselors via telehealth.

7. Cherish your relationships

“Lean on me/when you’re not strong

I’ll be your friend/I’ll help you carry on…”

— Bill Withers

The pandemic took a heavy toll on healthcare workers, and Ippoliti and Montejano were no exception. “Burnout, obviously, is at the top of my list, along with depression and anxiety,” said Montejano. “That’s just like our patients. I could tell you that if it were not for my immediate circle of family friends – because I have no family in northern California; all my siblings and parents live in southern California – I would be a wreck. So, it was nice to continue having relationships in a safe way.”

South of Market Health Center team at the inaugural COVID-19 testing pop-up event in May 2020

Ippoliti agreed. “In this very warped way, you and your coworkers sort of become a family,” she said. “It was really just four to six of us, running these events to provide testing and vaccines for the entirety of the Bayview. And while Zeke Montejano is based out of the South of Market Health Center, he was so critical to any testing and vaccination efforts that were done in the Bayview. Being able to rely on him and having this shared emotional experience on the front lines of COVID was critical to my mental health. I found that I couldn’t really connect with anyone who wasn’t also doing this work.”

__________________________________________________________________________

The South of Market Health Center is part of the Resilient Beginnings Network, a learning program that promotes trauma- and resilience-informed care so that 100,000 young children and their caregivers in the San Francisco Bay Area have the support they need to be well and thrive. The Resilient Beginnings Network is supported by the Center for Health Innovations, an Oakland-based nonprofit that supports health equity and innovation in the health care safety net, and by Genentech Charitable Giving.

Find this useful or interesting? We’re constantly sharing stuff like this. Sign up to receive our newsletter to stay in the loop.