Six health care safety net organizations have spent the past 18 months testing, refining, and implementing innovations to help combat food insecurity in their communities. Despite embarking on this work under unprecedented duress in the middle of a global pandemic, they still managed to strengthen and expand their capabilities and infrastructure to assess and address this crucial social determinant of health.

Below, these Los Angeles-based, federally qualified health centers (FQHCS), part of CCI’s Moving Clinics Upstream (MCU) program, share detailed, practical suggestions for tackling this challenging problem, whether an organization is just starting out, expanding its work, or introducing change during a healthcare crisis.

1. Pivot Quickly In The Face of a Pandemic

Beginning in March 2020, all six clinics moved quickly and successfully to address the unique obstacles the coronavirus unleashed. Each organization shifted from in-person clinic visits to telehealth services to connect with clients during the pandemic. Virtual visits became the norm as the lockdown months wore on.

Each clinic also found creative, collaborative solutions to delivering food services to patients in need, as demand soared during COVID-19 shutdowns and widespread unemployment.

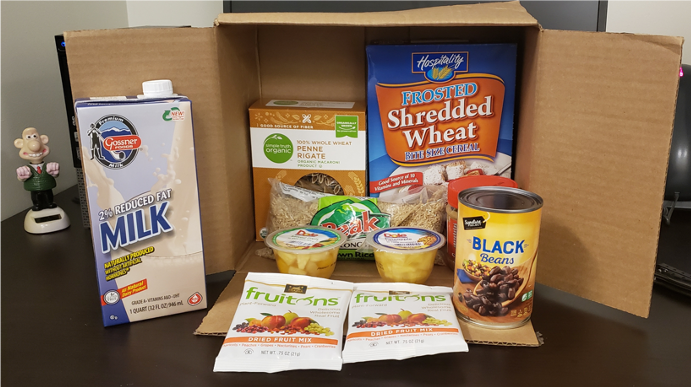

Behavioral Health Services began sending Wholesome Wave grocery gift cards to clients in the mail. Eisner Health referred patients to pandemic-response feeding programs, such as Los Angeles Unified School District Grab n Go Centers. St. John’s Well Child & Family Center strengthened community ties with organizations such as APAIT, TransLatin@ Coalition, and Los Angeles Regional Food Bank to connect clients to emergency food supplies. APLA Health moved its well-established food pantry into a parking lot to help facilitate social distancing and create a safe and efficient distribution hub. Groceries were pre-bagged, versus farmers market-style selection, and essential supplies and personal protective equipment was included in the mix. Alta Med Health Services Corporation and Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles (CHLA) partnered with Imperfect Foods to deliver food boxes to food insecure clients at home. The Los Angeles LGBT Center launched its Pride Pantry, a direct response to the rapid increase in need for food assistance brought on by the pandemic.

2. Start With Screening

All six clinics now screen patients for food insecurity, using the Hunger Vital Sign, a simple screening tool developed by the Nutrition and Obesity Network.

Lessons learned along the path to screening clients:

- Normalize social screenings with the goal of screening all patients. That said, a pilot program and roll out strategy may work well to address any workflow issues. Clinics might consider starting with a particular site location, care team, or group of patients enrolled in an existing program.

- Identify a screening program champion within the organization. Many screening programs are understaffed, which can result in inconsistent screening and poor follow up on identified needs, notes a social screening guide compiled by MCU coaching collaborators Elevation Health Partners. Staff conducting food insecurity assessments are often not the same staff as those addressing patient needs. A program champion can ensure internal best practices so staff best placed to support screening work (including case managers, care coordinators, medical assistants, nurses, patient navigators, primary care physicians, and outreach coordinators) are engaged and informed about their role to address this concern.

- Select a screening tool, assess a clinic’s information technology, and embed the questionnaire in the clinic’s electronic health record intake process.

- Develop an accountability plan and design workflows to capture data metrics and follow up. Outline staff roles and responsibilities: Who asks the questions? Where are the responses documented? How are the provider and care manager flagged when a patient screens positive? How is follow up documented, tracked, and reported?

- Note that virtual screening can have a distancing effect. To counter this potential impact ask permission, screen everyone, and employ empathy: there is still stigma and shame associated with food insecurity for many clients.

3. Secure Buy-In At All Levels of the Organization

It’s important to include everyone—administrative staff, nurses, medical assistants, social workers, physicians, IT team, drivers, volunteers, accounting, operations, marketing, and management—in this process. The engagement, input, and feedback of all stakeholders are a prerequisite for success.

When there is strong leadership support, commitment, and organizational buy-in, the main challenge becomes how to do something not with whom. Frontline staff are often the leaders and champions of this work. It takes a village.

Committed leadership understands a program’s budget and staffing needs, technical issues, reporting mandates, and operational concerns, and leadership works together with care teams to address barriers, develop community resources, and streamline services. Leadership shows commitment by showing up, engaging in process and progress, and demonstrating support through actions, and as our coaches at Elevation Health Partners and MCU participants note, is key to long-term success. Getting that buy-in in writing early in the process can help set the tone for this kind of programming.

“Food security is the tenet and the foundation for a child to grow in a healthy way,” notes pediatrician Mona Patel, vice president of ambulatory operations at CHLA, and a staunch advocate for food insecurity screening at clinics. “Food insecurity is challenging because you don’t want judgement, and it can be a hard one for people to acknowledge they are struggling,” she adds. “Food insecurity screening is important because of how foundational access to nutritious food resources is and how critical that is to a child’s outcomes for the future.”

4. Listen to Patient Stories

View this post on Instagram

By truly listening to patients and hearing their stories, clients learn to build connections through patient navigators, case workers, front office staff, and clinic practitioners. Even without formal data, this anecdotal information gathering helps to uncover what patients really need and how they might best be served.

Take time to understand people’s personal narratives. Public health data, client surveys, and patient questionnaires are helpful guides. But the real experts are clients. Ask patients: How can we help? What do you need to live a healthier life? What is preventing you from achieving that goal? This kind of check in can help with patient retention, increased trust, and patient engagement in the clinic and its related services. These kinds of check ins with clients are important throughout the process: from screening, referral to resources and case workers, and in regular follow-up conversations. Food insecurity can be short-term and situational. It can also be a chronic, long-term challenge for some clients.

“Screening for food insecurity shows that AltaMed not only cares for the physical well-being for the patient and their families, but also the general well-being of all their patients,” according to one mother of five in South Central Los Angeles, who is an AltaMed patient. “Having a case manager who calls after the appointment to give the resources and a gift card that can be used for groceries is so valuable. This is money that we didn’t have before that can help our family.”

5. Embrace Virtual Delivery of Services

Technology proved key to supporting patients during social distance protocols. For example, APLA Health moved its weekly nutrition education classes online during the pandemic. There were some hiccups initially (the organization opted to use Ring Central as its online provider) and the clinic will likely transition back to live classes soon, but the shift allowed this important component of APLA’s necessities of life program to continue during mandatory isolation. Los Angeles LGBT Center used computer tablets to assist clients applying for CalFresh while also maintaining social distance. St. John’s Well Child & Family Center used whatever technology tools were immediately available to connect with patients, including telephones and social media platforms such as WhatsApp and FaceTime.

6. Collaborate Within The Organization to Share the Workload

Identify resources, knowledge, skill sets, connections, and experience that already exists within an organization to help with this work. Case in point: LA LGBT Center’s Pride Pantry is managed by Dina Valenzuela, administrative and events coordinator in the center’s culinary arts department. Managing a food pantry has many moving parts: ordering food, receiving deliveries, organizing inventory, working with volunteers, coordinating sign ups, and keeping the designated space food safe and up to health code — including meeting COVID-19 prevention protocols. Share the workload across departments, Valenzuela recommends, drawing on expertise within your organization. For instance, facilities staff at LA LGBT Center have experience handling logistical matters. “They assist in receiving all onsite food deliveries, work with the volunteers to pack all the food items, and manage the physical distribution for the pantry,” explains Valenzuela.

7. Seek Outside Partners

Organizations need help to do this work. Court potential partners. Get to know their mission, values, and goals to assess how these align with your organization’s needs and the needs of your clients. AltaMed and CHLA found a good fit with Imperfect Foods, a grocery delivery service that aims to reduce food waste. During the pandemic, the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services contracted with the global charitable feeding program World Central Kitchen to make pre-cooked meals available to vulnerable clients that LA LGBT Center staff delivered to clients’ doors.

Grocery stores may work with clinics on gift card programs and provide surplus items for food pantries. Corporate giving programs can direct food supplies to clinic pantries. Volunteers can play an important, on-going role in food pantry and food distribution work. At APLA Health, for instance, volunteers help pre-bag groceries for clients and are an integral part of the pantry program.

Seek out partnerships to source food. Think food banks, local food producers, community food recovery efforts, non-profit food relief organizations, and corporate giving programs. For decades, Project Angel Food has teamed up with APLA Health to provide home delivered medically tailored meals for people with HIV. In the summer of 2020, that collaboration grew to include a food pantry distribution site at a Project Angel Food location.

8. Iterate, iterate, iterate.

It’s okay not to get it exactly right on the first try. Introducing innovations requires adjusting to meet patient needs and expectations; gathering information from patients, clinic staff, partners, and volunteers; and reconfiguring workflows, processes, and programs. Teams should expect to respond to client and staff feedback about an innovation’s usefulness, convenience, and sustainability. It’s important to solicit insights from all stakeholders. For instance, initially APLA Health had clients come to the clinic’s loading dock to receive food supplies. But it quickly became apparent that the parking lot was better suited to serve as a food distribution site. This was a simple fix that made a big difference to the pantry’s efficiency, with patients more easily able to pick up pantry supplies and go.

9. Meet Clients Where They’re At

It’s essential to adapt programs to match the needs of patients. For example, APLA Health has long provided food assistance to its clients. During the pandemic, the organization realized that they could better serve a particular population: those who don’t have access to a kitchen or cooking facilities. So the organization’s nutrition team developed a bag of no-cooking-necessary groceries. “This was a missed population for us but we’ve since found a way to put together a menu of items that don’t require refrigeration or a stove,” says Jeff Bailey, director of HIV access and community-based services at APLA Health.

10. Strive for Financial Sustainability

Out of necessity, clinics are creative about financing these kinds of upstream activities. Traditional federal sources, nonprofit grants, individual donors, internal funding streams, and outside partnerships—there is more than one way to find funding for innovation.

It’s true, there’s no magic bullet here—no one, steady, stable, sustainable way to support this work in the months and years to come. Many safety net organizations rely on a diverse stream of funding sources to sustain staff positions and food programs to continue this important work. Some funds are specifically earmarked for direct food services, whereas other funding may have more flexible spending mandates, allowing clinics to use the funds for, say, infrastructure or staffing related to an on-site food pantry program.

While APLA Health receives substantial funding from the federally funded Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, Bailey notes that there are other national initiatives that federally qualified health centers can apply for. For instance, he points to FEMA’s Emergency Food and Shelter Program as a potential source of support. In March this year, FEMA announced an additional $400 million in funds for social service organizations feeding hungry and homeless populations as part of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.

APLA Health’s Vance North Necessities of Life Program has a long history of community support in gifts both large and small. More than 50 percent of pantry items distributed to clients come from food drives and donations from supermarket partners. The program has also been able to expand greatly due to the generosity of a community philanthropist: In 2011, Bob North and his wife, Lois, donated $3.5 million to the Necessities of Life Program in memory of their son, Vance, who died of AIDS-related complications.

Elevation Health Partners’ Deena Pourshaban points to the forthcoming California Department of Health Services CalAIM program as a potential source of reimbursement, and she notes that local health plan benefits programs, such as L.A. Care Health Plan, are a possible outlet for funding through community grants.

11. Connect Transport With Food Services

Often food insecurity and transportation insecurity go hand in hand. Keep in mind that hauling grocery bags on public transit may be too much to ask of clients in ill health, or with mobility challenges, or those with young children in tow. And during the pandemic, of course, many people avoided public transit as much as possible. For clients with mobility issues or those who lack convenient access to transit, APLA Health offers transportation via ride share services such as Uber and Lyft. LyftUp offers discounted Lyft car rides to low-income families and seniors heading to and from grocery stores, farmers markets, food pantries, and SNAP (CalFresh) benefits appointments. Uber Connect allows for the delivery of packages such as grocery bags to people’s homes. Uber Health allows providers to directly arrange transport for patients, as does a similar program at Lyft.

12. Celebrate the Small Victories

Responding to food insecurity can feel overwhelming; the need can be urgent, acute, and/or chronic. Think about starting small and growing steady and slowly.

Create an environment that starts with screening for social needs, then build interventions and link patients to resources. It’s important to understand if the changes work well for both patients and staff before spreading them clinic-wide.

Perhaps begin with a pilot project with a particular high-risk cohort or clinic, which can help a health center figure out the kinks in the system, program, and delivery. As one participant from Behavorial Health Services notes: “Know what you have the capacity to do and start from there. Don’t try to progress too fast without building the foundation first.”

Keep in mind that every patient that you serve, support, and connect to services is a success.

13. Keep Pandemic Changes For The Long Haul

After this unprecedented year, many safety net clinics were able to respond to a dramatic upswing in food insecurity. It’s clear that clinics will have an on-going role in ensuring their patients’ hunger needs are met moving forward.

APLA’s Bailey says the health center will likely keep its pantry distribution in the parking lot, because it proved very efficient, with good flow, and frees up indoor space for storage.

Strengthening internal systems for assessing social determinants of health and improving internal workflows has benefits beyond food insecurity, they can be useful in other programs, for instance vaccine rollout. Tweaking best practices around data collection, case management referral, and delivery of services can go a long way to ensuring the viability of such programs. As one MCU participant notes: “Determine what sets you apart from other food programs so as not to duplicate what’s already out there.”

As two of these clinics demonstrate, co-locating food pantry services on site can enhance access and offer one-stop shopping to clients who may be coming in for other services at a health center. As other clinics demonstrate, ensuring that food services reach patients in need—through home delivery, for instance—can eliminate transportation challenges.

As all the clinics can attest, making a commitment to do this work—and having a point person or leadership team that is passionate about meeting this basic human need with compassion, caring, and a capacity for overcoming obstacles while working closely with all community stakeholders—is crucial to continued success to combat food insecurity among clinic clients.